How Toyota Land Cruisers changed the face of modern insurgency

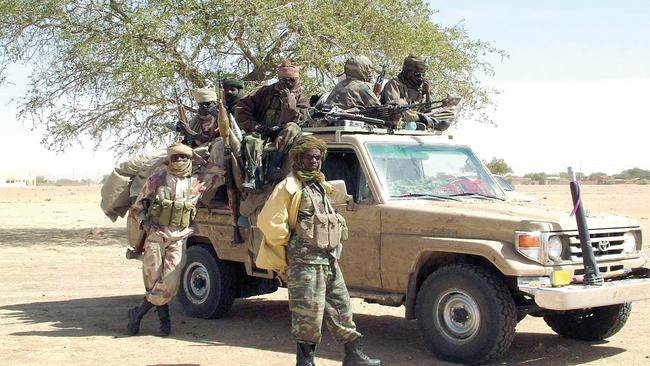

Toyotas changed military mindsets, becoming the vehicle of choice for underfunded, unconventional warfare.

They don’t live long in Chad. Never have. These days, 55 years or so will see them out. Only the people of the Central African Republic – they die right next door – live shorter lives, and only just.

Chad’s is a tortured story of battles with the Sayfawa Muslim dynasty, sultans and Sudan, and a few more recently with itself. Civil wars changed the course of English and American history, but Chad has gone to war with itself four times since 1965 – and lost them all.

For many hundreds of years, a trans-Saharan slave trade route crossed the country, attracting the interest and soldiers of warlords until French colonialists arrived. They might have brought order of sorts, but it was cruel and exploitative. Chad remains one of the poorest nations. It was “granted” independence in August 1960, but by then it had become almost a combat state. Picking up a gun and picking sides was one of the few job opportunities.

About half of Chad’s children attend primary school and about half complete it – 20 per cent don’t live to attend. Malaria and AIDS are big killers. The country has a high infant mortality rate, and almost half its 17 million people know only poverty. The French forced farmers to switch to growing cotton for the French market and to raise taxes from the cash crop to pay for the colonial administration. If a village resisted this, a new chief would be installed. But Chad’s rainfall is inadequate for the thirsty staple fibre. Of course, it is mired in unpayable debt.

Its first post-independence president was Ngarta Tombalbaye who ruled until 1975. He survived half a dozen assassination attempts, including one less often seen these days: as described by Time magazine in 1975, a former ally, Kalthouma Nguembang, the most prominent woman in the country, hired some mystics “to pierce the eyes of a black sheep – symbolising Tombalbaye – and bury it alive”.

It didn’t work and Nguembang was arrested and tortured. By then, Tombalbaye had turned Chad into a one-party state, and, under a policy he called “Chaditude”, asked people to change their French names while he Africanised the names of towns and streets, including its French-named capital Fort-Lamy. This became N’Djamena, an Arabic term for “place of rest”, but some say it can also mean “leave us alone”. Avenue Charles de Gaulle was left unchanged. The French were still paymasters.

Tombalbaye also turned on the Christian churches, reportedly having one pastor sewn into a tom tom drum which was pounded day and night until he starved to death. Others were buried up to their necks and left to die. In an uprising in 1975, the people turned on Tombalbaye and he was overthrown and shot dead, his enemies exercising “their responsibilities before God and the nation”.

After a series of failed transition coalitions, a rebel group led by terrorist faction leader Hissene Habre stormed the capital and took power. It was business as usual from 1982 as – supported by France – he killed 40,000 of his enemies, tortured many times that number, sometimes in the most depraved manner, raped women and favoured his tribe while disadvantaging the others. Rebel groups fought Habre and each other while Libya, watching this shambles, opportunistically occupied Chad’s north. Not many people lived there and Habre seemed not to notice for a while. It was Chad. And it was chaos. But loyally supported by his commander-in-chief, Idriss Deby, Habre hung on.

Then – starting 40 years ago this year – a series of events unfolded that led to the most unusual battle of the 20th century that, briefly, turned Habre and Deby into heroes. It was called the Great Toyota War, and it would save Chad’s bacon while changing the nature of war and insurgency.

In the bartering of territories after World War I, the victors traded lands that were not theirs, including the Aouzou strip, a 100km band of sand between Libya and Chad that had always been the latter’s. Italy controlled Libya then, but before any paperwork was signed to seal this deal Italy fell in with Adolf Hitler’s plans for the world and the strip became contested, but not in an animated way; few cared for the unarmed nomads and their camels living there.

But when ambitious Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi learned that uranium may be beneath those sand dunes, he activated what he claimed was his country’s inheritance.

Gaddafi sent his army to camp on the land while they built an airstrip, claiming it, assuming Chad would not notice and that in any case, the usual mayhem down south would keep them distracted. Gaddafi ordered all government maps incorporate Aouzou into Libya. Early on, he even had the support of some Chadian guerillas. But it turns out only one thing could unite Chad’s government, its warring rebels and random insurgents: the notion that Aouzou was not theirs. Not happy with just the strip he had unzipped from Chad, Gaddafi used it to intrude further into his neighbour.

There were deadly skirmishes, but with France offering air cover, Chad’s ill-equipped defence forces managed to resist and during a two-year lull in the contest from 1984, Habre stitched up deals with his northern rebels. This left Libya’s 8000 soldiers on an archipelago of remote garrisons. Without Chad rebel help, they didn’t know the territory and they barely knew each other; ever concerned about insurrection, Gaddafi kept his army compartmentalised. In the event of an attack, they could not communicate with each other.

By then, wheels were turning within wheels at a high level. US president Ronald Reagan understood before most the terrorist state Gaddafi was constructing and in 1986 ordered a bombing raid on Libya in retaliation for the terror attack on a West German nightclub that killed a US soldier. A recalcitrant France denied the US overfly rights; the bombers detoured more than 2000km via Portugal to Libya. Soon after Reagan sent a delegation to Paris to explain to French president Francois Mitterrand the lay of the land, while offering Habre about $35m in aid.

Unwilling to be further entangled in conflict with Libya, Mitterrand, his troops and planes withdrawn, was advised to help Chad out in another way. France sent 400 Toyota Land Cruisers – with some HiLux models included – to Chad and helped fit them out with tray-mounted antitank missile systems and heavy machine guns.

Africa was about to be reshaped. This would be a little war and it would require a little lateral thinking. On January 2, 1987, Chad sent its flea armada of unbreakable Toyotas across the sands towards the Libyan fort at Fada in the country’s north. Lights off, the lightweight Toyotas sped through the night wide of the town and then further north, while some stayed to its west. (Some of the Toyotas were so packed with soldiers, they looked to be challenging that 1960s stunt of squeezing as many pasty-faced university students as you could into a Mini Minor.)

They attacked together and at first the Libyans thought the cavalry charge from the north – they had placed no landmines there, of course – were reinforcements. When Libya’s laggardly Russian tanks were mobilised, Toyotas would come at them from either side and before the turret could swing around they were destroyed. Chadian soldiers dealt with the rest and by midday 784 of 2000 Libyans lay dead, the rest captured. More than 100 tanks were destroyed. Chad had lost about 50 men.

Gaddafi was a gear man. As long as you could afford the Soviet military hardware – his oil sales meant Libya could – you would win. He sent more tanks and aircraft south, with half-trained, unmotivated reservists summoned for the occasion. Soon his forces were 12,000 strong. His fighter jets bombed sites well within Chad, which enticed Mitterrand back into the fray to knock out Libya’s radar systems.

And then the Toyotas were back. On March 22, Chad’s six-cylinder squadron returned to duty attacking the fort at Ouadi Doum, to Fada’s west, the enemy’s largest base in Chad. In just a few hours, using the same nimble tactics, Deby’s forces killed 1269 Libyans and took 438 prisoners, including the regional commander. Many Libyan soldiers ran away. Chad lost just 29 men. And they added to their haul of imported weaponry reportedly with Soviet-made combat helicopters, a dozen Czech-supplied lightweight bombers and many tanks and armoured vehicles along with rocket launchers and artillery.

Emboldened, Deby led a dazzlingly successful attack on the Maaten al-Sarra air base deep into Libya, killing about 1700 enemy troops and imprisoning another 300. Gaddafi declared victory, then withdrew. By then Chad’s men had reportedly grabbed about $2bn in equipment, killed more than 7000 Libyan soldiers and lost just 1000 themselves.

And the Toyotas had changed military mindsets, becoming the vehicle of choice for underfunded, unconventional warfare, especially in Africa, South America and the Middle East.

Keenest on them have been insurgents including ISIS, the Taliban and anti-government rebels in Somalia, Ethiopia, Nigeria and Syria. Afghan carpet-makers incorporate images of Land Cruisers in their weaves.

The US asked Toyota in 2015 how it was that ISIS had so many. The company replied: “Toyota has a strict policy to not sell vehicles to potential purchasers who may use or modify them for paramilitary or terrorist activities.”

Meanwhile, back in Chad, Deby was purged by Habre and fled seeking sanctuary with Gaddafi while organising resistance forces, before returning to overthrow Habre, who would be found guilty of crimes against humanity and jailed for life in Senegal.

Deby ruled Chad for 31 years during which corruption and cronyism flourished – Forbes listed it as the world’s most corrupt country – while he survived attempts on his life. Eliminating constitutional limits, Deby won six successive elections. While commanding his troops on April 20, 2021, against an uprising by rebels in the north, Deby was shot dead. He’d been re-elected the day before. His son is Chad’s transitional leader. Four months later, Habre died from Covid while still in custody.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout