Fusion success serves only to highlight energy challenges

US scientists’ breakthrough has profound implications, but most of us won’t be around to see them.

Mastery of nuclear fusion, the process that underpins the sun and stars, foreshadows endless energy without toxic waste or carbon dioxide emissions.

Researchers at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California revealed they had produced more energy in an experimental nuclear fusion reaction than was required to start the process. Dr Warren McKenzie, founder of Australian laser nuclear fusion company HB11 Energy, hailed the result of the experiment as being “as significant to the global energy industry as the first moon landing was for the space industry”.

“This ‘holy grail’ scientific milestone has far greater implications for the world at large, given it finally unlocks the prospect of unlimited clean energy,” he added, reflecting an excitement that ricocheted around the world.

It does have profound implications, but most of us won’t be around to see them.

Much-deserved praise for the achievement must stop short of any sense of relief we have solved the energy conundrum of our age – how to power the world without fossil fuels.

The gap between the development of the first steam engine and commercially viable trains, between the internal combustion engine and mass-produced cars, was many decades.

And this time will be no different, Mark Mills, a physicist and energy specialist at the Manhattan Institute, tells Inquirer.

“The joke among physicists is that fusion is always 50 years away; maybe it now actually is 50 years away but that’s no help for 2050 goals,” he says.

Fusion is difficult to pull off: scientists need to combine two atoms together, possible only at immense temperatures, a process that produces excess energy.

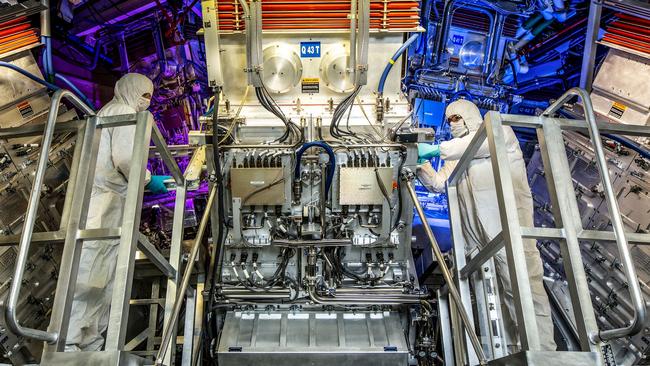

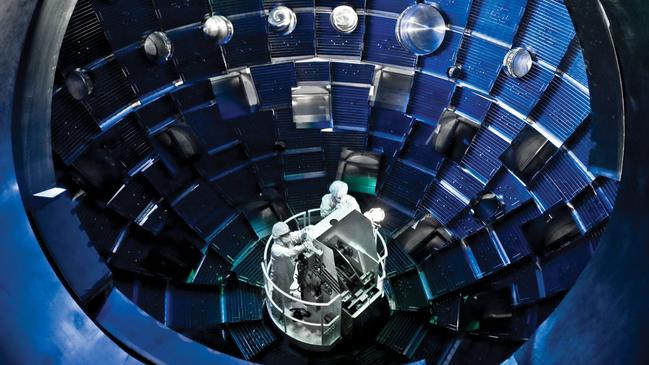

“This was a very valuable tabletop demonstration, but the table cost $3bn, was 500ft (152m) long and seven storeys high, housing a laser that would make the laser in the original James Bond Goldfinger look like a child’s toy,” Mills explains, pointing out that the ratio of energy produced to energy required must be many thousands in order to be commercially viable.

In the successful experiment on December 5 at the laboratory’s National Ignition Centre, scientists produced a little over 3 megajoules of energy from two megajoules, for the first time achieving a better than “break even” result.

“Each of those pellets, about the size of an eraser, cost about a million dollars each to make, we’d have to make millions of them a year … And the laser can fire a few times a day at most, we’d need one that can fire 10 times a second,” Mills says.

He says a good analogy is putting man on the moon in the 1960s: “It cost billions, was certainly technologically remarkable, but putting all of mankind on the moon sustainably? – that’s what we’re talking about here.”

Net-zero advocates will use the US development to push the “anything is possible” idea with further investment.

But if anything, the latest progress on nuclear fusion should signal the need for humility, a reminder that lofty, widespread hopes for imminent improvements in battery technology are unrealistic.

The political desire for net zero by 2050, however strong and widespread, can’t change the laws of nature, or the fact that battery technology remains woefully inadequate to compensate for the intermittency of solar and wind power.

Even jurisdictions further advanced on the transition, from Germany to Tasmania’s King Island, need to maintain costly fossil fuel back-up plants for periods of inclement weather, which can last many days.

The US would require 1.55 million of the massive batteries currently being constructed in Queensland by Vena Energy, which can store 150 megawatt hours of power. That would cost tens of trillions of dollars, according to a 2022 analysis by Francis Menton for the Global Warming Policy Foundation.

“It is abundantly clear that no jurisdiction can get anywhere near net zero on the current path of just building more wind and solar generators and paying little to no attention to the problem of energy storage,” he says.

The relentless push to replace coal, gas and nuclear with solar and wind power come what may, hoping that battery technology improves enough along the way, is a bit like jumping out of a plane and hoping a parachute is invented on the way down.

Throughout history, only advances in computing and digital technology have galloped ahead quickly, while everything else has been quite slow, as a perusal of any of economist Robert Gordon’s writing would reveal.

Germany is frantically building LNG terminals, Japan is switching coal-fired power plants back on, and France is desperately trying to fix its ailing nuclear power plants.

Politicians’ relentless reassurance that renewable energy means cheaper power for the end user is looking more ridiculous all the time.

The wheels are coming of the net-zero bandwagon, and nuclear fusion and commercial scale won’t arrive in time to save it.

The voting public soon will begin to realise maintaining their standard of living – or, for developing nations, seeing any improvement – requires fossil fuels and traditional nuclear power as a large share of the energy supply mix.

The US scientists’ latest success with fusion at least should broaden the public’s focus on future energy supply possibilities, helping to improve the irrationally tarnished public image of nuclear power more generally.

US businesses seeking to take fusion forward have raised more than $US5bn ($7.3bn) in private funding, around twice the level of a year ago according to The Wall Street Journal, a fine improvement but still a tiny fraction of the hundreds of billions spent annually around the world on new renewable power supply.

The West is rapidly ceding expertise in nuclear technology to China, which can already build new nuclear fission reactors at a fraction of the cost and time of US and European manufacturers.

“This (US) result will put a rocket under a new industry of high-power lasers and inspire billions to be invested in laser fusion energy,” says Mackenzie, whose HB11 Energy announced this week its plan to build a high-intensity petawatt-class laser facility on Australian soil.

Australia isn’t too small to help the US maintain its nuclear technological edge over China

Mackenzie says it was an Australian, Sir Mark Oliphant, who demonstrated nuclear fusion in 1931.

The world of physics was brought to a standstill this week after US scientists announced they had, in a world first, pulled off a nuclear fusion reaction – the elusive, perfect cousin of nuclear fission that was pioneered decades ago.