Hong Kong: Farewell to China’s most sparkling gem

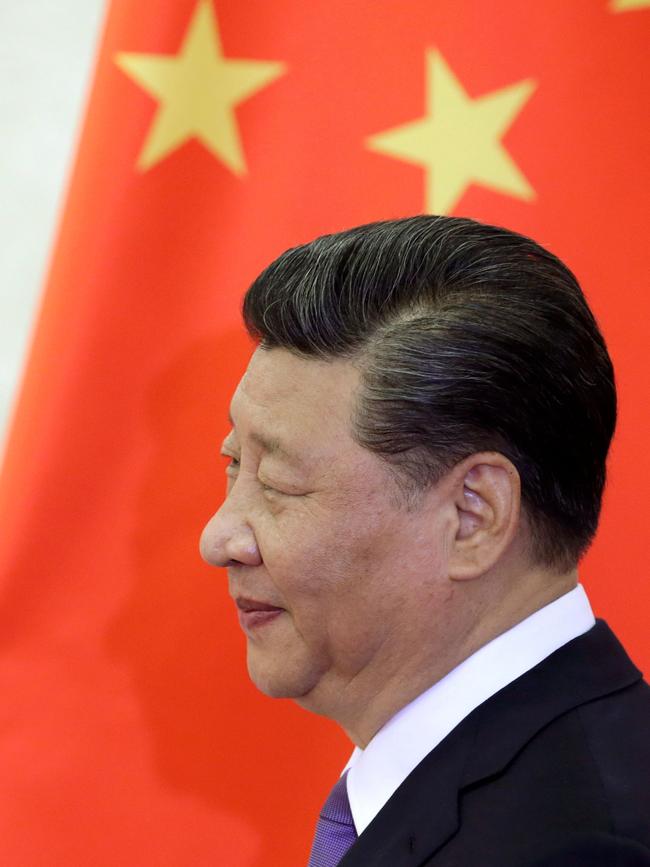

Cosmopolitan, colourful, dynamic Hong Kong is being strangled and swallowed by Xi Jinping ’s bleak dystopia. Where are the noisy elites now?

This is a tale of two cities.

Hong Kong has known the best of times, with its seemingly inextinguishable energy and independence of spirit, and is now becoming acquainted with the worst of times, as it is subsumed into China’s Pearl River delta as merely that region’s fifth-largest city.

Its fate is emerging as an emblematic victory for People’s Republic of China leader Xi Jinping in reversing the global tide that 30 years ago had turned towards liberal democracy with the downfall of the Soviet Union.

Hong Kong, a long-resilient beacon of freedom and the rule of law in Asia, has fallen to the new tide already lapping many shores: that of Leninist authoritarianism, pumped from Beijing.

While the world watched agog and aghast at the tantrums of Donald Trump — whose program will now be repealed rapidly in congress, the sands of time soon enough covering his political career — Xi, a far more historically significant figure, has been marching steadily onward, meeting surprisingly little resistance or criticism among democratic elites.

He said in a speech early in his leadership: “The tide of the world is surging forward; those who submit to it will prosper, and those who resist will perish.”

At the most recent national communist congress three years ago, he stressed that the Communist Party — its “revolutionary ideals soaring beyond the skies” — was engaged in a “great struggle” that requires “drive, ambition, and plenty of guts.”

Xi boasted, with good reason: “The Chinese nation, with an entirely new posture, now stands tall and firm in the East.”

The Economist magazine editorialised recently that in response to this, Western policy towards China — “the 21st century’s ascendant power, an autocracy that mistrusts free markets and abuses human rights” — has become ineffective.

The European Union has just agreed, for instance, an investment deal with Beijing “that secured puny gains and gave China a diplomatic coup”, and the Trump administration secured few meaningful concessions despite “skewering Western complacency about China’s state-led model”.

China is thus succeeding in exploiting Western disarray, The Economist says. The Five Eyes intelligence alliance could enlist only four to agree a statement criticising the latest round of arrests in Hong Kong, with New Zealand’s new Foreign Minister, Nanaia Mahuta, demurring in one of her first major decisions, while Wellington finalised with Beijing an upgrade to their free trade agreement.

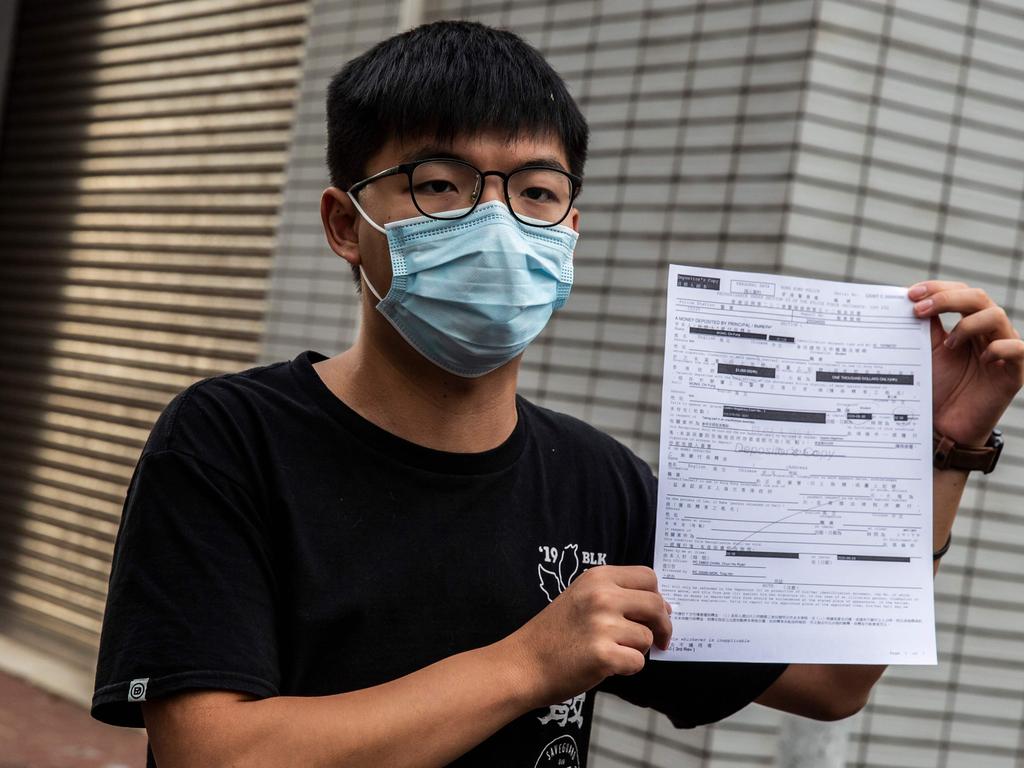

In last week’s arrests, 55 Hong Kong democracy leaders — almost all of those not previously rounded up — were detained under the notorious new National Security Law, for participating in a pre-election primary held last July for the local legislature, which the authorities claimed to be an event “subverting state power”.

The legislature election itself, due last September, was postponed for a year by the China-appointed Hong Kong administration after polling showed that pro-Beijing candidates were set to suffer a drubbing.

The government blamed COVID-19, although other elections went ahead smoothly in Asia post-COVID-19, including in Singapore, South Korea, Myanmar, Mongolia and Sri Lanka.

At the previous elections in Hong Kong, for local government 14 months ago, the pro-democracy movement scored a landslide victory, winning control of 17 of the 18 district councils.

But the great majority of popular election candidates critical of Beijing are now likely to be jailed or otherwise deemed ineligible to stand by this September, virtually ensuring a pro-People’s Republic majority for the next legislature.

As 2021 starts, three of Hong Kong’s best-known public figures, 73-year-old publisher Jimmy Lai and pro-democracy politicians Joshua Wong and Agnes Chow, both aged 24, are behind bars, the former charged and the latter two jailed for alleged crimes of speech and protest — and, in Lai’s case, also for an obscure civil offence relating to the claimed breach of a tenancy arrangement.

Tian Feilong, an associate law professor at Beijing’s Beihang University, told the Global Times that the jailing of Wong and Chow “shows progress in HK’s judicial practice, which had shown a tendency toward over-light sentencing … HK judges are beginning to realise the importance of public order”.

The eloquent Lai, devoutly both Catholic and libertarian, the epitome of Hong Kong entrepreneurialism — he created the huge clothing chain Giordano — and of popular publishing, founding Apple Daily, was at one stage paraded by the authorities in chains. The voice of the Chinese Communist Party, the People’s Daily, branded this Public Enemy No 1 as “notorious and extremely dangerous”.

Enhancing Tian’s pleasure at the HK courts’ tougher sentencing of Beijing’s opponents, Pun Ho-chiu, aged 31, was jailed for 21 months for throwing eggs at a police station. Magistrate Winnie Lau, while conceding “an egg is not a weapon of mass destruction”, claimed throwing them “endangered society”.

The city’s educational structure is being rebuilt from the curriculum up. Libraries and bookshops have been “cleansed” of works critical of Beijing or supportive of liberal democracy. And teachers and university academics perceived as “disloyal” to the People’s Republic of China have been squeezed out or sacked, including a teacher who asked students to reflect on freedom of speech in a worksheet. Hong Kong’s chief executive Carrie Lam said such “bad apples” must be weeded out.

Until China’s all-powerful leader set his sights on seizing firm control of all the levers that count in Hong Kong and steering it into the mainland, it had been a glittering, celestial city, thrilling visitors like no other — even Manhattan, whose energy it once surpassed.

Welcome encounters with Hong Kong and Hong Kongers during visits or through working and living there did much to persuade this generation of Australians that their cultural home is in Asia. But now it is time to say farewell to Hong Kong, to the Hong Kong spirit, and the extraordinary Hong Kong culture.

Simon Pritchard, global research director at Gavekal Research, wrote this week that “the tussle over Hong Kong’s most distinct institution, an independent judiciary”, is contributing towards the “uncertain legal environment”, helping shift the city “away from its role as an open centre for international firms and the globally-focused Chinese diaspora to being a tightly managed city focused on specific functions linked to China’s capital-raising needs and international transactions”.

There is no going back now. Xi operates only in forward gears, and apart from the occasional inconvenient obstacle in his path (Australia is one), fortune has so far favoured his form of Leninist militancy.

I first arrived in Hong Kong long ago, on the last leg of a $20-a-day world tour from my then home in Port Moresby, thinking that I’d already seen everything. How wrong I was. I was enthralled, even before touchdown.

For my plane landed, breathtakingly, between apartment blocks, at the old airport at Kai Tak, where passengers were met by a clamorous mass of welcomers, and I was instantly immersed in the noise and spicy scents of the Eternal City, the Rome of the diverse Chinese Asian diaspora.

The dazzling harbour is bounded by towering office buildings behind which clusters of apartment blocks retreat, wave on wave, to the surrounding hills or to the horizon.

Hong Kong’s status as a free port has been an important ingredient in its economic success, with its 7.5 million population earning an average $A64,000 a year.

The key ingredient of Hong Kong’s success has not, however, been its beautiful mountainous setting on the edge of the South China Sea, its extraordinary infrastructure or its economic freedoms, but its feistily unique people – as I learned while living there in the years straddling the handover and beyond.

It is their energy and independence of spirit that have marked Hong Kong out. That freebooting Australian journalist and Asian identity Richard Hughes 50 years ago described the then British territory as “a rambunctious, freebooting colony, naked and unashamed, devoid of self-pity, regrets or fear”.

It branded itself after the handover as “Asia’s World City” — as the epitome of East meets West, where the best qualities of competing cultures had created a place not only excitingly cosmopolitan, but also uniquely itself. Entrepreneurs based in Hong Kong built businesses throughout east Asia, and the city became a creative hub for the arts, with its ubiquitous Cantopop and its kinetic movies.

However, Hong Kong’s present fate provides a pointer to the future of the nation of which it has for 23 years again been a part: a more uniform China, more rapidly responsive to central direction, with critics managed out of sight.

The old phrase highlighting China’s regional diversity — “the mountains are high and the emperor is far away” — has become redundant as digital governance ensures that Emperor Xi is inside every smartphone, every home and workplace, every pocket and every handbag, and on every street and every train.

Hong Kong is where Chinese firms have previously attracted capital to expand, based on international confidence in the independence of its legal system and of its media holding political and business elites to account.

But this is changing rapidly. Entrepreneurs are not Xi’s favourite company, as illustrated by the slow-motion downing of the famous Alibaba founder, Jack Ma.

Hong Kong’s tycoons, and its key institutions, are also now in play. The last British governor, Chris Patten, said of the conceit that China would never kill the goose that laid such golden eggs, that history was “littered with the carcasses of decapitated geese”.

When Professor Lee Ching-kwan — the director of the Global China Centre at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology — said during an online forum last year that “Hong Kong belongs to the world”, she came under virulent attack from pro-Beijing media and online trolls who claimed that this revealed her lack of patriotism, which is a very dangerous charge today.

Such cosmopolitanism has become in today’s HK a source of suspicion — or, worse, a crime. Its destiny now is not as a “global city” but as a truly loyal PRC outpost.

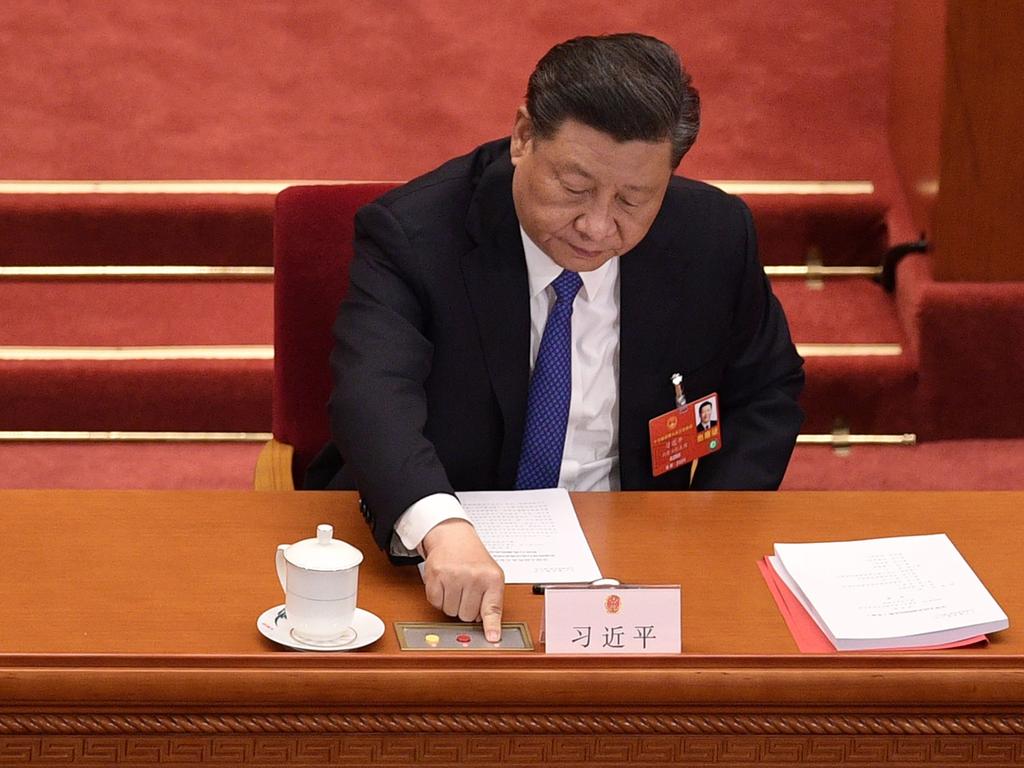

Xi’s masterstroke to subjugate HK, following years of demonstrations for greater democracy by the city’s millennials, was to have China’s National People’s Congress suddenly impose on the city a National Security Law. The congress passed it within 15 minutes of starting its meeting in mid-2020, when COVID-19 had handily constrained HK’s protest movement.

It is more a takeover of key institutions than a mere piece of legislation. Its first article said it was designed to “prevent, suppress and impose punishment for … collusion with a foreign country or with external elements to endanger national security in relation to Hong Kong”.

Almost any contact with a foreigner, or criticism of Hong Kong’s new political and legal regime, or even of the PRC itself, especially if published inter-nationally, thus risks landing the alleged perpetrator before a special NSL court. Under the law, a new National Security Agency deploys agents to analyse, judge and supervise HK’s own administration, and “handle crimes against national security”. This agency is above HK’s jurisdiction.

New crimes include those of speech alone, and cover supporting the separation of HK or any other part of China from the PRC, overthrowing “China’s basic system”, or “inducing hatred towards the PRC or HK governments”.

The sentences range from life imprisonment to a minimum of three years. Trials may be barred to the public, and bail is refused as the default. Cases deemed too “complex”, “difficult” or “serious” for HK will shift to mainland China. Until this month, 40 people had been arrested under the new laws, 39 of them for political speech and meetings, and only one for an act of violence.

This COVID-era closing down of Hong Kong is proving a great China-wide morale-booster for the new Xi-picked party elite, as Chinese media present it as a victory over evil foreign forces and their local lackeys. Buoyed by the comparative ease of subjugating HK, the next expected step is to bring it steadily within the “cyber sovereignty” defensive bulwark, the Great Firewall of China.

The years of protests that began six years ago with the “umbrella movement” had shocked Beijing by showing it was young Hong Kongers who most strongly treasured the city’s core values of freedom and rule of law, while also most zealously pursuing the democracy that they had been denied, by Britain and then by China.

These demonstrations divided the city into yellow (pro-protest) and blue (pro-establishment) camps. By last year, many Hong Kongers had wearied of the protests. But the intensity of the Beijing crackdown in the past six months has dismayed even many of those in the blue camp.

A middle-class Hong Konger tells Inquirer: “People call this law the ‘magic key’ the authorities can use to arrest and jail anyone they like. What the CCP has in mind is total control. They need to do away with the final hurdles like the judiciary, the education system and the social workers who are deemed to be embracing Western values of rights and freedoms.”

As a result, there is an exodus of both people and money, says the Hong Konger. “But the authorities don’t care. They will simply make more new Hong Kongers, people from mainland China who obtain permanent resident status, who will become the ruling elite. The outlook is bleak, and morale is low. Many of my friends are talking about leaving the territory, or at least moving the bulk of their assets overseas.”

Zhang Xiaoming, a deputy director of China’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, said a few weeks ago that “Hong Kong’s administrators must be patriots … and people who are anti-China and cause trouble in Hong Kong must be kicked out.”

Xi has never been at ease with the “one country, two systems” formula bequeathed by Deng Xiaoping. He has succeeded in Tibet, in Xinjiang, and now increasingly in that other once-troubling borderland, Hong Kong, in working to install the party’s version of Han culture as the norm and replacing the ruling elites by cadres who are personally loyal.

Xi’s vision is sincere. Why settle for “world” standards, or “Western” institutions, or even for traditional Chinese culture, which remains more strongly followed in Hong Kong than in virtually the entire Chinese mainland — when a city can instead enjoy the stability and prosperity of the People’s Republic, guaranteed by its unchallengeable and dependable party leadership?

Beijing has defined the essence of Hong Kong’s culture as “capitalist”, implying a distasteful relish for money-making, and viewing the core one country, two systems differential as purely economic. Truly independent courts, legislators accountable to voters, free speech — in general, the concept of a citizenry — are seen as mere accretions that have resulted from British colonial habits, and are thus now disposable.

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian, who posted the notorious photoshopped image of a brutal Australian digger late last year, cited Deng’s vow that after the 1997 handover, “horses will still run, stocks will still sizzle, dancers will still dance”. He added: “We have full confidence that with the National Security Law, these activities will further thrive in HK,” whose unique governance Beijing originally pledged to maintain for 50 years. But gloom is settling among those who uphold values beyond gambling and dancing, with effective Chinese incorporation looming after just 23 years. The former Catholic bishop of Hong Kong, Cardinal Joseph Zen, told Reuters: “We are at the bottom of the pit; there is no freedom of expression any more. We are becoming like any other city in China.”

If populations within PRC regions start to resist, Xi has a simple solution: replace them. Let Hong Kongers who still long for freedom and the rule of law set sail for Britain or Australia, while Beijing opens the HK gates wider for trusted mainland migrants who are eager to make money regardless of values or rights.

Student leader Nathan Law, aged 27, the youngest person elected to the legislature, has found sanctuary in Britain, while pro-democracy legislator Ted Hui recently also escaped — although the HK authorities have frozen his and his family’s bank accounts. Ten young Hong Kongers were recently jailed in Shenzhen for trying to flee by boat to Taiwan.

By contrast, mainland Chinese professionals living in Hong Kong, mostly in the finance sector, have now formed a political party, the Bauhinia Party, named for HK’s floral emblem. With links to the CCP, it may be expected to start winning influence if not also elections. Party co-founder Charles Wong said he was motivated by the HK government’s “weakness”.

Ching Cheong, a veteran journalist in HK, told Radio Free Asia: “The Bauhinia Party is designed to completely replace traditional centrist politics in Hong Kong … it doesn’t work for Beijing to rule directly, so it sets up a political party subordinate to the CCP.”

In November, China’s NPC gave HK’s authorities the power to sack critical legislators without going through the courts. It swiftly ousted four, and the remaining 15 then quit in solidarity, leaving the HK administration to rule absolutely until the election this September, when leading opponents will be in jail or declared ineligible.

Once the pandemic is put back in its box, arriving at Hong Kong’s sleek airport and the sensational train journey into the harbour city will be much the same. The fish steamed with soy, ginger and shallots will taste as perfect, and people will still queue at its brilliant, 100-dish yum cha restaurants. But the city is fast losing its deeper innate flavour, as a model of tolerance and of light for all Asia.

Many around the world grieve with Hong Kong, and will do what they can to help it survive this threat, as it has rebounded from other dark days. Its resilience in the face of the Japanese occupation, and the communist takeover next door, was stirring. But the odds this time are fearsomely long.

The authors of The Hong Kong Advantage, published in the optimistic era of the handover, said: “Hong Kong is a window to the West for mainland China, and a window into mainland China for the West.” But Xi does not like windows. He prefers walls.

In his virtual address last Monday to the Davos forum, he said: “There will be no human civilisation without diversity … Difference in itself is no cause for alarm. What does ring the alarm is … the attempt to force one’s own history, culture and social system upon others … We should stay committed to openness.”

Xi spoke, however, against a massive, eloquent backdrop: a painting of the Great Wall, behind which Hong Kong is now securely installed.

Rowan Callick, author of Comrades & Capitalists: Hong Kong Since the Handover and twice a China correspondent for The Australian, is an industry fellow for Griffith University’s Asia Institute.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout