How we’re relearning to worry about the bomb

Beijing’s nuclear breakout should dispel any notion that the risk of nuclear Armageddon is long past.

Fear that a conflict between the US and China over Taiwan could go nuclear is shaping the government’s risk assessments, strengthening the case to upgrade our missile defences for critical defence installations and operationally deployed units of the Australian Defence Force.

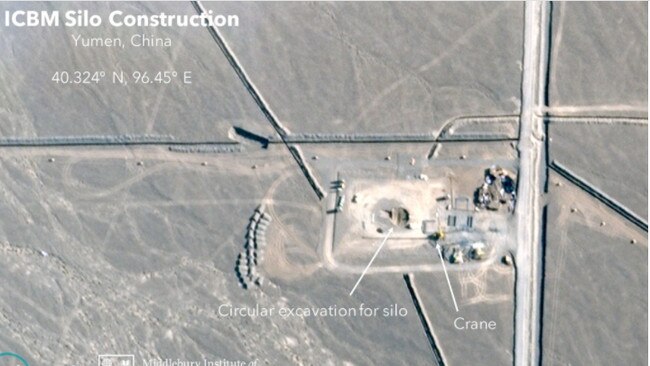

The immediate cause for concern is China’s apparent decision to build as many as 250 new silos for its nuclear-tipped intercontinental ballistic missiles in two remote areas of northwest China near the Mongolian border.

Characterised as a “breathtaking expansion” by the commander of US nuclear forces, Admiral Charles Richard, the construction of these missile silos signals a historic shift in China’s nuclear posture from one of minimum deterrence to a robust capacity to survive an adversary’s first strike and inflict major damage in return.

Although China’s arsenal is still dwarfed by those of the US and Russia, its nuclear breakout could double the number of its nuclear warheads. The expansion is part of a disturbing global trend that reverses the late Cold War momentum towards nuclear arms reductions. There are continuing tensions over North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. Tehran is inching its way towards becoming the 10th nuclear weapons state despite the Biden administration’s efforts to resurrect a nuclear deal abandoned by Donald Trump. And Russian military planners seem to believe it is possible to win a limited nuclear war in what has been dubbed an “escalate to de-escalate strategy”.

As described by former US deputy secretary of defence Bob Work, the Russian strategy “purportedly seeks to de-escalate a conventional conflict through coercive threats, including limited nuclear use”. No one knows if Moscow is bluffing. But the fact Russian forces incorporate nuclear warfighting into their training means adversaries ignore this risk at their peril. A willingness to consider limited use of nuclear weapons is dangerous and destabilising. It lessens constraints on their use and makes nuclear war likelier.

The Cold War was fought in the shadow of nuclear Armageddon.

The 1962 Cuban missile crisis came perilously close to initiating an existential war that would have devastated the planet and killed more than 100 million Americans and Russians.

These estimates don’t include deaths from the long-term effects of radiation and the nuclear winter that would follow, blanketing the sun and causing massive crop losses and damage to the Earth’s ecosystem. A 1982 study calculated that if Europe, China and Japan were included, there would be 400 million to 500 million fatalities.

After the close call in Cuba, a new doctrine emerged. Mutual assured destruction recognised that since the US and Soviet Union each had a comparable number of warheads neither could win a nuclear war. Any attempt to strike pre-emptively would be tantamount to suicide since the country attacked would have enough missiles left to annihilate the other.

MAD was satirised brilliantly by Stanley Kubrick in the memorable black comedy starring Peter Sellers as the US President’s eccentrically unhinged scientific adviser, Dr Strangelove.

But MAD worked because it ensured a balance of terror that provided an extended period of strategic stability for the remainder of the Cold War, an era punctuated by the joint acknowledgment of presidents Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev that “nuclear wars cannot be won and thus should not be fought”.

The main concern after the Cold War break-up of the Soviet Union was that “loose nukes” might fall into the hands of terrorists untroubled by moral constraints and undeterred by the superior military power of nation-states. While still a problem, a bigger concern is the emerging second cold war between the US and its authoritarian challengers, Russia and China, which is eroding the trust essential for verifiable arms control agreements.

Most forms of bilateral arms control between the US and Russia have collapsed since the arms control agreements signed by Reagan and Gorbachev in the late 1980s. Beijing has resisted pressure to join new arms control talks, fearful of being locked into the position of a second-rate nuclear power since it has only a fraction of the nuclear weapons possessed by the US and Russia.

Other important drivers of the new nuclear arms race are Beijing’s determination to become a fully fledged nuclear power, Washington’s decision to modernise its nuclear forces and the development of smaller, stealthier and low-yield nuclear weapons.

The outcome of this race is less predictable and even more dangerous than before because there are more players, fewer constraints and greater potential for the proliferation of destabilising nuclear weapons technologies. Today’s nukes can be carried by an expanding list of delivery systems – from suitcases and artillery guns to cruise missiles and super-fast hypersonic missiles.

China’s hypersonic glide vehicle is carried on board a conventional ballistic missile into space before manoeuvring at high speed towards its objective. Russia’s Avangard hypersonic missile flies at 27 times the speed of sound. It carries a two-megaton nuclear weapon with 160 times the destructive power of the nuclear bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima in 1945. The Russian navy even has developed an undersea drone designed to explode and release a cloud of radiation that would make targeted cities uninhabitable.

Technological advances – notably the miniaturisation of nuclear warheads and advances in guidance systems, sensors and satellites – have increased the speed, accuracy and manoeuvrability of the latest missile classes.

They also have reduced warning times dramatically, encouraging hair-trigger “launch on warning” responses that make nuclear war more probable.

In the Strangelovian world, the US president had two hours to recall US bombers from their unauthorised mission to bomb the Soviet Union back to the Stone Age. In the real world, leaders might have only minutes to respond to a nuclear attack.

Former US deputy assistant secretary of defence Brad Roberts identifies three main dangers: sudden developments, such as China’s new missile silos, that unsettle nuclear planning assumptions by one or more armed states; a collapse of the international nuclear order generating a new wave of proliferation and anxieties about terrorist access to nuclear material, technology and weapons; and adversaries who no longer believe the US would use nuclear weapons short of major war.

Another problem confronting the US is its ageing nuclear arsenal. Until 2017, the Pentagon had to use 20th-century floppy disks to control its strategic missiles and bombers.

If unaddressed, the steady deterioration of US strategic forces would increase the likelihood of a missile or warhead malfunction and undermine the credibility of the US nuclear deterrent.

Trump ruffled feathers in Beijing and Moscow by proposing to spend $US1 trillion across the next 30 years upgrading all three elements of America’s nuclear triad (land, air and sea). His 2018 Nuclear Force Posture Review declared new warheads were necessary to maintain the viability of the US nuclear deterrent and to provide more flexibility for a range of plausible contingencies. These new warheads – low-yield variants of the missiles on its nuclear submarines and sea-launched cruise missiles – were heavily criticised as destabilising by Moscow and Beijing, as well as non-government organisations advocating for reductions in nuclear arms.

Despite branding Trump’s warhead initiative as a “bad idea” on the campaign trail and assuring NGOs the current arsenal “is sufficient”, Joe Biden has left intact Trump’s key initiatives and asked congress for a similar level of funding. This has drawn the ire of critics including progressives in his own party, who accuse Biden of expanding nearly all Trump’s programs and have vowed to fight his budget request.

Beijing’s historic nuclear shift must be seen against the background of a fragmenting international order. Confronted with the mega-challenges of the mutating Covid-19 pandemic and a warming planet, the last thing the world needs is a new nuclear arms race and a China determined to close a perceived nuclear gap with the US. But that’s where we are headed.

It’s not just the increase in the number of Chinese missiles that worries our defence planners. Like Russia, China will almost certainly place multiple warheads on each missile to overwhelm defences and allow more targets. Some missiles will be concealed or moved around in a nuclear shell game, making it difficult to know how many warheads China has or where they are at any moment.

A more muscular posture raises questions about whether China might move from deterrence to a more aggressive doctrine that permits a pre-emptive strike against another nuclear-armed state. And it could encourage Beijing to threaten any non-nuclear state that aids Taiwan during a military conflict with the mainland.

Last month a social media video went viral in China after its authors called for “continuously” bombing Japan with nuclear weapons should Tokyo continue to support Taiwan. In the video posted by the Baoji City Council in Shaanxi Province, the narrator says: “If Japan intervenes in military affairs to reunify Taiwan, I must recommend the ‘exceptional theory’ of nuclear strikes on Japan.” This is a clear reference to a theory held by some Chinese officials that Japan should be an exception to the country’s nuclear policy because of Japan’s invasion of China in the 1930s and the infamous Nanjing massacre. It is doubtful the video could have been released without high-level approval because it was created and first released on a Chinese military channel, and was posted after a statement by Japan’s Deputy Prime Minister Taro Aso that any Chinese invasion of Taiwan would be interpreted in Tokyo as a “threat to Japan’s survival”.

The prospect of a nuclear arms race has direct and troubling implications for Australia’s national security interests and requires two immediate responses. First, the Morrison government publicly should support the modernisation of US nuclear forces to maintain the credibility of the US nuclear umbrella. Without it, we would be highly vulnerable to nuclear blackmail by China and North Korea and under pressure to develop our own nuclear weapons. But going down this path would be folly. Apart from stirring domestic controversy, a decision to develop nuclear weapons would be prohibitively expensive, alarm our neighbours and fly in the face of our commitment to the nuclear non-proliferation treaty. A handful of Australian nukes could never replace the protection afforded by the US nuclear guarantee.

Attempts to unilaterally reduce US reliance on nuclear weapons by past presidents have not produced matching behaviour by other nuclear-armed nations. Instead, as Roberts says, “they generated responses by others that increased the nuclear threat”. The Obama administration briefly contemplated a declaration of “no first use” and withdrawing nuclear-capable fighter-bombers from Europe, only to conclude it would heighten, rather than diminish, the risk of conflict.

Almost without exception, US allies fear that any lessening of Washington’s commitment to the longstanding doctrine of extended nuclear deterrence would leave them vulnerable to attack by non-nuclear means. It would certainly constrain Australia from supporting Taiwan in a conflict with China. Without a strong and credible US nuclear deterrent, we would be vulnerable to nuclear and conventional military coercion by China.

Second, Scott Morrison and Defence Minister Peter Dutton need to get serious about missile defence but be clear about what we need and can afford. Missile defence is not a panacea. The US is the only country that has tried to develop a comprehensive system for defending against nuclear attack. The Ground-Based Interceptor System uses land, sea and air-based sensors to detect the launch of ballistic missiles, then launches interceptors to shoot them down. But for all the billions spent, GBIS remains a work in progress.

Other touted solutions such as Israel’s Iron Dome, the Terminal High Altitude Area Defence system deployed in South Korea and the US PAC-3 Patriot don’t meet our needs. Iron Dome is effective only against short-range missiles. THAAD could cost as much as $20bn and is optimised to intercept short, medium and intermediate-range ballistic missiles, not long-range intercontinental ballistic missiles that are the main threat to continental Australia. The Patriot system is designed to counter tactical ballistic missiles, cruise missiles and advanced aircraft. If the Pentagon, with all its resources, can’t reliably shield the country’s major population centres from ballistic missile attack then it would be a futile for us to try.

Our focus should be on better protection for key northern defence facilities and ADF deployments into the region. They are at increasing risk from China’s expanding inventory of potent, highly accurate ballistic, conventional, cruise and hypersonic missiles launched from land, submarines, ships and aircraft.

Working with like-minded countries to establish an efficacious, layered, region-wide missile defence system building on existing capabilities best meets our needs. This means improving and seamlessly integrating the capabilities of the missile interceptors on our air warfare destroyers along with the defence facilities at Pine Gap in the Northern Territory and the space radar and telescope at North West Cape in Western Australia, which provide crucial early warning of ballistic missile launches.

Australians could be forgiven for thinking the end of the Cold War had put to rest the lingering nightmare of a nuclear Armageddon. China’s nuclear breakout should dispel this illusion. Ensuring that it remains a containable threat requires new thinking, close collaboration with allies and a willingness to invest in tailored, affordable missile defence.

Alan Dupont is chief executive of geopolitical risk consultancy the Cognoscenti Group and a non-resident fellow at the Lowy Institute.

There are worrying signs the world is on the brink of a new nuclear arms race. A regional conflict between nuclear-armed states could escalate quickly into a destructive global crisis with catastrophic consequences.