How Sesame Street went from dinner party to television dominance

Lloyd Morrisett thought that if advertisers could win children’s minds using television, then it could be used to equip them for learning.

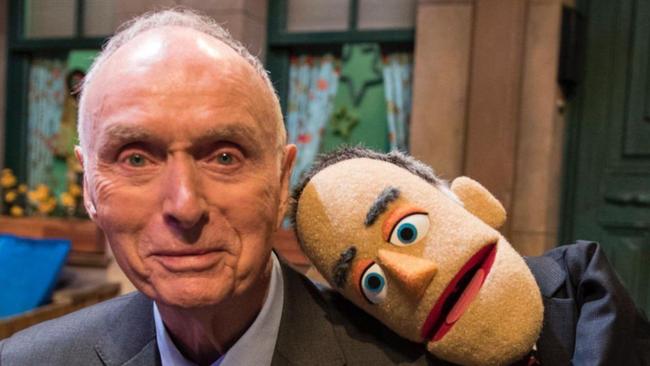

OBITUARY

Lloyd Morrisett, psychologist.

Born: Oklahoma, November 2, 1929. Died, aged 93, January 23.

When Neil Armstrong landed on the Moon in July 1969, mankind – particularly Americans whose technology and taxes did it all – had a right to sit back and think this version of humanity was pretty good. But inequality in America – and in every country – still cast shadows over a nation that had promised in 1962 to put a man on the Moon and achieved it in fewer than eight years.

That milestone was reached with the collective imagination and problem-solving of graduates of one of the world’s best education systems. But not everyone has access to it.

Psychologist Lloyd Morrisett understood that and had wondered how it might ever change. Almost accidentally he brought together three men – none of whom ever met, and two of whom were dead – to fund his education rebellion.

They were Scotsman Andrew Carnegie, the industrialist who became one of wealthiest Americans ever and in 1913 founded the Carnegie Corporation to promote education to the world (it has established 2500 libraries); similarly rich Henry Ford who created the Ford Foundation in 1936 to among other goals “advance human achievement”; and blunt-talking Harold Howe II – a gruff former navy minesweeper captain – charged in the 1960s by president Lyndon Baines Johnson to revolutionise American schools, including violently contested desegregation.

What united these men’s ambitions came about because of Morrisett’s three-year-old daughter Sarah. One Saturday morning in 1965, her dad heard the familiar hum Americans knew as the Indian Head test pattern. It occupied American television screens between the epilogue the previous night and 7am and featured a feathered Indian chief.

It is fondly recalled by the baby boomers who sat waiting for the cartoons Heckle and Jeckle, Mighty Mouse, Tom and Jerry and, Sarah’s favourite, Captain Kangaroo. Morrisett found his daughter staring at the TV, as if mesmerised, singing to herself the advertising jingles that would pepper the children’s shows about to start.

By then, Morrisett had a PhD in experimental psychology – this studies cognition, emotion, memory, learning and motivation, for instance giving birth to sports psychology – and concluded that if his daughter could be taught words and melodies by television then advertisers had plugged into something powerful.

Morrisett found academic life unexcitingly flat, but was keen to work in children’s education, especially devising systems that would bring opportunities for marginalised communities. He returned to New York and eventually rose through the ranks of the Carnegie Corporation.

At dinner with friends in Manhattan in 1966 he asked the host, Joan Ganz Cooney: “Do you think television can be used to teach young children?”

She had been a journalist and publicist for a TV network, but had changed direction to make short documentaries directed at younger audiences. Together they wrote a report – The Potential Uses of Television in Pre-School Education – analysing how TV advertisers had successfully accessed the minds of young viewers and how these techniques could be employed to teach language and numeracy.

Howe, the US Commissioner for Education, invested $5.5m into the plan, and Morrisett brought on board the Carnegie and Ford foundations – the Children’s Television Workshop was born with the goal to “master the addictive qualities of television and do something good with them”.

They began work on what would become Sesame Street – an inventive, fast-moving merger of comedy sketches, live action, animation and Jim Henson’s Muppet characters Big Bird, Oscar the Grouch and Kermit the frog, in a world where fur and skin colour were irrelevant. It was an instant hit when it premiered in 1969.

Within 18 months, it was being watched by millions of children around the world and was first seen in Australia on January 4, 1971.

An early criticism was that children might assume school classes should be as briskly exciting. It has become the most analysed television show in history. Lengthy studies over many years have shown that preschoolers exposed to Sesame arrived better prepared for education, and that those benefiting most were kids from poorer neighbourhoods, particularly boys. These benefits echoed through their lives.

Last month, Sesame Street won an Emmy for Outstanding Preschool Series, the latest of almost 200 won across its more than 4500 episodes. It is the most successful TV show ever.

On its 40th anniversary, president Barack Obama – in an episode brought to you “by the number 40” – appeared to say he fondly recalled watching Sesame Street with his younger sister, and later with his daughters, and enjoyed its timeless values of “compassion, kindness and respect for our differences”.

But Morrisett stood on one set of toes: He was No. 200 on Richard Nixon’s infamous List of Enemies.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout