How a new Olympics voting process was a key to Brisbane’s win

After Annastacia Palaszczuk’s ploy to blindside the federal government, there was a lip-smacking irony in the way Olympics boss John Coates lined her up.

The expectant crowd in the city’s South Bank park and entertainment precinct, wrapped up against the evening chill, mostly missed the big moment on Wednesday. No drumroll to a “Syd-eny”-type reveal. Rather, a crisp, businesslike acknowledgment by IOC president Thomas Bach that the Games of the 35th Olympiad were coming to Australia.

It took a beat for people to cotton on. “Hey,” someone said, “we’ve won.”

But that’s what Bach and the Olympics hierarchy wanted, and it’s a big reason why this country has joined a very select club in securing hosting rights to the summer Olympics for a third time, with barely a generation separating Sydney 2000 from Brisbane 2032.

The International Olympic Committee, custodian of those five gilded rings, has recast itself from the aloof, indulged and self-important crew who behaved like they were delivering manna from heaven to cities paying through the nose to get the Games, to a caring and sharing partner in the deal. Up to a point, that is.

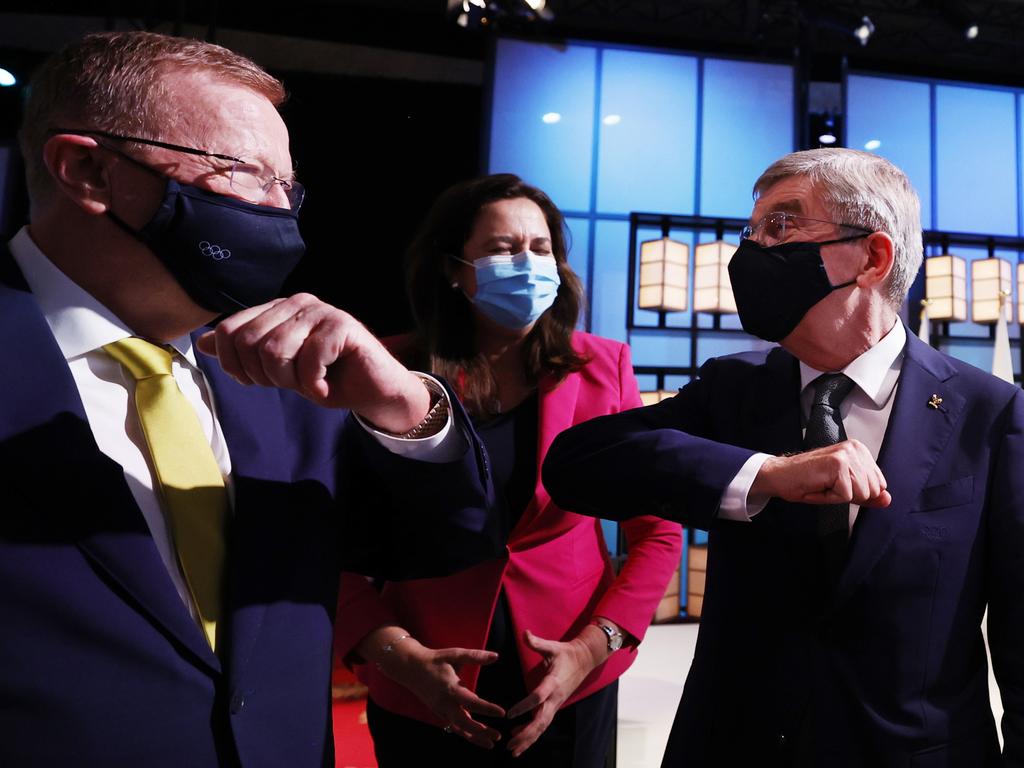

Australia’s Mr Olympics, John Coates, 71, architect of Sydney’s winning bid as well as Brisbane’s two throws of the dice, laid down the law when he insisted that Annastacia Palaszczuk attend Friday’s opening ceremony of the Tokyo Games, whether she liked it or not. A chastened Queensland Premier complied.

The irony was lip-smacking. Palaszczuk had sought to present her flying visit to Japan as all business, not the optional international travel she demonised as a Covid risk in her feud with Scott Morrison over the vaccine rollout. Given her craven ploy to lump a blindsided federal government with half the $1bn cost of redeveloping Brisbane’s Gabba stadium – nearly derailing the 2032 bid, as colleague Jacquelin Magnay revealed this week – there was poetic justice to how Coates lined her up. If she wanted to play in Tokyo, it would be by the IOC’s rules.

As deeply unedifying as this was, it shouldn’t detract from what’s been achieved here. Let’s be clear. Securing the Olympics and Paralympics is unabashedly good news for Brisbane, Queensland, the nation. The Prime Minister was right to call the Games a “ray of hope” in these dark times of pandemic.

Palaszczuk’s opportunism and, hopefully, the virus will have long been in the rearview mirror by the time 2032 rolls around. The new structures set up by the IOC should bury the problematic legacy of past Olympics – the ruinous debt that took Montreal four decades to pay off after 1976; the elephant of a super-sized and rarely filled Stadium Australia in Sydney; the crumbling edifices of Athens’ unwanted venues from 2004 – but that doesn’t mean the Brisbane-based Games are without risk or challenges that will tax the organisers.

Tokyo vividly demonstrates how the best-laid plans can be up-ended by an unforeseen eventuality. Say what you will about Covid-19, but no one saw it coming. The Japanese will spend more than $20bn on a cheerless, 16-day tournament staged to largely empty stands.

The selling point of the Brisbane-based Games is that they really will be different. Coates deserves enormous credit for this. The former lawyer’s clout is reflected in the many hats he wears in world sport: boss of the Australian Olympic Committee since 1990, co-ordinator of every Australian Games bid since Brisbane unsuccessfully vied for the 1992 Olympics, president of the international Court of Arbitration for Sport, member of the IOC liaison and legal affairs commissions for Tokyo, vice-president of the IOC and key ally of the reformist Bach. (The IOC insists Coates recused himself from all decision-making to award the 2032 Games.)

The “New Norm” protocols they have championed to streamline the selection process and drive down the cost of the Games will find expression in Brisbane. The notorious bidding system was dumped in favour of one where a preferred candidate city was identified and then brought along to fine-tune a game plan, making the Queensland capital the unbackable favourite in a one-horse race when the 80 available IOC delegates assembled on Wednesday in Tokyo to vote.

As intended, there was no drama, no late surprises. Brisbane got up by a margin of 72 to five, with three abstentions. It will be the first modern Olympics not to be straitjacketed by the old IOC requirement for every sport to have its own purpose-built venue, a massive saving.

Where possible, existing facilities will be used, underpinning Palaszczuk’s boast that 80 per cent are already in situ, though not necessarily up to scratch. The iconic Gabba will be made over to accommodate up to 50,000 spectators for athletics and the Games’ opening and closing ceremonies; on the other side of Brisbane River, Lang Park, hailed as the nation’s best ground for the rugby football codes, will host Olympic soccer fixtures.

Flexibility is the name of the new-look Games. Athletes will be able to fly in, compete, and fly out rather than stay for the duration; temporary sites, such as those used in the 2018 Gold Coast Commonwealth Games, will be encouraged. Venues for second-tier sports – say, boxing, judo or wresting, which might well share a home – could anchor community hubs including accommodation for the competitors. The athletes’ main village will be central, within 6km of the CBD.

The idea is to deliver lasting benefit to the host city, not a post-Olympics hangover. In Brisbane’s case, the Games will also be outsourced to the Sunshine Coast, Gold Coast and a hinterland extending west to Toowoomba, spreading the expense as well as the experience. “I think this model can work,” says Judith Mair, an expert in events management with the University of Queensland.

Brisbane Lord Mayor Adrian Schrinner is adamant the city would never have gone for the Games under the Darwinian bid process formerly run by the IOC, which effectively cut out mid-size cities unless they were willing to put their solvency on the line. Montreal casts a long shadow.

“This is only possible because the International Olympic Committee changed their method of operation,” he tells Inquirer, having addressed the Olympic powerbrokers in Tokyo alongside Palaszczuk and Coates. “We wouldn’t have put our feet forward if it was the old model.”

Brisbane’s putative operating budget of $5bn is less than a quarter of that for Tokyo. But this excludes many of the fixed costs, such as upgraded transport infrastructure, a hidden trap. Ideally, the Games will be the vehicle to retrofit thickly populated southeast Queensland with the mass transit systems it is crying out for or to fund urban renewal along the lines of the rehabilitation of down-in-the-dumps Homebush for the 2000 Olympics.

Top of the wishlist is fast rail connecting Brisbane to booming beach communities north and south of the city. The $5.4bn Cross River Rail subway into the CBD, due to open in 2025, will unclog the inner network and open the way for an express link to the Sunshine Coast. But make no mistake, the cost will be eye-watering.

The overburdened electric train line to Robina, north of the Gold Coast, is an easier fix, hooking into the light rail system built for the Commonwealth Games, which in turn would be pushed on to connect with the airport at Coolangatta on the NSW border, according to a proposal supported by the RACQ. The Council of Mayors for Southeast Queensland has put up no fewer than 47 major projects for consideration.

The commonwealth will split the cost 50-50 with the state under the funding model accepted by Morrison in April when Palaszczuk put a gun to his head, demanding he sign up virtually sight-unseen to the Gabba redevelopment only days ahead of an IOC deadline. Had the PM baulked – as he was urged to by some in the government, outraged by her antics – the bid could have fallen over then and there.

Morrison, however, has since made it clear there will be no blank cheque for the Games. The federal buy-in, projected to be at least $6bn for infrastructure and associated funding, comes with unprecedented say for Canberra on how and where the money will be spent. Sydney 2000, by contrast, was very much a state project, with the commonwealth contribution limited to $150m, a fraction of the set-up and running costs.

This time, Canberra will be involved in every major decision concerning the Games or projects stacked around them, from start to finish. Morrison says this includes planning, scoping of venues, procurement, contracts and even appointments to the yet-to-be established organising committee and Olympics co-ordination authority. “It’s not just one state running a games and sending us the bill,” he said on Thursday, welcoming Brisbane’s selection.

“No, no. What we offered was to partner 100 per cent and work shoulder to shoulder … and that will be done hand in hand all the way from here to the 2032 Games.”

Schrinner believes the deal could remake the Australian federation. “This will be the first time, I think, in the history of the federation that the Australian government gets a direct say in infrastructure projects,” the mayor says. “Usually, the government just writes out the cheque and the key decisions and the delivery is done by the state or local councils. So this could actually change the federation … and I think that is a very important development.”

Morrison says the Games are projected to generate a return of $18bn in economic and social benefits, which goes to Palaszczuk’s pitch to the IOC that Brisbane will be “cost-neutral”. That would be another departure from Olympic tradition. A 2016 Oxford University study found the Games invariably run over budget. Sydney 2000, costing $US5bn ($6.75bn), had a 90 per cent overrun, according to the research – a relatively modest hit compared to the 720 per cent blowout in Montreal and 266 per cent in Barcelona.

Before we get too carried away with how well we do the Olympics Down Under – reaching back to Melbourne in 1956 – the overrun for the Rio Olympics in 2016 was a relatively modest 51 per cent while Beijing in 2008 came in at just 2 per cent.

Former NSW premier Bob Carr, the man who was famously said to be born without the sports gene, but who got to preside over a successful Sydney Games, says the nation has to accept that the Olympics are going to cost money, and lots of it. But that’s no reason to shun them because the benefits go beyond anything that can be written up on one side or other of a ledger.

“Look, you’ve got to build the infrastructure, do the security, bring in the volunteers – all the stuff that made Sydney successful … and that’s going to cost, there’s no way around that,” Carr says.

“You’ve also got to accept that you won’t get a tourist boom to follow the Games, despite all the claims you will hear to the contrary, and there won’t be a rush of business coming in, either.

“What you will get is a great national celebration, which generates useful international publicity for a middle global power like Australia. It’s a boost for Brisbane and I think modernity becomes Brisbane.”

Call it a giant, fortnight-long party, Carr says, and who doesn’t love a party? Just as long as you don’t wake up with a sore head and empty pockets.

Maybe it was the calculated absence of drama in the bidding process or the grim reality of half a country in Covid lockdown, but you would have to say the announcement of Brisbane to host the 2032 Olympics was, well, low-key.