Harvesting water: the most lucrative crop of all

Agribusiness planners see the huge potential of northern monsoonal rain.

Many business shopfronts on the main street of the NSW Riverina community are empty and the iconic Federal Hotel remains closed.

The traditional main employer, the SunRice mill, is barely turning over because there’s hardly any rice being grown to mill, and more redundancies are under way.

The population is ageing as young people leave. At the 2016 census, Deniliquin had a median age of 45 compared with a national average of 37, and private studies in recent years have found youth unemployment to be more than 20 per cent.

Rutter, like many in irrigated agriculture communities, points the finger at the Murray-Darling Basin Plan, launched in 2012, under which the federal government has been buying back irrigation licences from farmers to divert water to the environment; she thinks it’s not flexible enough.

“The younger generation don’t feel they have a farm to come back to,” she says.

“The middle generation are encouraging the kids to get town jobs somewhere, and it’s not here.”

For Rutter, who spent many years as a drought financial councillor and is now a local bank manager and president of the Deniliquin Business Chamber, it’s heartbreaking.

“You see a little business kick off in one of the shops, and you say good on you. Then in six months they’ve closed.”

The fate of towns reliant on irrigation agriculture remains highly uncertain, despite the change of weather. While a vast amount of rain has fallen, irrigation farmers won’t necessarily get much of it, at least not any time soon.

“This rain has put a welcome smile on many faces, but we have a long way to go before we can say the drought is over,” Murray-Darling Basin Authority chief executive Phillip Glyde told a Senate estimates hearing on Friday.

“It is even a longer way to go before we see farmers and communities back on their feet.”

Experts say it will take much more rain and likely years before it fills the really big reservoirs in the Murray-Darling Basin, which would make more allocations to irrigation farmers possible and bring the price of irrigation water on the spot market back to realistic levels.

Senior CSIRO hydrologist Francis Chiew says while small storages would fill up quickly when good rains arrived, the big storages would take much longer.

“With multi-year storages, because you have drought for two or three years, it takes almost as long to fill up again,” he tells Inquirer.

This week, the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences Outlook conference in Canberra asked where agriculture has to go next to grow from about $60bn a year now to a $100bn industry by 2030.

A big focus of the conference was the downstream consequences if that task fails in terms of the economies of rural communities.

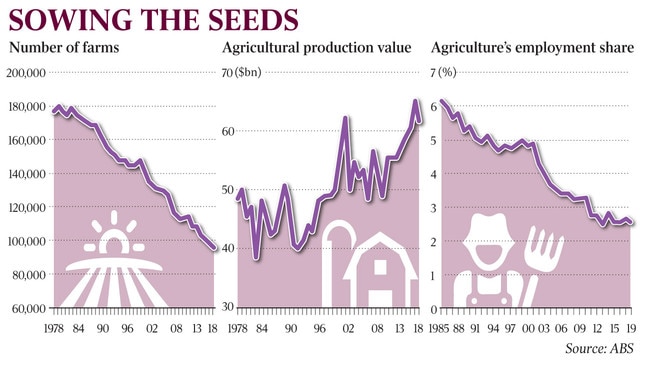

While improvements in farm productivity and economies of scale have kept production rising most years, agriculture’s share of the workforce has declined from just above 6 per cent in the mid-1980s to about 2.5 per cent today.

A key theme to emerge at the ABARES conference was that water — and how and where it is used — is going to be a big part of the equation.

In the Murray-Darling Basin, with climate change, more water yet to be diverted to the environment and many smaller family-owned farms giving way to bigger agribusinesses, smaller towns dependent on old-style irrigation agriculture, such as Deniliquin, will remain in the firing line.

“The larger and medium-sized rural communities are getting bigger, and the smaller ones are getting smaller,” ABARES executive director Steve Hatfield-Dodds told Inquirer when asked about Deniliquin. “If you are specialised, if you only have agricultural employment, you are not in a good space. It’s like the joke about getting to Dublin — I wouldn’t start from here.”

The debate over the basin plan is fierce: those who want it dismantled have launched big protests, lawsuits, and helped get Shooters, Fishers and Farmers candidates elected in NSW state seats. But scientists say the bigger picture in the Murray-Darling is that most of the plan is done, and there is no way more water is going back to farmers.

“We have bought back one-fifth of the consumptive water to turn it back to the environment,” the CSIRO’s Chiew said.

And if the majority view of the climate scientists is right, no matter what governments do or don’t do, it is not going to stop the Murray-Darling getting drier.

“Certainly, if you look at the historical records, and you look at the climate change trend, we are getting more below-average years than above-average years,” Chiew said. “Our winter rainfall over the last 30 years has been quite a lot below what it was previously.”

The drought, the basin plan, and huge plantings of thirsty trees such as almonds have driven up the price of water for irrigation, and that’s not about to change.

“Under the current ABARES medium-term climate scenario, water entitlement prices in the southern Murray-Darling Basin are expected to remain high into 2022-23,” ABARES said in its major outlook report released this week.

ABARES says that, as a result, the structure of what’s grown is likely to change.

Farmers enjoying crops with rising prices or high water-use efficiency, such as almonds, citrus, stone fruit, potatoes, tomatoes and table grapes, would continue to buy water at high prices to grow them.

But growers of asparagus, beans, berries, sweet corn and melons, which had lower water-use efficiency, were expected to raise less of them. “Lower production of fruit and vegetables is expected to lead to higher wholesale prices of fresh produce in 2019-20,” ABARES says.

Some small-scale farmers complain — usually privately — that the water trading system is unfair.

They claim that some of the almond plantations are owned by big, sometimes foreign-owned corporate investors who have deep pockets and are determined to keep them going to produce export crops, no matter if it drives up the price of irrigation water to levels unsustainable for family-run operations. That’s raised debate about whether the state and federal governments should impose limits around what type of crops can be planted.

Free-market economists say no: the whole point of having a tradeable market is for available water to shift to the highest value of production at the time.

Hatfield-Dodds said this had allowed for short- and long-term structural adjustment, which was one reason why agricultural production overall had kept rising.

“We are seeing water shift out of traditional agricultural activity,” he said.

There’s one more key dimension in the water equation.

In the ABARES report is an almost throwaway line: if water availability is going to be progressively constrained in the Murray-Darling Basin, why not take agriculture to where the water is?

“Limited land and water resources in the basin are also expected to increase production trials and investment in regions outside the basin that have reliable access to water, such as regions in Tasmania, the Northern Territory, Queensland and peri-urban areas surrounding major cities.”

Engineer John Bradfield observed a basic fact when he proposed a grandiose scheme in the 1930s to turn the massive rivers of the north down south.

As the CSIRO’s Chiew put it: “Fifty per cent of the water resources we have are in the north.”

Some climate change models suggest that, while the southeast will get drier, the north will get even wetter.

For many in agribusiness, the conclusion is blindingly obvious: rather than endlessly agonise about the Murray-Darling Basin, why not engage in a big new nation-building program to harness the water resources in the north for agriculture and economic growth?

At the ABARES conference, Hugh Killen, chief executive of the Australian Agricultural Company, gave a rousing call to arms along these lines.

“By harvesting water that goes out to the sea, you can open up a new era,” he extolled the audience.

Killen leads the sort of big-scale Top End agribusiness that, he believes, could expand with projects not aimed at Bradfield’s vision of moving water south, which he describes as “overcomplicated”, but using it where it is in the north.

Established in 1824, AACo is Australia’s largest integrated cattle and beef producer, owning and operating a portfolio of properties, feedlots and farms comprising about 6.4 million hectares of land in Queensland and the Northern Territory.

He likes the idea of harvesting and storing the huge seasonal river flows from the monsoons in the Gulf region of Queensland, north of Cloncurry, and storing it in dams. “We would be taking a fraction of the water that flows out to the Gulf of Carpentaria,” he told Inquirer.

Such a project would enable AACo to feed cattle on irrigated pastures during the dry season, reducing the need to transport them to feedlots and “arguably having a lower carbon footprint”.

The federal government has put in some effort towards at least looking into developing big new irrigation schemes in the Top End.

One of the speakers at the ABARES conference was the head of the CSIRO’s northern Australia water resource assessment, Chris Chilcott.

Chilcott outlined possible Top End projects ranging from building $3bn dams to pulling water off rivers and storing them in small on-farm “turkey nests”.

ABARES boss Hatfield-Dodds is doubtful, at least when it comes to major government-funded projects.

“I start with a degree of caution in this place,” he told Inquirer, saying that not many dams pass a cost-benefit analysis.

“Big flashy showcase regional development schemes don’t have a good track record. In most cases, I believe the dams that have been worth building have already been built.”

But to Killen, the choice is simple. He said: “We can continue to put pressure on our existing water resources and assets, or we can get co-operation from governments and industry to unlock the true value of assets in northern Australia.”

Paula Rutter has lived in Deniliquin for a quarter of a century, and she’s watched the agricultural town wither as water trickled away from farmers wanting to grow things.