Yasha was 95 years old. I wrote about him in a piece I published on my substack – Gawenda Unleashed – a couple of weeks ago: The Jewish warrior, I called him.

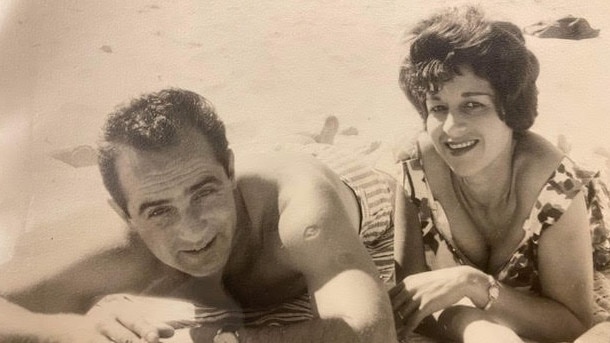

Yasha married my sister Cesia not long after they both had arrived in Australia, two young Holocaust survivors, he handsome as heck and Cesia vivacious and lively and beautiful despite what she had been through.

I described how when I was a child, perhaps eight years old, Yasha, then a young man ready to fight anti-Semites at the drop of a hat, powerfully built, with forearms like tree trunks in my mind’s eye, took me to the banks of the Yarra River near Melbourne’s CBD where each Sunday afternoon, the retailers of conspiracy theories of every kind shouted their stories, often to jeering crowds. Yasha went there not to listen but to beat up Nazis and in that, he was mostly successful.

Perhaps a week before he died on Saturday, I had come to see him and I had read him the piece I had written about him. At the centre of it was my admiration and love for him but also a sort of fear of violence I always felt when we were heading to the Yarra Banks – and he cried.

He took hold of my arms and dragged me to him and his strength surprised me and he said “thank you” in a whisper and kissed my cheeks and his embrace was firm even if his breath was weak, and I felt he was determined to keep on living for as long as possible and that he was still in the thrall of life, as if despite all the inhumanity he had witnessed and been subjected to, life was incomparably better than the alternative.

He was not ready to die.

His funeral was on Tuesday but Cesia, who is in a care home and who at 94 is physically in comparatively good shape but who has progressively slipped into a world that is inaccessible, was not at the funeral. She too has Covid.

I wish I could access her world even if only for a few minutes so that I could tell her that Yasha was a hero of the Jews and that so was she and that she had lived a life that encompassed so much of what life could bring and what life was for people like her. What I would not tell her was that in our family, she was the only one still alive to bear witness to what had happened to the Jews in those six years of World War II but that she was no longer able to tell her story in any coherent way.

For our family, finally, the Holocaust had slipped into history. For most of my life, it had been a living presence. I was raised by survivors and survivors married into my family – and I married someone whose mother had survived Auschwitz.

Now, with Yasha dead and Cesia living somewhere beyond my understanding, the Holocaust, even for me, will slip into history and history – its meaning and its lessons – are always increasingly contested. Yasha’s dying feels like a painful and a terrible confirmation of the end of something.

For several decades after 1945, the Jews could imagine that given all that had happened to them, perhaps anti-Semitism was at an end. And for Jews like me, raised in Australia or North America or Britain – and even in most of Europe – it did feel as though anti-Semitism had been consigned to history, to the increasingly distant past. In that world, anti-Semitism was shameful and unacceptable.

I think diaspora Jews like me thought the time of widespread anti-Semitism and overt Jew hatred would not, could not, ever return. I grew up feeling that Jews in places like Australia were admired. Jews had rebuilt their lives after the horrors they had been through.

They threw themselves into Australian life – in business, in law, in medicine, in the arts. They loved Australia and Australians, and Australia and Australians loved them back. That’s what I felt growing up and I think it was true up to a point, and certainly politicians of the right and the left regularly expressed admiration and even love – Bob Hawke, for instance, loved them – for Australia’s Jews.

That time of admiration and affection for the Jews that we felt would last forever, with anti-Semitism vanquished except in the metaphorical caves where the neo-Nazis lived, is over. I wrote about this in my book, My Life As A Jew, about how that post-Holocaust era –―which, if I wanted to be crass, I could call the post-Holocaust honeymoon for the Jews – was coming to an end. My book was published two days before October 7, two days before the Hamas terrorists’ slaughter and the kidnapping of hundreds of hostages and the war against Hamas in Gaza with the tens of thousands of civilian casualties.

I do not want to turn away from the horror of what the war against Hamas has meant for the people – men, women and children – of Gaza. I do not want to minimise the suffering and the deaths. But in the context of what I am writing here, apportioning blame for this catastrophic war – and the time for that will come – would deflect from this fact: before the IDF bombing campaign began, before the Israeli military response to the slaughter and the kidnappings, around the world – and particularly in the Anglosphere – there was an explosion of hostility towards Israel, Zionism and Jews. That was the response from much of the left to the October 7 pogrom.

October 7, in the most dramatic fashion, marked the end of the post-Holocaust era in which I grew up and in which I had lived most of my life. And Yasha’s death for me was a vivid reminder that the Holocaust was slipping into history and that anti-Semitism had not been defeated with the defeat of the Nazis with their Jew hatred which had led them to murder millions of Jews.

A week ago, the Jewish Review of Books, a US-based quarterly, published a symposium, Before And After October 7. The participants, mostly well-known academics and writers, were asked what had changed for them as Jews after the Hamas pogrom, the biggest mass murder of Jews since 1945. All of them, in different ways, said that their understanding of the world, the world of the Jews, their world, had changed, drastically changed. They are different people, some from the left, some from the centre politically, some even from the right, but all write as if they have been through a shared trauma, a shared realisation.

Anthony Julius is a professor in the law faculty at University College in London and is the author of Trials of the Diaspora: A History of Anti-Semitism in England. It is a terrific book. In the symposium, he describes how October 7 and its immediate aftermath changed him, how he came to understand that anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism were different forms of Jew hatred that were closely connected. He understood that he was wrong to think that “certain words and actions, certain defamations and atrocities” would be widely condemned, even by people who did not much like Jews. He had thought that Jews could rely on institutions―like the BBC to protect them and stand up for them.

“From a British perspective,” he writes, “the greatest disappointments have been the universities, the police and the BBC. They have shown Jews a very cold, hard face. The universities prompted least surprise, the BBC the greatest surprise.’’ Julius ends his piece saying he had come to understand that “the post-war period, in which Jews enjoyed relative security, was utterly anomalous”.

This view is widely held by Jews in the diaspora. It is widely held and felt in Australia. I think it is incontrovertible that Jews feel less safe, and are less safe, than they were before October 7. More than that, they feel less admired, and less loved. They feel like they belong to a vulnerable minority. They feel like the notion of powerful Jews manipulating politicians and journalists – a notion that has obsessed the ABC’s John Lyons for a long time, for instance – is laughable and disturbing. Such notions about Jews have a long and troubling history. I am not talking here about his reporting or his analysis some of which I might disagree with, but this is not what concerns me about Lyons and other journalists obsessed with what they perceive to be Jewish power.

That obsession leads Lyons to describe a WhatsApp group of Jewish lawyers – most of them junior lawyers, who called themselves lawyers for Israel – agents of a foreign government. And what had they done to deserve this terrible accusation, an accusation that smacked of the charge of Jewish dual loyalties? They had written letters to the chair of the ABC and to the managing director of the ABC calling for the dismissal of a casual presenter who they argued had posted on her social media virulent anti-Israel propaganda, including the accusation that IDF soldiers were raping Palestinian women.

It is beyond me to understand how a journalist would think this constitutes acting as agents of a foreign government rather than a group of Australians exercising their right to complain about the perceived bias of an ABC presenter.

There is less and less empathy for Jews, especially on the left, and because I have been a journalist for most of my life, it is most strikingly true of many journalists. In much of the reporting, there has been little sustained empathy for the Jews. There was no more than fleeting empathy for the Jews in the reporting of the Hamas massacres on October 7. And apart from a sort of grudgingly dutiful reporting, there has been little empathy for the hundreds of hostages, including old people and children, taken into Gaza by the Hamas invaders of southern Israel. And there has been a coldness, a chilling underplaying of what happened in the reporting of the mass rapes and the most indescribable sexual violence perpetrated against girls and women in southern Israel on October 7.

And at times there has been a shocking hardness on display. A few days after the October 7 massacres, Tom Joyner, the ABC’s correspondent, labelled reports about babies being beheaded by Hamas as “bullshit”, a disgraceful comment from a journalist which, for some people, called into question, cast doubt on, everything that the Hamas terrorists had perpetrated –―the murder of children in front of their parents, of parents in front of their children, of women raped and burnt after they were murdered, among other unspeakable horrors.

I don’t think Yasha, the warrior for the Jews, ever bought the notion that anti-Semitism or even dislike of the Jews had been beaten when the Nazis were defeated, and the world became aware of what had been done to the Jews. He loved life and he loved Australia, and he loved Australians, but he never believed the Jews would ever live in a world in which Jew hatred had been extinguished.

Michael Gawenda is a former editor of The Age and is the author of My Life as a Jew.

Yasha died last Saturday night. I was not there when he died. No one was there because he had caught Covid last week and had been taken to the Covid ward where he was allowed only two visitors for an hour each day and there were no exceptions to this rule, even for the dying.