How Bougainville’s independence vote affects Australia and China

The referendum in Bougainville brings risks and opportunities for Australia and China.

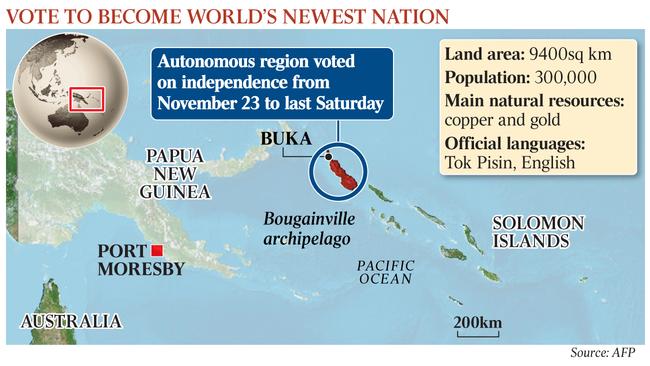

Many Australians are watching the complex unravelling on a distant island following its 2016 referendum on Brexit. Fewer are aware that a referendum has just concluded — with counting now under way — on a very different island, closer to Cairns than Cairns is to Brisbane, which may trigger the creation of a troubled new state on Australia’s doorstep.

The outcome of the referendum in Bougainville could affect Australia’s ties with Papua New Guinea and the region, and create new opportunities for China to expand its influence and boost its controversial Belt & Road scheme on Australia’s doorstep.

About 207,000 of the total Bougainville population of 300,000 registered to vote and a high proportion did so during the 10 days of peaceful voting at 829 polling stations including in Australia and the Solomon Islands. “During polling we witnessed long queues at polling places, we witnessed great enthusiasm,” chief referendum officer Mauricio Claudio says. “So we anticipate a high turnout.”

Independence angst

The vote is a cornerstone of a 2001 peace deal that ended a brutal decade-long war between Bougainville rebels, PNG security forces and foreign mercenaries that killed up to 20,000 people and displaced thousands more. Joyous scenes marked the opening of polling stations two weeks ago, with Bougainvilleans asked to choose between greater autonomy or independence from PNG.

If voters do choose independence, the decision would require ratification by the PNG parliament, whose recently installed Prime Minister James Marape will need to carefully manage expectations within the diverse country.

There is anxiety among some in Port Moresby that Bougainville could set a precedent and spur other independence movements.

But rejection risks rekindling old feuds and skittling the peace process. New Zealand leads an international unarmed police contingent for the vote, backed by fellow witnesses to the 2001 peace agreement: Australia, Fiji, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu.

Bougainville’s land area is just 13 per cent of Tasmania’s, but at 2700m its greatest peak is higher than Australia’s. It is much closer to Solomon Islands capital Honiara than Port Moresby.

The question at the referendum, overseen by a commission chaired by former Irish prime minister Bertie Ahern, was: “Do you agree for Bougainville to have: (1) Greater Autonomy, or (2) Independence?” Most indications point to more than 80 per cent voting for independence.

The outcome will be considered by PNG’s 111 parliamentarians — of whom just four represent Bougainville electorates — and then negotiated between the PNG and Bougainville governments.

If — least likely — the voters opt for continued autonomy, little will change. If for independence, the PNG political establishment will have to decide whether to bite the bullet and concede the potentially ignominious loss of an important part of the nation, or to reject the will of the Bougainvilleans, potentially triggering destabilisation that could see a reversion to the 1990s civil war, for which the impecunious nation is even less prepared today.

Elections for a new autonomous Bougainville government are due next March, providing a potential excuse for PNG to prevaricate on its referendum response. Port Moresby could also back the ABG’s recent, much criticised, proposal to delay that election.

Money matters

Money, or the lack of it, will weigh heavily on many minds during this fraught process.

Last year, the ABG’s budget was $110m. University of NSW professor Satish Chand has calculated that a couple of years earlier, 56 per cent of its revenues derived from local sources — which could reach 76 per cent if Bougainville’s share of the revenues from fisheries were included — the rest coming from PNG national government grants. This financial year, Australia is also providing $36m in development aid.

But Bougainville would be expected to spend far more, if granted independence. This year’s budget for Vanuatu — a nearby nation, also Melanesian, with fewer people — is $537m.

Bridging that gap would be an enormous challenge, unless Bougainville’s ambitions were to be restricted well below Vanuatu’s.

Chand says: “The view large-scale mining will fund an independent Bougainville is shared widely among the Bougainville leadership and local intelligentsia”.

Rio Tinto in 2016 gave away its share of Bougainville Copper, still listed on the ASX, to the PNG and Bougainville governments, which now hold 36.4 per cent each. Rumours constantly swirl that Bougainville Copper or other firms — including from China, Australia, Canada or elsewhere — are on the brink of reopening the huge pit at Panguna, in the mountains above Kieta.

But while Rio, before quitting the chase, calculated the value of the residual copper and gold there at about $50bn, the cost of reopening has also been estimated at $6.5bn or more.

Given the remaining uncertainties, including crucially the attitudes of landowners, and with the mining regime under constant review by the Bougainville parliament, it would seem unlikely that Panguna could reopen any time soon, if at all — although the whole area remains prospective, and in the much longer term might provide an economic underpinning for a sovereign state.

Many lessons have been learned from this history by resource developers in PNG since then, including that a social licence to operate requires providing all the services the landowner communities seek. It’s hopelessly dangerous to rely on the national government to provide them, however great its revenues from resources. This precludes all but the biggest operators from investing in provincial PNG.

Fisheries, rents and cocoa offer Bougainville other income opportunities, but the challenge still seems vast, not least because as development expert Annmaree O’Keeffe, a Lowy Institute fellow, points out, 40 per cent of Bougainvilleans are under 15, further raising government costs.

But Bougainville’s deputy speaker Francesca Semoso told the ABC: “Has there been a country that had everything, and then got its independence? Independence to me is a process. Did PNG have a lot of money when they gained independence? Are we ready? We’re definitely ready.”

And to many Bougainvilleans, the economic barrier appears an irritating artifice. A follower of late independence leader Francis Ona says: “Logic is a white man’s trick.”

China looms

If the money isn’t going to come from the reopened mine, PNG isn’t a likely source. Canberra just lent PNG $170m to help bail out its budget, in deficit by $2bn, with living standards slumping as the birthrate soars and the population edges close to 10 million.

Australia spent more than $1bn stabilising the Solomon Islands through RAMSI over a decade, and recently paid court to its new government. Yet that close wantok (relative/neighbour) of Bougainville switched diplomatic loyalty from Taiwan to China in September, seized a nickel mining project from Axiom, a long-suffering ASX-listed Australian firm, handing it to a Chinese company with a disastrous local environmental record. China’s regional influence continues to grow.

Might China be the answer to Bougainville’s prayer? Momis, a former PNG ambassador in Beijing, is reasonably placed to make that call. But China lends rather than giving grants. And it would only support a Bougainville freed with PNG’s blessing. For myriad domestic reasons, Beijing does not back breakaways.

A freshly minted Bougainville dependent on Chinese support, however, would be considered a wonderful asset, a Belt & Road bastion, by Beijing. An Australia-dependent Bougainville would be more likely perceived as a burden by Canberra. And China just might throw in the investment needed to reopen the mine.

Marape, who became PNG Prime Minister six months ago, astutely appointed the veteran politician and former doctor Puka Temu as Minister for Bougainville, gaining some trust there. But Marape favours autonomy, not independence, stressing the referendum is “non-binding”. “Political independence is meaningless without economic independence.”

If the vote proves as strong for independence as anticipated, he may seek to drag out the process. East Timor took three years to transition from Indonesia. Even PNG had two years of self-government before independence.

The final separation might be postponed until after the next PNG national election, in mid 2022 — maybe leaving history to attribute the humiliating loss to Marape’s successor.

However, a flat PNG rejection of a strong pro-independence vote would risk triggering a far worse train of events, including a vortex of violence dragging in more and more of our region.

Rowan Callick, industry fellow at Griffith University’s Asia Institute and former Asia-Pacific editor of The Australian, worked in PNG for 10 years

Additional reporting: AFP

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout