Hillsong and the business of faith

Scott Morrison’s public faith has put Hillsong Church in a global spotlight.

The Athenaeum Theatre doors swing open and “doof, doof, doof’’ thunders on to Collins Street as the band rehearses for the 4.30pm Hillsong Church service. They call it Sunday church but it feels nothing like it.

The heavy-duty tunes are just the kids having a bit of fun before the next session of Pentecostal rock ’n’ roll, just down the road from the Melbourne Club and a few metres from the city’s town hall. High above the stage the lyrics are flashed on a small screen for the lead singers. It’s Jesus karaoke.

The Prime Minister isn’t here but it’s a fair bet he would love the energy and endorse the sentiments. A few hundred 20-something mainly Asian-Australian worshippers, hands above their heads, shout the Lord’s name.

In the corner sits a blue portable spa, where a few parishioners wearing T-shirts screaming “I have decided’’ are about to undergo a full body dunk. “It’s baptism night,’’ says a woman, clapping happily in the next seat. “It’s wonderful.’’

For Scott Morrison, Pentecostalism is spirituality’s ground zero. It’s a voting nursery and the culmination of decades of work by his soulmate, the church’s globetrotting senior pastor, Brian Houston.

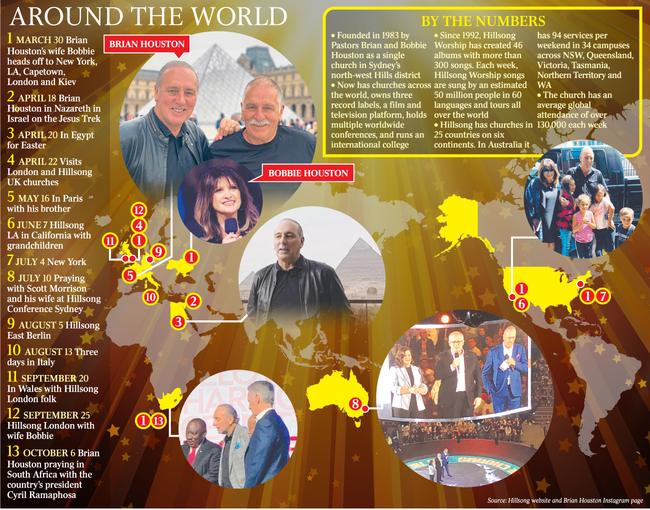

Hillsong boasts attendance of more than 130,000 worshippers a week and its songs are sung by an estimated 50 million people a week across six continents, making it one of Australia’s most visible exports. While Hillsong is not Morrison’s regular church, the Prime Minister is a longstanding friend of Houston, who founded the religious/music franchise sweeping the world with his wife, Bobbie, in 1983.

Until Donald Trump apparently locked the gates to the White House on the pastor, the 65-year-old Hillsong founder was really only a passing mention in the Prime Minister’s broader narrative. But now, as Labor carefully hovers, drone-like, over Morrison’s evangelical Christianity, the spotlight is focused on two things.

First, the extent to which Morrison is prepared to use his religion as a political marketing tool.

Second, the generally quiet way in which Houston has managed to build a religious empire that is spreading across the globe at a biblical rate, selling a Sydney-grown social conservatism built on Pentecostalism. This means anti-gay marriage and a belief in miracles including the resurrection and a wave of optimistic evangelism targeted at the young.

Many of its beliefs are shared by mainstream Christian churches. It’s just how Hillsong goes about its business that attracts the attention. With its sophisticated franchising and its chart-busting, music-driven formula, Hillsong has become so successful globally that its footprint makes it to Jesus what BHP is to mining: big.

It is why an Australian prime minister might have thought its founder worthy of a date with the world’s most powerful man. The Hillsong empire is present across Europe, the US, South America and sub-Saharan Africa.

This is not a multi-billion-dollar enterprise but its reach, via music, enables it to spread its hipster Christianity on the back of connections with high-profile celebrities. Justin Bieber, Kourtney Kardashian, Kylie and Kendall Jenner, Selena Gomez and NBA stars Kevin Durant and Kyrie Irving have all been linked with Hillsong, generating headlines in the US that serve only to attract more young worshippers.

While Deakin University associate professor Andrew Singleton says the growth of Pentecostalism has been dramatic in parts of Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa, the increases have been less extreme in Australia. “It’s gone off like a firecracker,’’ he says of the growth areas, driven by the sort of music that underpins Hillsong.

The definitive story has yet to be told about the White House invitation and the apparent refusal to allow Houston to attend the recent function with Morrison and Trump. But it seems almost a dead certainty that the Prime Minister, or someone second-guessing him, wanted Houston at the function, regardless of Morrison’s obfuscation on the matter.

While Houston has claimed no knowledge of any invitation, he needn’t be too bothered about missing out. His church is rocking.

“Hillsong has benefited from the rise of televangelism in the US and the rise of mega-churches,” David Kirkpatrick, assistant professor of religion at James Madison University in the US, tells The Weekend Australian.

“The type of music that Hillsong was exporting — high-energy, arena rock — was perfectly fitted for mega-churches, which had the technology, the screens upfront, the entrepreneurial spirit to market that to a new generation

“So they kind of stormed through the US as mega-churches were rising up everywhere and they took advantage of this market for their best export, which was their music.”

After setting up a centre in New York in 2010 and Los Angeles in 2014, Hillsong now has operations spanning eight US states including Arizona, Massachusetts, Missouri, Texas, New Jersey and Connecticut.

Every church seems to be built on the same formula: the same money-raising methods, the same internet home page, the same positive messages of lives being changed in the pursuit of Jesus.

In Australia, Hillsong reported cashflows of $103m last year but this is quite possibly understated when considering the eye-watering revenues from its chart-topping music interests. There are multiple Hillsong entities.

Hillsong in Australia, a beneficiary of lucrative tax breaks afforded other churches and welfare agencies, has a habit of erring on the side of disclosure, but like all businesses, is opaque when it wants to be.

In Britain, according to its financial report last year to the UK Charities Commission, Hillsong UK’s revenue was $37.2m for the year. This was a marked increase from the $21.6m recorded in the first available records from 2013.

Of the $37.2m, $30.8m was raised from donations. Hillsong UK members are encouraged at every service to donate up to 10 per cent of their income, as laid out in scripture, to the church. A further $6.2m was raised via its charitable activities.

Tim Costello, former head of World Vision, previously has been critical of Houston’s past preoccupation with wealth as a vehicle to pursue personal achievement.

This was best evidenced by Houston’s 1999 book, You Need More Money, with the internet promotion still declaring today: “Brian challenges you to look beyond yourself, live according to the principles of God and see His blessing on your life as you become a money magnet.’’

Costello, ordained as a Baptist minister in 1987, believes that while the past criticism was valid, Houston has moved on.

“Hillsong is (now) quite different to that,’’ he tells The Weekend Australian. “Hillsong lifts the aspiration. (It says) You can make a difference.’’

When Morrison opened the doors to the media cameras at his own Hillsong-style church in Sydney at Easter, he opened the doors to media scrutiny as well. Morrison does not normally worship at Hillsong but instead attends the Pentecostal Horizon Church in Sydney’s Sutherland Shire.

Yet he is so close to Houston he mentioned him in his maiden speech to parliament in 2008, along with John Howard, senator Bill Heffernan and respected Liberal adviser David Gazard.

Religion has always mattered in Australian politics, perhaps best exemplified by last year’s Catholic education funding wars, when the Coalition was forced to tip in billions to the faith’s schools after bungling the politics of the debate.

Four of the past six prime ministers have been openly religious, with varying levels of commitment, while Tony Abbott and Kevin Rudd were in some aspects defined by their Christianity.

But until Morrison Australia had never had a Pentecostal prime minister and not since former vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin in the US more than a decade ago has there been the potential for a Western political leader to be closely scrutinised for pursuing politics and this brand of faith.

Faith is, of all things, wide open to misunderstanding and bigotry. “I’ve spent a lot of time with Scott and his religion has never been mentioned,’’ one senior Liberal tells The Weekend Australian. “You would never know he was into it. That’s my experience with him.’’

Another Liberal: “Totally overstated.’’

Yet there are, increasingly, public comments made by Morrison that refer to his faith, including his capacity for prayer, although these can often be a reflex action from decades of church going.

Just as a sportsman never loses the desire to catch a passing ball, a parishioner rarely forgets the language of their youth. Indeed, it was reported at the time of the Turnbull leadership challenge that Morrison had been bolstered by MPs supportive of his muscular brand of Christianity.

Morrison did not shy from his faith (and nor should he have to) when commenting this week in Canberra at the national prayer breakfast. “What I like about prayer, and what is so important about us coming together in our parliament and praying, is prayer gives us a reminder of our humility and our vulnerability, and that forms a unity,’’ he said.

“Because there’s certainly one thing we all have in common, whether we sit in the green or red chairs in this place, or anywhere else, and that is our human frailty. It is our human vulnerability.

“It is one of the great misconceptions, I think, of religion that there’s something about piety. It is the complete reverse.

“Faith, religion, is actually first and foremost an expression of our human frailty and vulnerability and an understanding that there are things far bigger than each of us.

“And so when we come together in prayer, we are reminded of that, and we are reminded that the great challenges we face in this world are ones that we need to continue to bring up in prayer. And that is what we do each day as we come together as a parliament.’’

His political language can be peppered with biblical phrases and he was emphatic in July when he told the money-making Hillsong conference: “Our nation needs more prayer.

“My job is the same as yours: love God, love people. We’ve all got the same job.”

And Hillsong is certainly not faith without works. The church does a lot of good, building schools and homes in Africa, providing anti-retroviral drugs to HIV patients, rescuing trafficked sex workers, and providing food and education for thousands in India and The Philippines.

MPs from both sides of the divide who have dealt with Hillsong in their electorates are unanimous in the view that the services are generally positive and the people who go there are well intentioned. “It’s overwhelmingly harmless,’’ a senior Labor MP said.

Yet for all this, Houston has been dogged for decades with the perception that the faith is infatuated with money and keeping up appearances.

Houston sure looks like he lives a rock ’n’ roll lifestyle. The Melbourne Hillsong service was told its senior pastor was on his way back to Australia this weekend after three months overseas. His Instagram account tells the story of a high-flying preacher who spends a lot of glamorous time out of the country.

England, Wales, Italy, Africa, the US, Germany; from one country to the next. France in May with his brother. The Isle of Patmos, Greece, last year for an Easter film shoot. Little seems to be left out of his social media interactions with his followers, which is part of the communications strategy to connect the global empire.

No one seems to be questioning his absences, coming at the same time that NSW police continue to investigate his handling of the fallout of the child sex abuse committed by his father, Frank. Brian Houston was criticised by the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse over the way he handled allegations about his father’s offending.

His travel schedule shows no sign of slowing down. So how the hell does he afford it? His PR agent says the church is now a global operation that requires frequent travel.

But the church won’t say how much Houston is paid.

In 2010, Houston sent a letter to parishioners about the finances of he and his wife.

By religious standards, he was on a huge combined income of $300,000, plus use of a luxury car.

“The truth is Hillsong’s profile means that there are levels of scrutiny on myself and my family, which, quite frankly, does not seem consistent with any other minister of religion or charity CEO in Australia,’’ he lamented in the letter.

“We are very blessed to have the opportunity to speak and preach at churches and conferences all over the world, though our congregation and those of you that know us well know that my first love is building this house, Hillsong Church.’’

The pastor then rattled off his use of a (luxury) Holden Caprice, that his wife drove a three-year-old Audi Q7 ($100,000 in today’s dollars). Personal travel was paid for by the Houstons, he said.

“The innuendos that suggest Bobbie, myself and our children are profiting off people’s tithes (giving) is completely false,’’ he added.

Yet money does talk at Hillsong. Sitting on each Athenaeum chair is an envelope for giving. So tech-savvy is the church that if you don’t have the cash, there is the Hillsong Giving App, an online address to pay with a credit card and BPAY. No giving stone unturned.

For Brian Houston, Google is a blessing and a curse. It wouldn’t have taken much for the White House or the US Secret Service to understand that Houston has a problem. Nor for that matter Morrison or anyone in DFAT. It’s all over the internet.

The child sex abuse royal commission found in 2015 that Houston and his then church’s executive failed a victim who was molested by Houston’s father, Frank, for several years from the age of seven.

Like most things that went before the royal commission, the circumstances are horrid, with Brian Houston, then the national president of the Assemblies of God in Australia, accused of failing to tell the police of his father’s serial sex offending.

NSW police confirmed to The Weekend Australian this week they are still investigating Brian Houston for allegedly failing to report the crimes against the witness, 58-year-old Brett Sengstock.

The commission heard the victim, who today is suffering life-threatening lymphoma, was offered just $10,000 at a meeting with Frank Houston and a Hillsong elder in 2000.

Hillsong and Brian Houston stridently maintain that the Hillsong leader has done nothing wrong, claiming he acted in the best interests of the victim, who was repeatedly abused by Frank Houston in 1970.

Frank Houston, who died in 2004, had extensive child sex abuse form. With the support of NSW Greens MP David Shoebridge, Sengstock is not surrendering his campaign against Houston, Hillsong and others. He accuses Brian Houston of being “very unkind’’.

“I am looked at like a leper,’’ Sengstock tells The Weekend Australian. “They just hammered me. He just wiped me.’’

Pastor Bob Cotton, of the Maitland Christian Church, declares that Sengstock was treated “reprehensibly and disgustingly’’ and has vowed to continue to campaign against Hillsong and Brian Houston. The Weekend Australian sought unsuccessfully to interview Houston, who has always vehemently denied doing the wrong thing by Sengstock.

It may be that the police investigation into the handling of the father’s abuse comes to nothing, as is so often the case with historical sex offending, time erasing most things except the victim’s memory.

But the controversy, as well as being a stain on the Houston family name, is unlikely to disappear even if the Hillsong global leader is cleared by police. The Trump administration and the NSW Greens are unlikely to be the only political outfits to run the ruler over the Houston family’s past.

Labor will be closely watching every development with Hillsong and Brian Houston to determine what, if any, fallout there might be for the Prime Minister, who is now so publicly linked to the evangelist and everything he stands for.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout