Google is keeping an eye on you

Google is watching as you shop, walk and sleep. How much info can we really afford to give away?

A couple learns they’re having a baby. They are exhilarated but careful about who they initially share this information with. Unfortunately the tracking capabilities of their phones are not so discreet.

The tech giants can work out a pending baby in many ways. Location tracking can reveal regular visits to an antenatal clinic, or changes to your purchasing habits, such as buying calcium and magnesium supplements or various medicines.

Sometimes the news leaks out inadvertently. There was the recent case of Gillian Brockwell, a writer for The Washington Post who wrote a public letter to the tech giants in December. It implored them to stop bombarding her with maternity-related ads after her baby was stillborn. She admits she probably looked up maternity wear on Google, clicked baby-related Facebook ads, or maybe used #babybump once too often as an Instagram hashtag.

The ad tracking was not clever enough to work out hers was one of the 24,000 stillbirths in the US every year.

Privacy given away

In the digital age we seem to accept we have less privacy. But there are circumstances where we will regret that. It takes an experience such as Brockwell’s to realise how detrimental the loss of privacy can be. Generally we accept a trade-off: Google and Facebook give us access to their platforms and tools for free, and we give them some information in exchange.

But how much information can we afford to give away? Could we be losing all control over our privacy?

In 2019, we’re barely holding on to our privacy, thanks to the bevy of sensors that turn phones into perfect trackers. Our phones spend more time telling Google what we’re doing and where we go than we spend on calls and texting.

Google is in the box seat because of its dominance in the Android world. About 90 per cent of the world’s two billion phones are Android handsets that use Google’s Android operating system.

Google can scavenge information about people, glean their location, interests, product choices and habits from the huge volumes of data it collects from browsers, smartphones and other devices.

Sham assurances

This data-collection capability is out of control. Google says it asks users to approve sending phone data to its servers. It says much information is anonymous, and users can tweak privacy settings to limit tracking.

However, if you believe US multinational Oracle Corporation, Google’s assurances are a sham. Oracle says Google’s privacy policy is effectively a recipe for data collection that allows it not only to collect supposedly anonymous data, but to cross-reference it with its own data and to link specific users with it.

It says Google tracks you when your phone is asleep and keeps records of your location and purchases even if you don’t have a Google account or you are not logged in. It says even if you are not connected to the internet, Android phones can store two days of data and send it to Google once you go online.

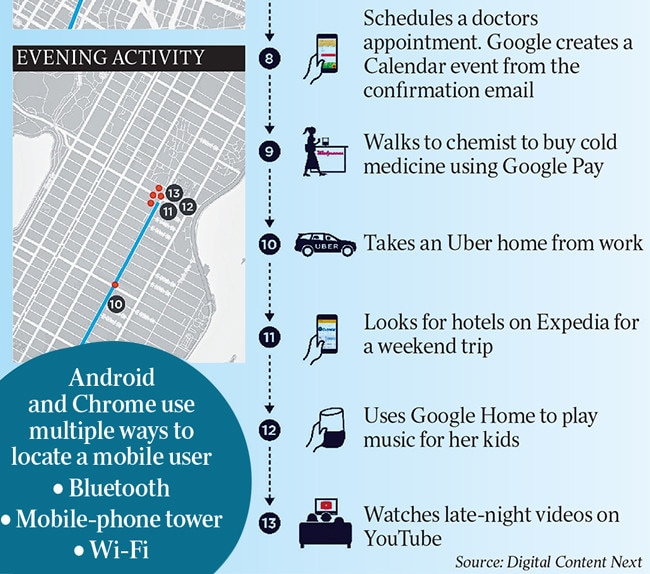

Going indoors is no escape. The combination of a barometer in a phone and nearby Wi-Fi modems and Bluetooth beacons can establish which shop you are in.

Taking on Google

Oracle has been selling this message in Australia too. In May last year, there were headlines around Oracle’s claim that Google harvested a gigabyte of data every month from Australian mobiles, which, among other things, meant users incurred increased data usage costs. Users collectively were paying $580 million extra in data charges. Oracle accused Google of paying Australian telcos to pass on the data.

The Australian Competition & Consumer Commission stepped in to investigate, although it hasn’t finalised a response. “We are not in a position to provide any further update,” a spokesperson says.

Oracle has a motive for taking on Google. It is involved in a $US8.8 billion ($12.4bn) lawsuit claiming Google built its Android operating system without obtaining the licenses needed to use the Java programming language. Oracle gained ownership of Java after acquiring Sun Microsystems in 2010. The litigation has been under way since 2012, with Google this year challenging court rulings in Oracle’s favour.

Oracle is not alone in its concern. In its preliminary report on digital platforms, the ACCC says Google gives users the option of turning off location history, “but turning this setting off does not prevent Google from continuing to track users’ location via the web & app activity setting”. Its final report is due by June 30.

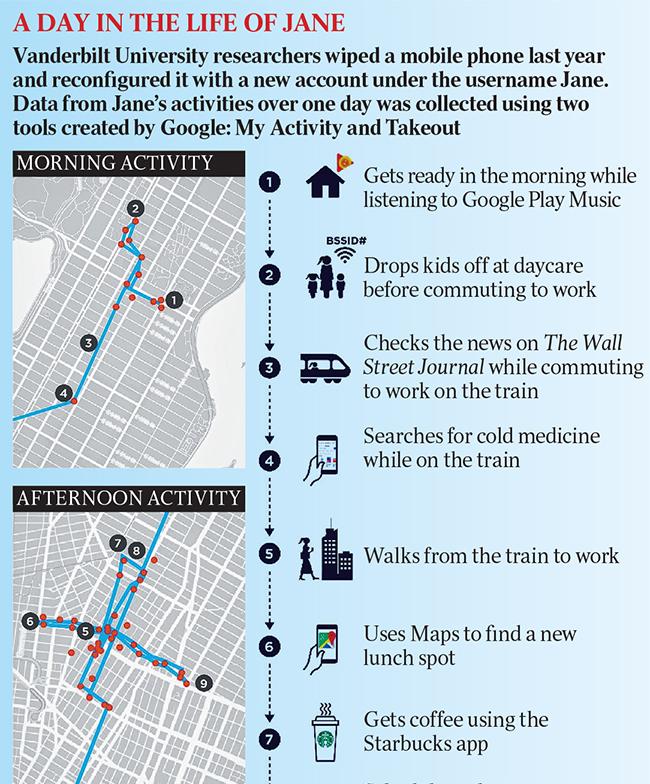

Oracle cites a study published last year by Vanderbilt University in Tennessee, authored by Douglas C. Schmidt, an expert witness in the trial. The study involved setting up new Android phones and monitoring the information they passed to Google. It looked at data mined from an idle Android phone and found the device sent data to Google’s servers an average of 14 times an hour, 24 hours a day, without a user initiating anything. Information included location data gathered from wireless networks, hot spots, cell towers and Bluetooth beacons while a user walked around.

■ How to protect your privacy on smartphones

In one Schmidt test, during a 15-minute walk Google collected 100 unique identifiers about a user’s actions from public and private Wi-Fi points. The study also found Android phones communicated with Google nearly 10 times as frequently as iPhones communicated with Apple.

Google’s response is that users can opt out of data collection. It rejected the study, saying it was no surprise the report contained “wildly misleading information”, given Schmidt’s role in the court case. Schmidt’s response was to say Google had not identified any specific aspects of the report’s methods or conclusions as “erroneous”.

Oracle says Google gets around users trying to remain anonymous by using different identifiers in the data transmissions. Data sent to Google might be labelled with a user’s ID or username, an “advertising ID”, the Android certificate ID, the device’s IP address, a phone’s unique ID, known as the International Mobile Equipment Identity, or a serial number on the phone’s hardware. If there’s no username, you can be identified by a phone’s IMEI.

Oracle claims Google can cross-reference these identifiers to put together otherwise disconnected data about users.

This is a particularly sinister finding, because it implies that anonymous data can still identify specific users.

Then there’s tracking carried out on third-party websites. Google’s cookies collect information on websites you visit. This can be cross-referenced with your Google ID if you are using Google on another web page.

Combining data

In its submission to an ACCC inquiry into digital platforms, Oracle says users unwittingly authorise Google to perform this cross-referencing, which is contained in its privacy policy, known as a “data collection policy”. The policy lets Google combine data it collects from different sources to better understand user activity.

There’s further concern that Google doesn’t reveal the full extent of information it collects. Oracle says Google has a service called Google Takeout that lets users create an archive of the data Google collects. But in fact the archive contains only part of the data Google sweeps up.

“As evidenced by network transmission logs from Android devices, there are specific gaps between what a Google Android user’s device collects and the information Google reveals in a consumer’s Takeout data.”

Missing data includes information on nearby Wi-Fi base stations and Bluetooth beacons used to establish location.

Oracle says the data contains granularity to a level that would help Google work out precisely which shop you are in. It is also less taxing on the battery to calculate location in this way rather than using GPS.

Oracle also claims Google has created a massive database of Wi-Fi access points and Bluetooth beacons to aid this accurate location tracking.

“With more than two billion active global Android users, Google can maintain a detailed database of access points updated constantly by the movements of unwitting consumers,” the company says in its ACCC submission.

In his report, Schmidt details a day in the life of a Google user. The report says Google collected user data such as location, routes taken, items purchased, credit card activity and the music to which the user listened. More than two-thirds of the information was obtained through passive means.

The report says the frequency of these communications increases significantly when a user starts moving around or uses the phone, without necessarily accessing any Google apps or services. “Such data constituted 46 per cent of all requests to Google servers from the Android phone.”

Location data was collected at 1.4 times the rate when a user was moving around as opposed to stationary.

Oracle says data can be collected through Google Analytics even if a consumer doesn’t have a Google account.

It says Google tends to be more open about these practices in the material it sends to advertisers. Google tells advertisers that when users aren’t signed into a Google account, it can estimate their demographic information using a cookie.

Incognito mode

Then there’s “incognito mode” in Chrome. Google says Chrome won’t save your browsing history, cookies and site data. However Oracle says Google still tracks the consumer. It cites a letter to the US House of Representatives judiciary committee from Google chief executive Sundar Pichai.

“When a user conducts a search on Google in Chrome Incognito and signed-out modes, we set a cookie to correlate searches conducted in the same Incognito window during the same browsing session.

“We will, however, use certain factors … such as the browser type, language, time of search, location (or an estimation of location), and prior browser session searches, to improve search ranking relevance for the user’s query.”

Google declines to comment on the Oracle submission. However, its submission to the ACCC inquiry says it gives users an ability to delete and manage their personal information from Google services. That includes deleting their search history.

It says that in 2011 it was the first to let users delete their data with the “download your data” (Takeout) tool.

The company’s privacy policy and My Account website explains what information Google collects, why they collect it, and how users can update, manage, export and delete information.

It uses location history to deliver better results and recommendations on Google products, but users can opt in, edit, delete or turn it off at any time.

Smartphone data harvesting is one of many issues social media platforms face amid growing concern about their operations. Others include user privacy and data security, following the Cambridge Analytica debacle, the use of social media by terrorists and the control of live streaming following the Christchurch massacre, de-encryption and how far to co-operate with security services, ad pricing, cyber-bullying, hate speech, news ranking and fake news.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout