Hong Kong gives peace a chance

Protesters believe China and police are working to incite violence by planting undercover operatives.

Hong Kongers enjoyed peace on their streets yesterday after the first tear-gas-free weekend in months.

But the remarkably calm march by up to 1.7 million people on Sunday night had less to do with an easing of tension in the city than a new push by protesters and police to win the broad support of the former British colony’s 7.5 million people.

The turnout in the streets on Sunday was extraordinary not just in its scale but also in its restraint.

MORE: March of the brave | Editorial - Hong Kong’s passion for liberty

In torrential rain, Hong Kongers stood side by side for hours in the overwhelmed streets of the Causeway Bay retail district after almost three months of disruption — and amid growing frustrations about the lack of action over what they feel is an existential threat to their city.

And throughout it all, they remained resolutely calm.

Peaceful push

The demonstration was a conscious effort on behalf of Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement to show that it is, at its core, a peaceful cause.

The estimated number of people at the rally varied considerably — organisers put it at 1.7 million, police at less than 200,000. But either way the visual impact of so many people on the streets was impossible to ignore.

Even in the aftermath of the rally, as thousands of people fanned out across Hong Kong island’s main roads, effectively shutting down the city, peace was maintained. The worst of the unrest during the past three months has occurred deep into the night, but on this occasion the protesters urged one another to stay calm and honour the rally’s intentions.

The police turnout for Sunday’s giant rally was conspicuous in its absence.

Officers were almost nowhere to be seen, even when thousands of protesters split off to converge outside the Hong Kong police headquarters.

The only riot police were outside the Chinese government’s liaison office, and protesters stayed away from the area to avoid any chance of conflict.

For supporters of the movement, the lack of violence and the lack of police on Sunday was no coincidence.

Fear of spies

Ms Chen, an advertising executive who declines to give her full name, tells The Australian that protesters believe China and the police are working to incite violence by planting undercover operatives among them.

“Everybody has talked to each other about the need to keep a peaceful mind and not do anything stupid. We know there is undercover police who will try to encourage people to do violent things. That’s why we have to calm down,” she says.

“Some of the people are police from China. They know what people do can trick people’s emotions. I believe that’s what the Chinese government want.”

Among those protesting at the weekend was John, a former Hong Kong police officer. He also didn’t want to give his full name — he still has friends in the force — but he says he felt compelled to stand up to the increasingly aggressive tactics of Hong Kong police in recent weeks.

Police became more hostile after protesters stormed Hong Kong’s Legislative Council building on July 9, he says.

“Because of the 9th, the policy was changed and since then the police have gone mad,” he says.

“That’s my observation as a retired officer. The rules of engagement have changed and they’re more ready to use anything.”

Of particular concern, he says, is the incident that left a young woman blinded in her right eye after she was allegedly shot in the face with a beanbag round by police.

He also condemns the police decision to fire tear gas into a crowded underground train station just more than a week ago. There has been a disturbing lack of accountability among police officers, he says, noting there is no way to easily identifying officers who go too far.

“I think it will encourage police to use force indiscriminately,” he says.

Regaining trust

The massive demonstration on Sunday was designed to counter the reputational damage done to the movement during its occupation of Hong Kong’s international airport last week.

That protest, which forced the cancellation of hundreds of flights in and out of Hong Kong, culminated in violence when protesters seized two mainland Chinese men suspected of being undercover operatives.

The disturbing footage of the men having their hands and feet bound with cable ties and beaten drew widespread condemnation. It provided ammunition for critics of the movement and Chinese state media to paint the protesters as rioters who have lost control.

The movement’s return to its peaceful origins in the hours after those airport scenes was driven organically as the tens of thousands of protesters co-ordinated with one another via encrypted messaging apps and social media.

The movement has shown a startling self-awareness despite, or perhaps because of, a lack of central leadership.

In keeping with its pro-democracy ambitions, many decisions by the movement are made via polls over messaging services.

One such survey, the findings of which were released yesterday, found that about 93 per cent of the more than 90,000 respondents described themselves as “peaceful, rational and non-violent” protesters. The respondents also voted overwhelmingly in favour of more passive means of protest, such as strikes and unauthorised marches, and against more extreme methods such as vandalism and arson.

Perhaps surprisingly for many watching from the West, some 75 per cent of the survey respondents agreed that Hong Kong was a part of China and 74 per cent disapproved of defacing the national emblem.

Despite the latest protest, the movement still seems a long way from realising its five demands: the full withdrawal of a proposed extradition bill with China; the resignation of Hong Kong chief executive Carrie Lam; an inquiry into police brutality, the release of arrested protesters; and greater democratic freedoms.

Facing 2047

There is also the broader underlying reality facing Hong Kong, and particularly its younger citizens, that the city is on an inexorable path towards 2047, when it becomes wholly part of China.

That drives the fear, particularly among younger citizens, that they face a future with fewer rights.

Hong Kong politician Paul Zimmerman says he understands why the movement appeals to younger people.

“I’m 61, so my stake is small, my stake is another 20 years,” he tells The Australian. “For younger people, their stake is another 40, 50 years. They’ve got a much greater stake in this game.”

Zimmerman started out as an expat in Hong Kong but in 2012 gave up his Dutch citizenship to become a Chinese citizen.

“I’ve made a choice with this city and I’m not going to go back on that and cower in Holland and try to get help from the government,” he says.

His immediate worry, he says, is the safety of the young people who are potentially putting themselves in harm’s way.

Longer term, however, there are the more intractable issues facing Hong Kong.

“There is a greater majority of the people of Hong Kong who are concerned about China taking comprehensive control over the city. You feel that, you know that, you do lose a lot of sleep over this,” he says.

“The discussion doesn’t stop. It’s there from the moment you wake up to the moment you go to sleep.”

Young Hong Kongers dominated Sunday’s march, but there were also grandparents, children and even babies in prams.

Benny Wong and his six-year-old daughter Beatrix handed out thousands of flyers they had designed and printed for Sunday’s event.

Styled like a children’s educational poster, the flyer — titled “Hong Kong protest ABC” — featured colourful cartoons alongside the likes of “E is for extradition bill”, “O is for occupy”, “T is for teargas”.

His friend Hei and his five-year-old daughter, Fung Fung, were beside them, handing out their own posters emblazoned with the words, “guard our future”. Wong says he is participating not only for himself but also for his daughter.

“As a parent I will look after my children and I will look after Hong Kong,” he says.

“Hong Kong right now is sick, and I don’t want to to be sick any more. So we are standing up for our children and our future.”

China waits

As Hong Kong returned to normal yesterday, more events were flagged.

Students have revealed plans for weekly strikes once school resumes next month. Another idea that surfaced yesterday involved forming a human chain across Hong Kong and Kowloon.

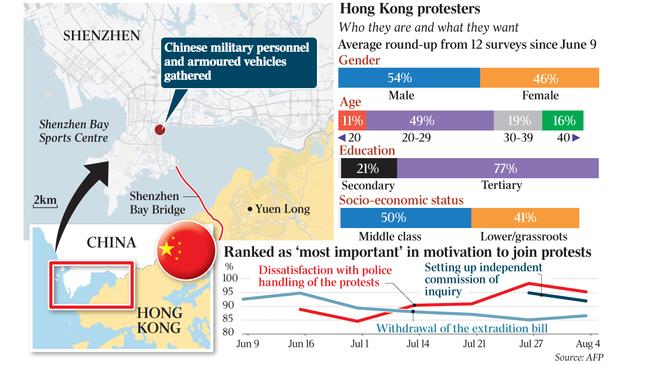

On Sunday, as the protest was winding down, Chinese state-owned television announced plans to boost the role of Shenzhen — the city immediately across the Hong Kong border, where China’s People’s Liberation Army has stationed more military equipment since the movement emerged — as an innovation hub in the greater Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau area.

And Bloomberg reported yesterday that China had moved to block Chinese internet sites from selling protest gear into Hong Kong.

Among the protesters, the sense of distrust — towards police, towards the government, towards China — remains.

But for now, at least, some calm has returned to the streets.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout