How can we count the bushfires cost?

Perhaps the biggest economic risk of the fires is that a rattled government launches ineffective policies.

I still remember the hot, ash-laden wind and the ominous glowing embers in the neighbour’s gum trees as my brothers and I were ferried away to our grandmother’s.

We were lucky only the house at the end of the street burnt to a cinder: the wind changed and the fires enveloped nearby Como and Jannali, where they killed four people and wiped out whole streets, along with another 800,000 hectares throughout the state.

Bushfires have long been etched in our national psyche, but our ability to limit their economic and human costs has improved remarkably, notwithstanding the huge damage already wrought in regional Australia.

Criticism of the federal government and now talk of having a royal commission into bushfires obscure what has been a commendable firefighting effort by state emergency services.

In the fire season that began in September, an estimated 10 million hectares may well be burnt across Australia, mainly in NSW, Queensland, and Victoria, and on Kangaroo Island in South Australia, but 25 lives have been lost.

Every death is one too many but contrast this tragedy with the 1994 fires seared in my memory, or the number of hectares burnt and lives lost in 2009 (450,000ha and 173 deaths), 1983 (210,000ha and 73 dead), 1967 (260,000ha, 62 dead), 1939 (five million hectares and 71 deaths).

For all the rancour about “leadership”, Hawaiian holidays, climate change, and intergovernmental political brawls over who’s done what when, this achievement stands underappreciated.

The ability of emergency services to contain the hundreds of blazes at critical points has limited the economic damage to at most half a percentage point off economic growth this year — sizeable but not catastrophic. It could have been a lot worse. “Activity in the most severely affected areas accounts for around 1 per cent of the Australian economy,” noted Westpac economists on Friday.

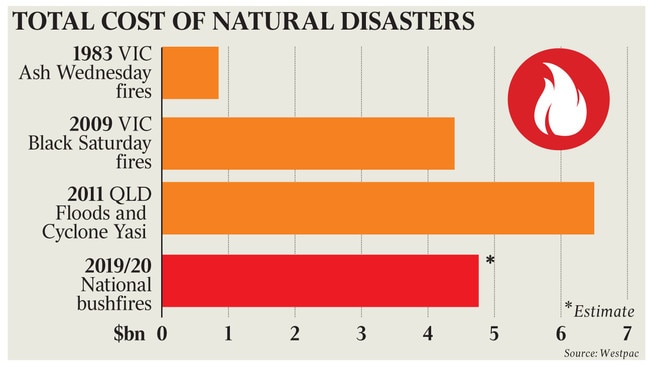

As of Friday, insurers put losses over the period since September at $995m from 11,272 claims, half the damage the April 1999 Sydney hailstorm caused in less than an hour. But it is early days, with Westpac economists estimating that the current fires could hit the economy for $5bn.

A crude measure, although perhaps not much worse than GDP, the ratio of lives lost to hectares burnt has collapsed, all while the nation’s population has been growing rapidly — including an increase in the number of “tree-change” retirees living in bushfire-prone areas.

That said, such enormous, widespread fires will take their toll on an economy already mired in a productivity funk, stagnant in per capita terms for more than a year. Already economists and traders are pencilling in a greater likelihood the Reserve Bank will trim the cash rate to a new record low of 0.5 per cent when its board returns from a summer break next month.

Manufacturing, tourism and agriculture will be the worst-affected sectors. Food prices will rise temporarily, insurance premiums a little more permanently.

Andrew Ticehurst, an analyst at Nomura, expects a boost to the consumer price index of 0.3 percentage points in 2020, due to higher dairy prices. Of course, the aggregate impacts belie outright devastation in some areas.

Respected AMP Capital economist Shane Oliver questions whether the government’s highly anticipated budget surplus will now be achieved this year.

Scott Morrison has promised an extra $2bn in assistance over the next two years. That excludes the hit to the budget from slower economic growth, existing disaster relief programs and the federal government’s obligation to pay 50-75 per cent of the states’ disaster bills once certain thresholds — $250m in Victoria and $300m in NSW — are reached.

Whether the federal budget is in a small surplus or deficit is economically irrelevant. The government might even score political points for sacrificing one of its chief economic goals for the benefit of devastated communities.

If the direct impacts are “quite modest”, as Goldman Sachs chief economist Andrew Boak suggested in analysis earlier this week, in combination with indirect impacts they are massive. Consumer confidence has already slumped — ANZ’s measure crashed to a four-year low this week — casting a pall over the strength of household consumption, already the weak link in economic growth, at least as thick as the smoke that has blanketed Sydney for a month.

A survey by Roy Morgan last year found that about 40 per cent of Australians believed this year would be worse than last. Only 12 per cent thought it would be better, the most pessimistic combination on record.

Economists at UBS reckon a 10 per cent reduction in tourists in affected regions could cost operators $1.3bn. It’s harder to predict the almost certain loss of foreign tourist dollars as images, however exaggerated, of a continent on fire reverberate around the world. Moreover, gross domestic product, still (unfortunately) the favoured measure of economic wellbeing, simply totes up the value of production and income, ignoring the loss of national assets such as millions of hectares of bushland and animals and clear skies.

Even longer-term, more routine fires and smog in cities will weigh on productivity, according to a recent OECD study based on Europe that linked air pollution to a reduction in labour productivity through absenteeism and reduced cognitive and physical ability.

Buried in the ash of the fires is also the prospect of effective federalism in this country. However correct the Prime Minister’s initial response that states are responsible — and well resourced — for fighting fires, it didn’t matter.

The social media rage machine demanded “national leadership” and “action” from the federal government, which will contribute to the further blurring of responsibilities of the two tiers of government in the public’s eyes.

Our bigger states, among the biggest employers in the southern hemisphere, with budgets of up to $90bn a year, can handle fires. They are constitutionally responsible for defence of life and property. If they need help from the federal government they can, and do, ask.

The fires have also damaged incentives. The deluge in private donations, in excess of $140m as of Friday, is a tribute to human generosity and empathy. But if households that haven’t insured are given preferential treatment in the distribution of funds, why bother insuring? It’s hard to resist prioritising the most needy.

Insurers would prefer public and donated funds be spent equally on those insured and uninsured, including on upgrading the quality of public buildings to meet new, tougher standards to withstand future fires, or on fences or general cleaning up, areas not typically insured. Perhaps the volunteer firefighters should receive windfall payments for their sacrifice.

The insured have done their bit. NSW emergency services are paid not from the GST or general state taxation revenue, but overwhelmingly by levies on insurance policyholders, which make premiums about 20 per cent dearer. The uninsured, equally protected by the emergency services, do not pay, encouraging more of them to live in bushfire-prone regions to boot.

Perhaps the biggest economic risk of the fires is that a government rattled by the perception that it has mishandled the fires could launch ineffective policies.

For a start, we do not need yet another politically motivated stimulus to the legal profession via a royal commission. State and federal governments have held numerous inquiries into bushfires for more than a century. Emergency services and communities will learn from the experience without a team of lawyers.

Second, the bushfires have been a political boon for those baying for more “action on climate change”. But we do not need a new set of subsidies for “renewable energy”. That would prove incredibly costly to an economy groaning under high electricity prices. Far better the government seize the agenda, potentially looking at nuclear power stations to seriously cut Australia’s level of emissions.

Discussions about economic costs and incentives can seem miserable when families and communities are still traumatised. Once evacuated, my most vivid memory of 1994 is my grandmother crying by the phone as she learned (as it turned out, mistakenly) that my uncle’s home had been destroyed at Alfords Point.

But it’s no worse than the pious politicisation of bushfires by some to call for more “climate change action”, a call that typically boils down to wanting more subsidies for unreliable solar farms and wind turbines.

This time 26 years ago, my family was evacuated from Bangor in Sydney’s south as fires ravaged the Sutherland Shire.