‘I hope they were mates’: The naval legacy Uncle Jack built

The family of one of HMAS Sydney’s lost crew has a special connection to the Unknown Sailor.

Susie Douglas was raised with a picture of the doomed HMAS Sydney on the wall and the shadow of her lost Uncle Jack looming large over her life. What a relief for her that the uncertainty over whether he was the Unknown Sailor – whose remains were all that was ever recovered of the crew of 645 – has finally been laid to rest.

Douglas, 63, a former Gold Coast City councillor, just wishes the identification had come sooner so her dad could have learned who the mystery man was.

If it wasn’t Uncle Jack Primmer, there’s comfort for Douglas and the family in knowing how much he had in common with the Unknown Sailor – who was named as Thomas Welsby Clark of Brisbane on November 19, the 80th anniversary of the disaster.

That galvanising event has rekindled interest in the fate of the Sydney and those who died in the ship after it was ambushed by the disguised German raider Kormoran off the West Australian coast in 1941. The sinking remains Australia’s worst maritime tragedy in war or peace.

Both Clark and Primmer, just turned 19, hailed from the same inner-city suburb of Brisbane, New Farm, and were able seamen whose battle stations were likely close by. Still, they had come from very different sides of the tracks. Clark, 21, was the scion of a wealthy grazing family, an accountant who had attended a well-to-do private school and listed yachting among his pursuits, while Primmer grew up hard in an orphanage with his brother, Conrad, Douglas’s father. He worked on the wharves before joining the navy.

“I am pretty sure they would have known each other because they were both Queensland boys and I’d like to think they were friends,” Douglas says. “There was just so much sadness in the nation, in families like ours when the Sydney disappeared … it was a beautiful ship and represented such hope for Australia. It was like the confidence of the nation was riding on it.”

Imagine how such a loss of life would be received today by a nation nearly four times more populous but with virtually no lived experience of being imperilled by global war. (The median age of World War II veterans is now 93, and their number is diminishing fast.)

As Chief of Navy Michael Noonan says: “There weren’t too many towns or cities in Australia that didn’t have a connection to one or many of the young men serving aboard that ship. At the time, it was a national tragedy of the highest proportions.”

And the sinking of the Sydney was merely the first of a succession of hammer blows to fall. Within days, HMAS Parramatta was at the bottom of the Mediterranean, 138 of its crew killed in a German submarine attack. Closer to home, the dominoes began to topple when the Japanese smashed the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor on December 7. Hong Kong, Manila, then Malaya fell before the supposedly impregnable fortress of Singapore surrendered on February 15, 1942, and more than 15,000 Australian troops marched into the hell of Japanese captivity.

Like many of the Sydney families, Douglas’s was tantalised by the thought of what their lost young men might have made of themselves had they lived.

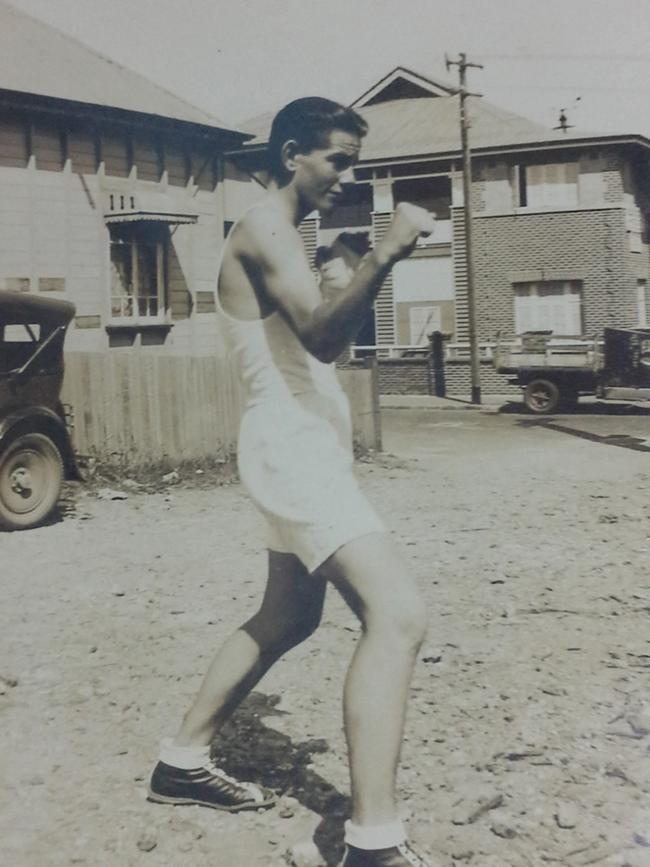

Take her father, Conrad Primmer. He also joined the navy, seeing action in corvettes in the Pacific. Tall and rangy like Jack, he made the most of his opportunities in post-war Australia and played international rugby union for the Wallabies while pursuing a career in medicine.

He became a successful obstetrician-gynaecologist who reared seven children with wife Cecily before he died in 2014, aged 90.

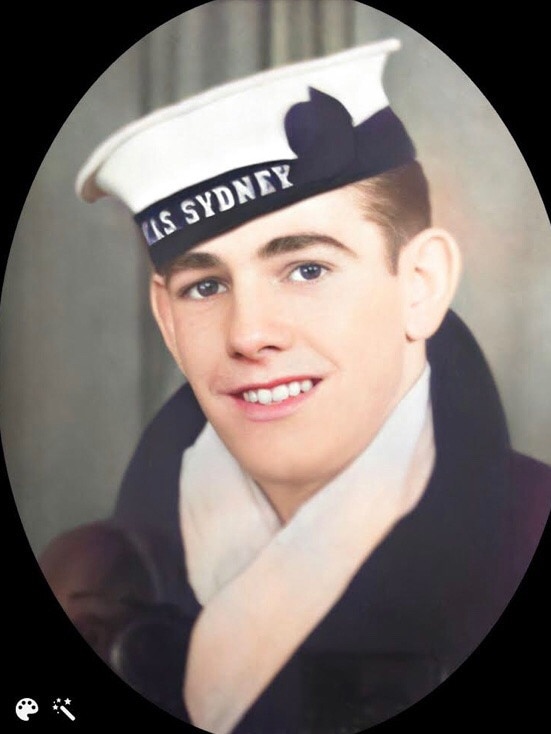

He never got over his big brother’s death or stopped wondering whether Jack could be the Unknown Sailor. The picture of the Sydney took pride of place in the hallway of the family home when Susie was growing up, alongside photos of Jack in uniform and posing, fists poised, as a promising amateur boxer.

“His death was a terrible shock for Dad,” she says. “They were incredibly close and it cast a shadow over him. He found it very hard to grieve and it wasn’t until one of his grandchildren died that he really was able to start that process and grieve for Jack. He had been so young when the Sydney happened. And because of the war, there was no funeral. There was never a closure. So I think the Unknown Sailor, to him, was the one thing he could concentrate on.”

The boys had been placed in care when their parents became destitute during the Depression in the 1930s. Jack left his diary with their mother, Elizabeth, while on leave in the winter of 1941, after the Sydney returned from an action-packed deployment with the British Mediterranean Fleet that made it the pride of the Royal Australian Navy.

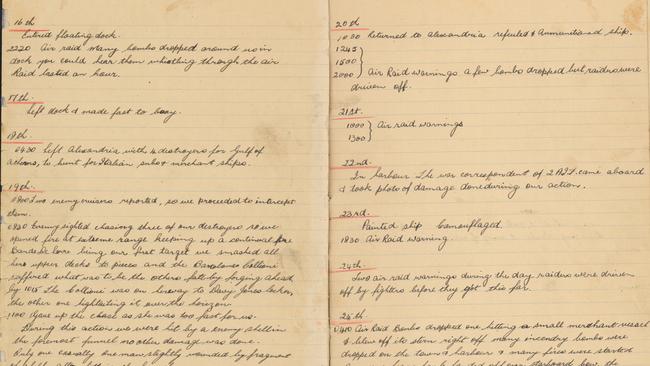

His matter-of-fact prose belies the highs and terrifying lows of war at sea. On July 9, 1940, Sydney “opened fire on a large ship thought to be an 8’’ cruiser, but it turned out to be a battleship … the turrets were now firing very rapidly – we could hear the whine of shells overhead, some bursting quite close to us,” he wrote of a clash with the Italian fleet in which an enemy destroyer was sunk.

On July 19 they engaged the Italian cruiser Bartolomeo Colleoni and an escorting destroyer, Espiro. Soon enough, the cruiser was “on her way to Davy Jones locker, the other one hightailing it, over the horizon”, Jack wrote.

During the action, he noted laconically, the Sydney’s foremost funnel was struck by shellfire: “No other damage was done. Only one casualty. One seaman slightly wounded by fragment of shell after hitting the funnel.”

As other Allied destroyers moved in to rescue a throng of 500-odd Italian survivors, enemy bombers attacked. One of the ships was hit amidships. “We were well ahead and had to turn back and escort her into Alexandria at a very low speed,” he wrote.

Crawling through those deadly waters would surely have worn already-frayed nerves on board the Sydney, but you wouldn’t know if from Jack Primmer’s telling. On the 20th, he recorded: “Returned to Alexandria refuelled and ammunitioned ship … air raid warnings. A few bombs dropped but raiders were driven off.”

En route home on December 31, 1940, he noted that the battle-scarred light cruiser had steamed 21,573km since the outbreak of the war and expended 2769 shells from its six-inch batteries in the Mediterranean. Not one man was killed, a remarkable run of luck that came to a tragic end when Captain Joseph Burnett was duped by the Kormoran into approaching within range of its masked guns.

Douglas says the journal, which her father cherished, was the “wonderful story of a brave young man” who epitomised the sacrifices made by Australia’s World War II generation.

For his part, Clark was posted to the Sydney in August or September 1941 as an ASDIC operator and his battle station was probably off the ship’s bridge, overlooking that of Jack Primmer near B turret.

After their father’s death, Douglas’s sister, Libby Homer, gave a lock of his hair to the RAN for DNA comparison with samples from the Unknown Sailor, whose desiccated remains washed up on Christmas Island 11 weeks after the Sydney disappeared. The location of the grave was lost during the Japanese occupation of the outpost and it was not until 2006 that the site was rediscovered, two years before the wreck of the Sydney was found in 2600m of water. The then Unknown Sailor’s remains were reinterred at the commonwealth war cemetery in Geraldton, WA.

The family would have loved it had it turned out to be Uncle Jack. But putting a name to the Unknown Sailor after all these years was the next best thing.

“He was very much a part of who we are because of the stories Dad told us,” Douglas says.

“We haven’t stopped talking about it since the Unknown Sailor was identified. It has brought it all up again, but in such a happy way. The story is complete.

“They found the ship, they have found the sailor’s identity, and we can all move on. There is no more mystery.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout