History is repeated in protests at the death of George Floyd

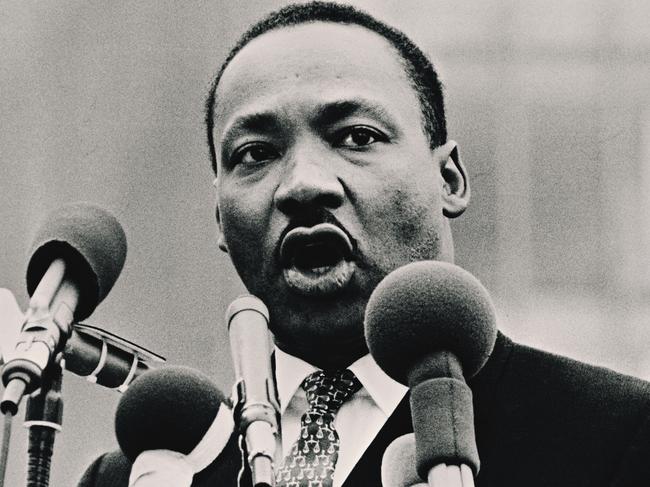

In scope, size and scale of disruption, the US protests over police killings most resemble those in 1968 after the assassination of Martin Luther King.

The President who promised in his inaugural address that “this American carnage stops right here and stops right now” found himself, three years later, being escorted to a bunker in the White House as protests raged outside. At one point, the lights of the presidential residence went dark; intermittent illumination came instead from the fires set on nearby streets.

What began as an expression of outrage when George Floyd, an African-American man suspected of buying cigarettes with a fake $US20 bill, died on May 25, after Derek Chauvin, a Minneapolis policeman, knelt on his neck for nearly nine minutes, has exploded into seething protests nationwide.

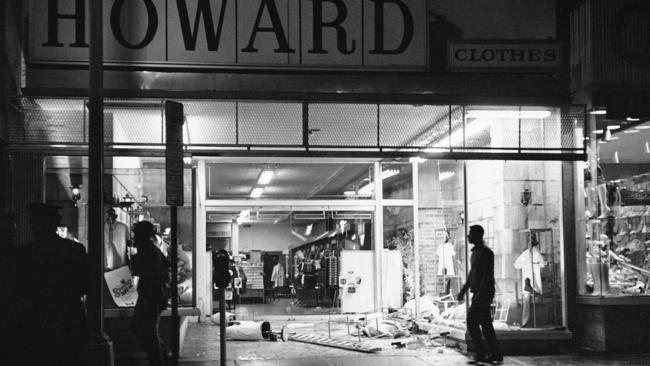

The National Guard has been called in to quell unrest; thousands of people have been arrested; shops from Santa Monica to Manhattan have been looted.

Protests over racial injustice are a recurring feature of modern American life. Their history can render meaning to a protest movement that has spread across America within a week and that has not been pacified by the charging of Chauvin with third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. Why have the protests continued, and been mirrored in cities nationwide?

In scope, size and scale of disruption, the past week’s protests over police killings most resemble those in 1968 after the assassination of Martin Luther King. There were then enormous protests in more than 100 American cities, some of them extremely destructive. Then, too, commentators wondered what the point of the concurrent looting was.

The writer James Baldwin gave this explanation in an interview with Esquire: “Who is looting whom? Grabbing off the TV set? He doesn’t really want the TV set. He’s saying screw you. It’s just judgment, by the way, on the value of the TV set. He doesn’t want it. He wants to let you know he’s there … No one has seriously tried to get where the trouble is. After all you’re accusing a captive population who has been robbed of everything of looting. I think it’s obscene.”

Benjamin Crump, the lawyer for Mr Floyd’s family, echoed that sentiment in his call for protests to continue. “These riots that are erupting in cities all across America are an outward sign of righteous anger,” he said over the weekend.

Are they driven by common sentiments? One month before the severe unrest of 1968, the Kerner Commission, appointed to study the racial uprisings of the summer before, released its report. “White society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it,” it wrote.

Though formal ghettos do not exist today, America remains deeply segregated by both class and race. The convergence of opportunity between black and white America has looked slow and plodding, and in some places, may have stopped altogether. The gap in household wealth — 10 times greater for whites than blacks — is unchanged. The commission’s advice on aggressive patrolling and lack of effective means for complaint seems as relevant today as it did half a century ago.

The 1968 uprisings left deep scars on urban America, hastening white flight and perhaps intensifying segregation. Parts of Washington, DC, which was especially badly affected, did not recover until more than 20 years later. Richard Nixon came to office on the strength of his pledge to restore law and order.

Of course, the events of the past week cannot be reduced to historical repetition. They have more recent precursors, in protests against the deaths in police custody of other unarmed black men suspected of minor crimes — although those have typically been confined to the cities where they took place. The deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014 and Freddie Gray in Baltimore, Maryland, in 2015 sparked huge protests.

They also seeded a nationwide conscious-raising effort, epitomised by the slogan “Black Lives Matter” and the loosely organised movement of the same name. White Americans incensed by racial injustice have been drawn in: unlike previous protests of this type, the past week’s have included sizeable numbers of whites.

Since 2015 The Washington Post has kept a database of all known fatal police shootings. There has been no appreciable drop since the tabulation started — there are almost exactly 1000 such deaths every year.

In cases where the race of the deceased is known, 26 per cent are black, twice African-Americans’ share of the population. Take out cases where the person killed was armed, and the ratio remains the same. Exclude those of people showing signs of mental illness, and the ratio is slightly higher.

The treatment of African-Americans by the police is not a simple issue of party politics. Racial unrest has flared in cities run, like Minneapolis, by Democrats as well as in those run by Republicans. Black Lives Matter took off while Barack Obama was president.

Police departments operate largely autonomously, making concerted reform difficult. Addressing the root causes of disproportionate black incarceration — intergenerational poverty, decades in segregated neighbourhoods with poor schools and aggressive policing — is even harder.

More than 50 years have passed since the Kerner Commission recommended a massive federal project of desegregation and president Lyndon Johnson signed the Fair Housing Act.

Individual police departments have reformed after bruising protests, but nationwide reform requires national leadership. Under Trump that appears unlikely.

If these protests do soon sputter, with their underlying causes still unaddressed, they will, sooner or later, re-emerge.

More Coverage

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout