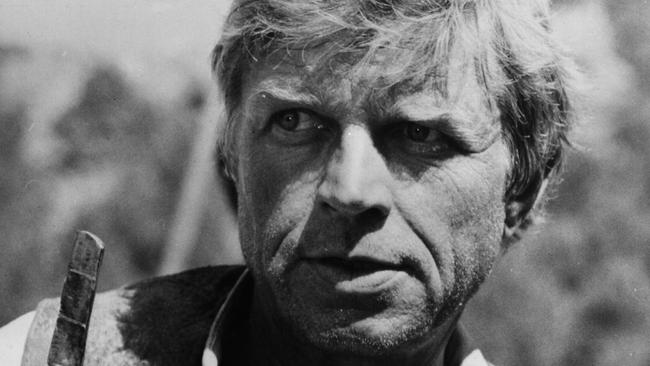

Hardy Kruger was brought up a Nazi, and then played one in his most famous film

Hardy Kruger saw Jesse Owens at the Berlin Games and something unsettled him. Later he understood the full horror of Hitler.

OBITUARY

Eberhard August Kruger

Actor. Born Berlin, April 12, 1928; died Palm Springs, California, January 19, aged 93.

Between the wars, the town of Wedding, outside Berlin, was known as Red Wedding because poor rural Germans flocked there for work, many joining the Rotfrontkampferbund – the communist Union of Red Front Fighters. There were lethal battles between them and the Nazis’ Sturmabteilung – Storm Division.

Locals had to choose sides. Hardy Kruger’s parents chose the Nazis, and Kruger’s loving parents raised him to be one. His mother believed Hitler could save the world and had a bust of him on the family piano. The school to which they sent him had a portrait of Adolf Hitler on the wall. His high school was one of the elite Adolf Hitler Schools, at Sonthofen in Oberallgau, a castle built in 1934 in the south of the country that Hitler saw as educating “an endless stream of German blood and of German life” to be consigned across his conquered lands.

When World War II began with Germany’s invasion of Poland in September 1939, Kruger was 11 but fully onside with the Fuhrer, if too young to be part of the Hitler Youth. (On the other side of the country Joseph Ratzinger, later to be Pope Benedict XVI, had been born a year earlier to a family harassed for agitating against the Nazis. Nonetheless, he was enlisted by the Nazis aged 14.)

While at Sonthofen, the handsome student was used as an actor in a propaganda film, Young Eagles, and about that time met actor Hans Sohnker. The already famous Sohnker would disparage Hitler to the students: “Your Fuhrer is a criminal.” For the first time Kruger began to question his country. But something had struck him as odd years before, as the boy attended the 1936 Olympic Games with his father. It is debated to this day if Hitler saluted Jessie Owens or not, but Owens’s four gold medals unsettled the notion of Aryan superiority.

Early in 1945, and not yet 17, Kruger was seconded to a new combat division of the SS which, though barely trained, engaged the Americans in heavy fighting.

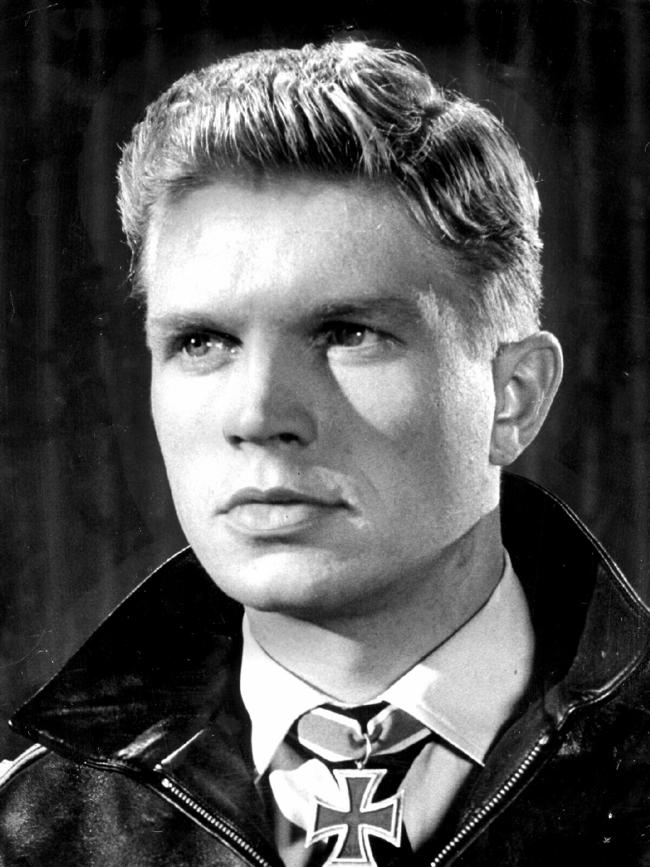

Six years ago he told a reporter: “I had to behave at the front as if I were shooting at the Americans, even though I always missed. Black faces rolled past the barrel of my submachine gun, and it made me think of Jesse Owens.” He was sentenced to death for cowardice, but this was vetoed by a more senior officer. He deserted, first to Hamburg, later Hanover, where, after the war, he started working in low-level German films. His break came when producer Roy Baker overruled Rank Studio’s choice of Dirk Bogarde to star in the 1957 film The One That Got Away, the remarkable story of Franz von Werra, the only German soldier to escape in World War II.

Probably shot down by an Australian, Flight Lieutenant Paterson Hughes, over Kent on September 5, 1940, Werra made endless brave bids for freedom, was shipped to Canada and jumped from a train window in midwinter to cross the frozen St Lawrence River to the US, then on to South America and finally Germany via Barcelona. Hughes was killed two days after their encounter, after hitting the flying wreckage of a bomber he had downed.

The film made Kruger a star. His next big movie was Hatari! with John Wayne (it was to have been Clark Gable, but he died suddenly) filmed at a farm Kruger had bought in Tanzania while travelling on his improved earnings.

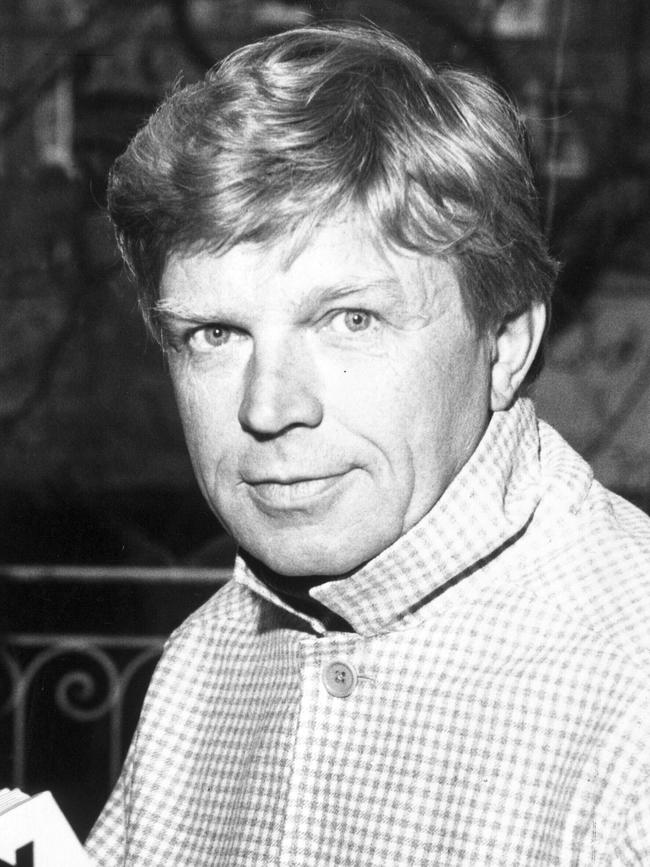

He would go on to more action movies including The Flight of the Phoenix, A Bridge Too Far and The Wild Geese, while always working in Europe where he starred in the almost-overlooked, but Academy Award-winning Sundays and Cybele, which might never have been made but for Kruger’s enthusiasm for it.

He starred in Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon, another underappreciated film that still won four Oscars, and these days is considered a landmark movie.

Kruger retired from films in 1984 to concentrate on writing an autobiography, some novels and travel documentaries that he also directed for television.

Late in his life he reflected on his parents’ enthusiasm for Hitler. He had spoken to his mother about it: “After the war she understood what went wrong and that I was given the wrong upbringing. She felt guilty.”

Kruger was unable to have that conversation with his father. At the end of the war when Berlin was divided between the Allies and the Soviets, Wedding was cut in half. Kruger’s father was arrested as a member of the Nazi party and whisked away by Soviet troops to a camp where he died.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout