Homeless for 25 years, Dr Gregory Smith is now enjoying a ‘stunning new chapter’

He lived in the gutters of Sydney and alone in the forests of NSW, a friendless vagrant who seemed beyond help. Now Dr Gregory P. Smith, OAM, has found love, esteem, and a ‘wonderful place called contentment’.

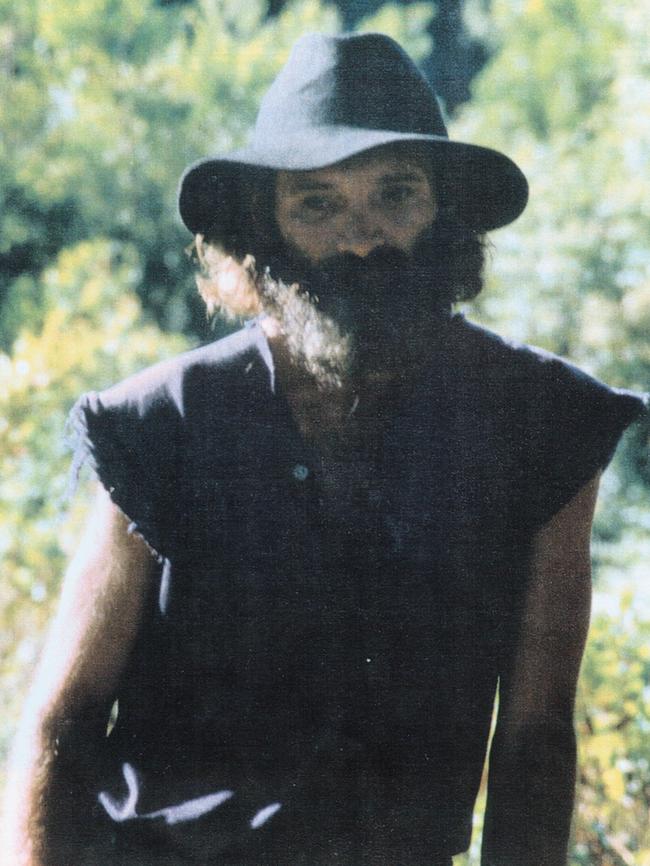

In an earlier life, Catherine Player, a smart young accountant and business manager, might have crossed the road to avoid Gregory Smith, a homeless man with a wild beard and angry eyes. To be fair, most people would have avoided this vagrant sleeping rough on the streets of Sydney and east coast towns, repelled not just by the reek of booze and glaze of drugs. Smith had an air of menace that warned the world: stay away.

Catherine looks across the dining room table to where this very same man is brushing his whiskers over their baby son’s head, eliciting bubbles of laughter, and shakes her head at the thought she would have dropped her eyes and hurried right on past her future soulmate and father to William, born just a year ago.

“This beautiful man,’’ she calls him and there’s pain in her voice at the thought of people turning their backs on him, even though Gregory insists that, for a certain time in his life, that was the only thing to do.

“I was dangerous,’’ he says, the words almost a whisper, as though he’s still growing accustomed to long conversations after so many years of near silence. He was full of anger. A self-described nasty piece of work. “I was best left alone.”

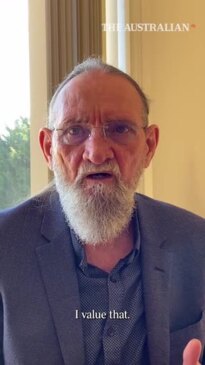

It’s difficult to reconcile this image with the man laughing with his baby in a comfortable light-filled home in Orange in regional NSW. He’s a fit-looking 68 years old with a smart navy jacket, neatly combed beard and ponytail and impressive digital signature: Dr Gregory P Smith OAM, social researcher and senior lecturer, Southern Cross University. He could add author, public speaker, advocate, board member.

He wears his labels with pride because for much of his life he lived under the weight of other tags: sociopath, vagrant, alcoholic, drug addict. A hermit once reduced to living off whatever beetles or worms he could scrounge from the forests in the NSW hinterland, emaciated, mentally broken, and down to his last three teeth.

Does he even recognise that person now? “I try to because it’s important for me not to forget who I was,’’ he says in his quiet, considered way. “I am a very wealthy person with all that experience behind me, I understand a lot more than someone who has always had a comfortable life. I don’t want to forget it or lock it away.

“I want open access to it at any time so that I can empathise, I can talk to people and I can do what needs to be done.’’

Part of that is sharing his story. The extremities of his life have brought wisdom and understanding to the issues of homelessness and child protection, areas ripe with academic papers and good intentions but short on insights gleaned from the depths of lived experience.

When you’ve sunk so low, how do you get back up? When you’ve lived as an outcast, how do you join the world? When you’ve never known love and kindness, how do you build relationships? If you’ve never found peace or experienced joy, how can you be happy?

Gregory P Smith was once the unhappiest man in the world. Now he says he has found something that’s even better than happiness.

The story could barely be believed when it first rippled to the surface seven years ago, of the former forest-dwelling hermit who’d re-entered society, excelled at university and completed a PHD. Media interviews, a book (Out of the Forest), an episode of ABC’s Australian Story and a TED Talk all followed.

Smith’s story wasn’t just one of homeless man made good. It shone light on the Forgotten Australians, the estimated 500,000 people who’d been abandoned last century in orphanages or other out of home care arrangements. Those who’d suffered under alcoholic, violent or mentally ill parents, who’d been dumped in institutional care, all found something they could relate to in Smith’s story.

Growing up in Tamworth, his father was mercilessly brutal when drunk (“violence was so common in our house that for a while I thought every father must beat his wife and children’’) and his mother had her own demons that culminated in a particularly fateful day. She packed young Gregory and his four sisters into the car, drove them to St Patrick’s orphanage in Armidale and left them there without a word of explanation.

Gregory was 10 years old, already imprinted with the scars of a loveless and violent home. The world terrified him. “There were no big people in my life who were kind to me. They were to be feared, hidden from,” he says now.

In the orphanage, separated from his sisters and living under a cruel new regime enforced by the Sisters of Mercy, he grew a hard outer shell to ward off the world. “Before that moment I could at least trust my sisters, now there was no trust anywhere.’’

His mother came back to collect the children 16 months later but the course of young Gregory’s life now appeared set: ward of the state, petty criminal, stints in juvenile detention, scant education, no skills, raging drug and alcohol addictions – and a burning hatred for the world.

Today his childhood trauma would be recognised, professional help sought. But in 1973, at the age of 17 and in remand following a burglary, a psychiatrist casually concluded he was a “personality disordered adolescent, sociopathic type.”

“In hindsight I clearly displayed symptoms of post traumatic stress disorder … back then PTSD wasn’t a diagnosable condition,’’ he says.

In the spirit of self-sabotage that now marked his life, he embraced the sociopath label. People just had to look at him the wrong way and he’d fly at them. “I was volatile, I was angry. I was distrustful. I had been hurt too many times,’’ he says now. “I became established in a way of life that was in conflict with society.”

He found menial jobs, fell in and out of relationships and had a daughter Katie with a woman during a particularly grim period of his life when he was facing arson charges.

He spent most of these years moving around, sleeping rough, bedding down in sand dunes or toilet blocks, until one day, with nowhere to go and nothing else to do, Smith wandered into the forest near Goonengerry in northern NSW and set up a rudimentary camp, his base for the best part of a decade.

Here nobody could move him on or beat him up.

He was 35 years old and could feed his addictions with locally foraged magic mushrooms, a foul home brew and home-grown cannabis he’d sell on the streets of Mullumbimby.

Years later, around 1999 when he left this forest base permanently, he weighed 41.6kg and was talking to aliens and gremlins in full blown episodes of psychosis.

Staff at the Tweed Heads hospital who arranged a Medicare card, disability support pension and tended his medical needs as best they could didn’t expect he’d see out another year.

As Smith sat on a park bench outside the hospital with his worldly possessions – a bottle of rum, a cask of fruity lexia wine, tobacco, marijuana and a gram of cocaine – it was odds-on the nurses’ prediction would come true.

Then he had an epiphany of sorts. He would walk away from his stash, leave the drink and the drugs behind. He would do no more harm to himself or to others.

“These were the first footfalls in an arduous uphill quest for sobriety,’’ he says.

“It was a long hard road.”

Even now, years on from the initial media interviews and his first book, Smith regularly receives messages from people around the world moved by his story or drowning in their own troubles.

Just as the Forgotten Australians drew inspiration from his story, so too did the poorly educated, the people whose schooling was prematurely cut short, because once Smith left that park bench, his road to becoming a fully functioning valuable member of society formally began with a certificate 1 in information technology at a community college then a bridging course at TAFE.

Three years after leaving his forest base he was still homeless, but the wild man was slowly being tamed. He suddenly had purpose in his days, intellectual nourishment. His violent streak had disappeared with the last mouthful of alcohol.

He was meeting people, learning to communicate, accepting kindness from colleagues who wanted to help. “I’d reached a point where I could say a few words to people every now and then. I could even hold a short conversation if absolutely necessary.”

In 2003 he passed the tertiary admissions test and decided to study sociology (“to understand why society and I had long seemed to have a mutual loathing of each other”) at Southern Cross University, funding his studies with a HECS loan like any other student.

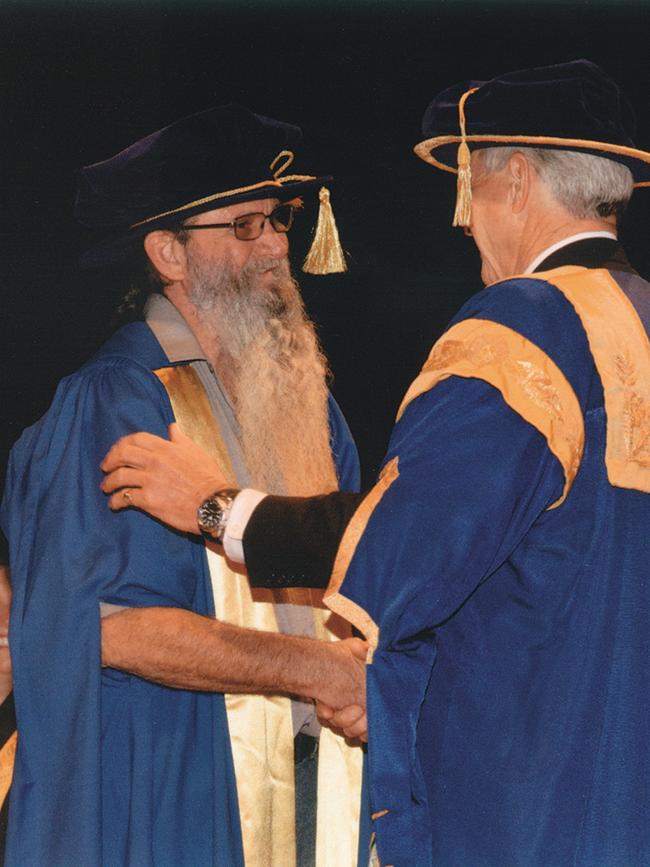

He earned first class honours for his thesis on the experiences of people abused in the same Catholic orphanage where he had suffered as a child. This led to a scholarship to do his PHD, bolstered by employment at the university tutoring students and marking exams.

Now Dr Gregory P Smith is a senior lecturer in the social sciences, a consultant for various homeless initiatives and a board member of the End Street Sleeping Collaboration.

Reverend Stu Cameron, co-chair of the collaboration and Wesley Mission CEO, says Smith makes a vital contribution, not only because of his own experience but because of the deep reflection he has done through academic studies and advocacy work.

“Gregory keeps it real. He brings an innate sense of positivity that something can be done and a unique perspective on what can be done,’’ Cameron says.

As Smith stepped through his recovery, learning to live without the fuel of drugs and alcohol and under the care of a psychologist, his mind turned to reparations.

He’d harmed people, stolen from them. And so he began tracking down people he’d assaulted or robbed, even walking into the Australian Tax Office to confess that he’d dodged tax in various cash-in-hand employment. The NSW police weren’t as forgiving as the taxman when he fronted up to account for his years of unpaid fines: unlike the unpaid tax, the fines had to be paid back.

“Being able to walk free of debt is hugely important,’’ he says now. “There’s a certain freedom in not owing anyone anything, not being obligated to people, not having to look over your shoulder. It’s a release of guilt.”

Gregory P Smith had always muddled through relationships. He’d never bathed in the warmth of genuine care and affection; had no muscle memory for the simple receipt and gift of love.

By 2017, sober and enmeshed in academic life with a growing circle of friends, he’d resolved not to bother with romantic relationships. “I was happy to focus on being a good man, a hard worker, a good friend and grateful to be alive.”

He’d reconnected with his sisters and daughter Katie, and while life wasn’t perfect he finally had a place in the world. And then in 2019, after the publication of his memoir, he was approached to do an interview with a writer called Catherine Player for Regional Lifestyle Magazine. She was 40, 23 years his junior, a busy single mother of two boys, an accountant and business manager in Orange who enjoyed writing on the side.

Their initial half-hour phone interview lasted three hours, the longest Gregory, then 64, had ever spoken to a complete stranger. He was drawn to her intelligence, warmth and humour and she was fascinated with him.

“Nobody else had held my attention for such a long time and I could sit there and listen to him and learn from him, but I enjoyed that we often didn’t agree on things so we challenged each other and that was fascinating,” Catherine says. She found herself calling Gregory for follow-up interviews and soon they were texting or talking every day. “Suddenly months had passed and I thought, surely this can’t still be the interview. We are talking on the phone every day. I thought, what is this? This is more than a friendship.’’

In late 2019 he went to visit her in Orange. Gregory was struck by this “very beautiful, very young-looking woman” who greeted him with a hug. “Since we’d communicated only via phone, our burgeoning relationship had nothing to do with looks, sexual attraction or age. From the very beginning it was grounded purely on human connection and a desire to hear each other’s stories.’’

In March 2020 he relocated to Orange to live with Catherine and her boys Jack, now 15, and Charlton, 11, a terrifying prospect for a man who had no understanding of normal, happy family life.

For someone who’d struggled with the concept of love for the best part of half a century, he never expected to do a crash course on the subject so late in life.

“The first order of business remained the same as when I walked away from the park bench: do no harm.’’ The next steps involved taking it slowly and learning. “To her enduring credit, Catherine was very patient with me.’’

Now with baby William, an active toddler who’s just started walking, he’s a hands-on parent, determined to make only positive memories as they grow together. “I love holding him, feeding him, listening to him and watching him sleep.’’

Has he thought about what he will tell William of his own life, when the boy is old enough to understand? “I don’t know about that,’’ he says with a nervous laugh. “It’s an interesting and confronting question, how do I explore my life with my son without intimidating him or placing expectations on him? All I want is for him to live his own life.’’

He know he needs to extract ultimate enjoyment from every day of this “stunning new chapter of my life’’ because as an older dad he can’t know how long they’ll have together. “I can only do my very best to extend my time through clean living, a good diet, exercise and having a healthy and active mind.”

Is he happy, I ask? The question seems self-evident as he chats with his partner and chuckles with his baby, looking out to his chooks in the back yard and the trees fat with the early buds of spring.

The title of his new book is Better than Happiness and it begs the question: what is beyond happiness? For Dr Gregory P Smith it’s a more permanent and attainable state of being that he never came close to experiencing in the first 50 years of his life.

“It’s a wonderful place called contentment.’’

Better Than Happiness – The True Antidote to Discontent, by Gregory P. Smith (Penguin Life) $35, is out August 22.

The loneliness of the homeless

The first six weeks of a person falling into homelessness is the crucial period for intervention, Gregory Smith says. “That’s when people generally still have connections to their previous lifestyle.’’

After 12 weeks they’ve entered survival mode.

“Once a person enters that mindset, it’s very difficult to get them out and far more complicated,” Smith says.

“They become participating members of a different community – that of rough sleepers.’’

This community has its own set of rules and by 16 weeks the newly rough sleeper has a network, knows where to sleep in reasonable safety, where to get meals.

“Within 16 weeks they’re living a new label they probably never saw coming: homeless. With those labels, however, come excuses, justifications, and rationalisations.”

At this point, Smith says, “helping people is no longer about resources or providing a place where they can be safe, it’s about changing mindsets, overcoming loneliness and confronting despair.”

When people see a homeless person in the street they should just “let them be”.

“Do nothing, there is no expectation for you to do anything. Don’t look away from them, don’t ignore them. They’re people too. Give them a smile and then walk away. At least they know they’ve been recognised and for that moment they’re not invisible. Sometimes it only takes that moment to change a person’s day.”