Gadflies stood up to their party for sake of their state

The South Australian Liberal Party lost two people of great principle this week.

The South Australian Liberal Party lost two people of great principle this week.

The first was so principled that he knowingly led his party to defeat by tackling one of the greatest electoral rorts seen in Australia.

The second was so principled that she was admonished for her outspokenness, her subsequent sidelining setting up a state for the greatest economic calamity it would face.

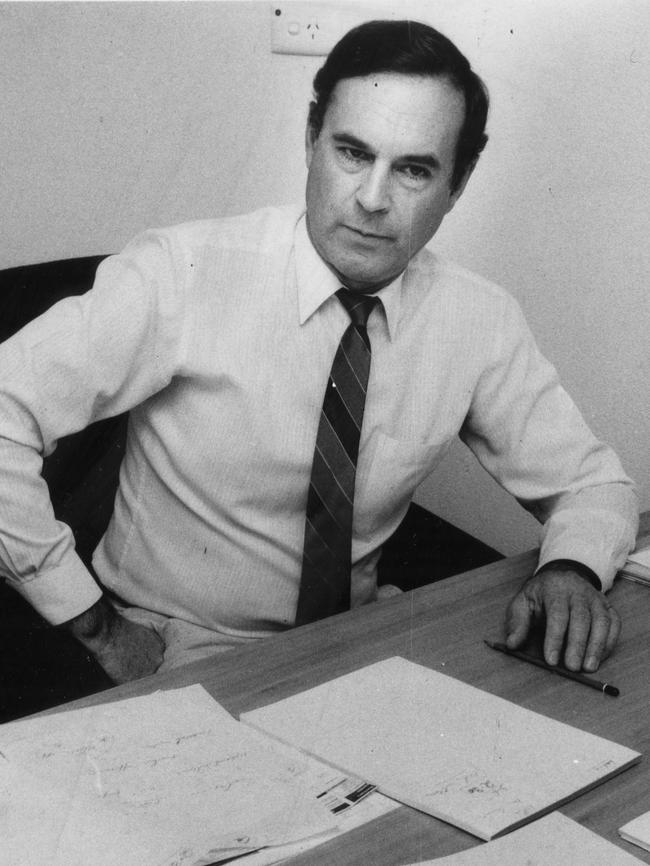

The first is former South Australian premier, senator and MHR Steele Hall, who split from the Liberals and founded the breakaway Liberal Movement in the 1970s. It was a calamitous schism, the effects of which still can be seen today in the factionalism that marks conservative politics.

It also gave rise to the creation of the Australian Democrats and turned the moniker “small-L liberal” into a household term, as Hall pitched himself as a freethinker who stood apart from Malcolm Fraser in refusing to block supply in the 1975 constitutional crisis, and later joined Philip Ruddock and Ian Macphee in repudiating John Howard over his call to reduce Asian immigration in the 1980s.

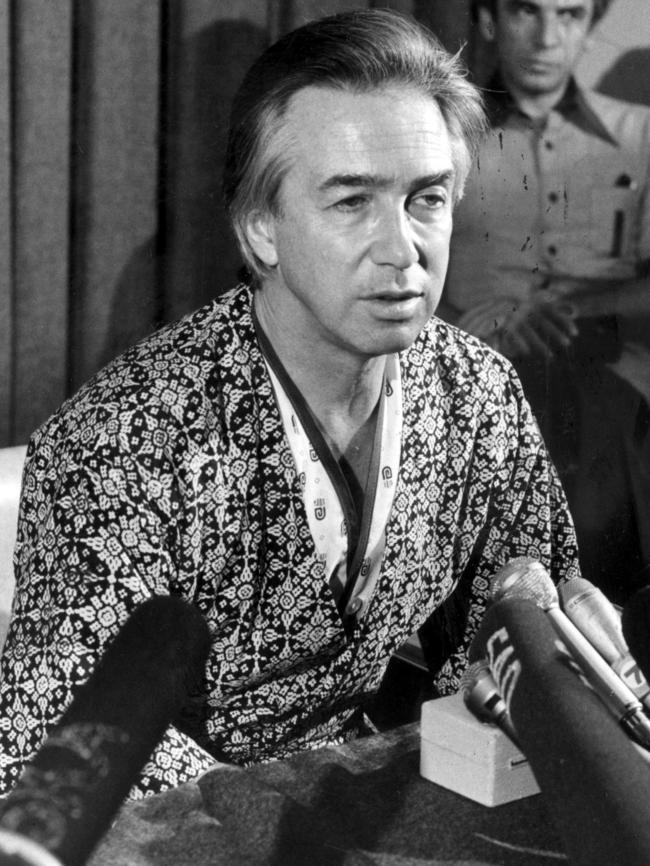

The second was a lesser-known figure outside SA, the heroic Jennifer Cashmore MLC, the first South Australian MP to start probing the finances of the State Bank of South Australia ahead of its $3.15bn collapse in 1991.

The scale of that collapse was immense at the time and fuelled years of cargo-cultish politics in SA, this impecunious state lumbering itself with a can-rattling reputation with endless calls to save manufacturing jobs and create made-up new ones to offset the bank catastrophe. In the aftermath of the bank’s collapse young university-educated South Australians left the state in droves and many never returned.

Cashmore’s hunch, framed on sound intelligence, was that the government-backed bank was headed for the wall weighed down by non-performing assets and excessive loans.

Cashmore was 100 per cent right, but she was warned off her pursuit by a nervous state Liberal leadership for fear of talking down the state. She later estimated that had the bank’s parlous state been addressed when she first raised it, the impact of its losses could have been limited to $1bn.

In a melancholy coincidence, Hall and Cashmore died peacefully within hours of each other in Adelaide on Monday. Hall was 95, Cashmore was 86.

In the 1960s the dashing Hall emerged as the anointed successor to Thomas Playford, who by the length of the straight remains Australia’s longest serving premier, governing SA for 26 years and 125 days, a full seven years longer than Joh Bjelke-Petersen in Queensland. Playford notched victories in 1941, 1944, 1947, 1950, 1953, 1956, 1959 and 1962. He did so for three reasons – his austere everyman style, his transformation of the agrarian-dependent SA economy into a manufacturing powerhouse, and an electoral system so profoundly unfair it made it almost impossible for Labor to win.

Despite hailing from rural Balaklava, Hall was aware of and embarrassed by an electoral system that valued country voters over urban voters by a factor of up to 10 to one. Although the vast bulk of SA’s population lived in Adelaide, the SA lower house comprised 39 seats of which only 13 were suburban and 26 were in country SA.

When Hall was elected premier in 1968 at the height of what became known as the Playmander, the northern suburban seat of Enfield had 42,000 electors while the country seat of Frome had just 4500. With the Liberals forming office with barely 40 per cent of the two-party preferred vote, and Labor consistently losing despite winning several absolute majorities, there were growing protests in SA about the unfairness of it all.

Hall sensed the mood and as premier implemented a program of electoral reform that evened the ledger. Despite the move being backed by city Liberals and some country members who could see the crookedness of the system, many in what was then known as the Liberal and Country League regarded Hall as a pariah who had set his party up to fail.

Mount Gambier-based conservative Renfrey Curgenvon DeGaris never forgave Hall, nor did others from the party’s conservative rural constituency, and when Don Dunstan was elected Labor premier in 1970, the Liberals were riven by infighting over the impact of Hall’s reforms.

In 1972 Hall finally quit to form the Liberal Movement and remained in state parliament for another two years before winning a Senate spot as a Liberal Movement candidate at the 1974 federal election. The small-L liberal politics of the Liberal Movement were epitomised by its slogan, “Leave the Extremes”, but Hall remained a Liberal Party man at his core and when the party reunited in 1976 he rejoined straight away.

By the time he vacated the Senate in 1977 to contest the federal SA seat of Hawker, the Liberal Movement had merged with and been renamed the Australian Democrats, with its future leader Janine Haines appointed by the Dunstan government to fill Hall’s Senate vacancy.

Despite losing in Hawker, Hall made an emphatic return to federal politics in 1991 by winning Boothby, where he remained the local member until retiring at the election of the Howard government in 1996.

There is a sense that Hall is regarded as the “moderate’s moderate” and the more progressive members of the party were quick to praise him and his legacy with his death this week.

Opposition Senate Leader Simon Birmingham hailed Hall as “a reformer, an orator and a man of principle willing to stand by his values”. “Many will rightly remember Steele’s principled and ultimately self-sacrificing leadership as the premier who oversaw important electoral reforms to deliver one vote, one value in SA,” Birmingham said.

But Hall has enjoyed equal generous praise from staunch party conservatives including veteran senator and Howard era minister Nick Minchin, who says Hall should be remembered not as a wet or a dry but a freethinker.

“Steele was a stickler for propriety,” Minchin tells Inquirer. “He was a true Liberal in most of his views but, more than that, he really loathed expediency. If that meant he thought blocking supply was wrong, he would refuse to do so.

“He was an independent thinker. And even though he was pilloried by some for his electoral reforms as writing our own suicide note, he knew the system was wrong and had to change, meaning the subsequent schism was probably inevitable.”

Unlike Bjelke-Petersen, whose grip on power was tightened by an equal questionable electoral distribution, the Playmander was undone in South Australia by Hall’s political decency. In Queensland Bjelke-Petersen left kicking and screaming, his government mired in scandal, still regarded as a laughable affront to democracy.

But to this day there are some in the Liberal Party in South Australia who wonder if, by Hall’s attempt to address the electoral imbalance, Labor became the new beneficiary with a swath of suburban seats, many of them blue-collar and with high numbers of public servants, leaving the Liberals resembling a rural rump.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout