Frustrating path to justice after Bali bombings

After almost two decades of political and legal wrangling, the Bali bomb mastermind will finally face justice.

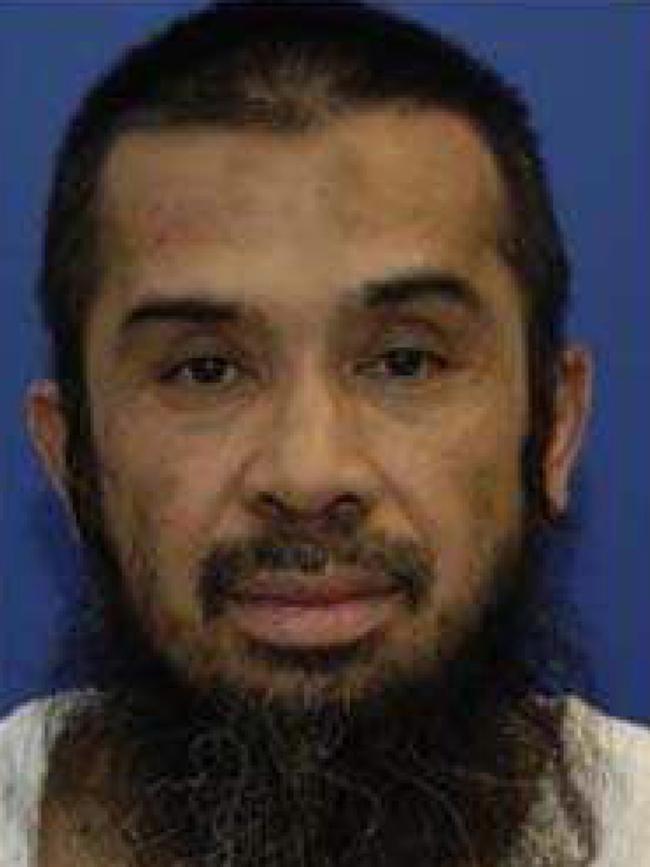

Eighteen years after Southeast Asia’s most wanted terrorist, Hambali, was arrested in Thailand, the Indonesian-born mastermind of the deadly 2002 Bali bombings and 2003 Jakarta Marriot bombing is finally to stand trial in a closed US military court.

The 56-year-old terrorist, a close associate of 9/11 al-Qa’ida mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and Jemaah Islamiah founder Abu Bakar Bashir, and a key interlocutor between the two terror groups, will be tried alongside two Malaysian citizens before a military jury on the US naval base in Cuba.

“The charges include conspiracy, murder, attempted murder, intentionally causing serious bodily injury, terrorism, attacking civilians, attacking civilian objects, destruction of property and accessory after the fact, all in violation of the law of war,” the Pentagon said in a statement on Thursday.

The announcement was made on the first full day of the Biden administration, but the decision is understood to be one of a number of 11th-hour moves by the outgoing Trump administration to lock in the Republican preference for military over civilian trials for high-value terror detainees.

The Obama administration, in which President Joe Biden served as vice-president, sought unsuccessfully to have them tried in civilian courts.

James Valentine, a Marine lawyer and long-time defence counsel to Hambali, accused US military officials on Thursday of acting “desperately in a state of panic before the new administration could get settled”. He claimed the “torture regime hit the panic button after yesterday’s inauguration”.

Major Valentine has for several years lobbied for Hambali to be extradited and tried in Indonesia, insisting he cannot get a fair trial in the US because of CIA concerns over keeping details of his rendition and torture secret.

The Indonesian government would not comment on the issue on Friday, though Jakarta-based terrorism expert Sidney Jones says Indonesia is unlikely to want Hambali back under any circumstances.

“They have not been pushing for this trial or anything that would in any way speed up the process of his repatriation,” she tells Inquirer.

Born in Cianjur, West Java, as Encep Nurjaman in April 1964 but now universally known by his nom-de-guerre, Hambali was a highly trusted mediator between al-Qa’ida and Indonesia’s Jemaah Islamiah network.

“Hambali was extremely significant as the person who basically decided that al-Qa’ida’s exhortation to wage war, wherever and however you can, against the Christian-Zionist alliance had to be translated into a plan of action for Indonesia,” says Jones.

“And then he made it operational with the funding. He was in direct communication with Khalid Sheikh bin Mohammed and some other leading lights of al-Qa’ida.”

The massive bombs that ripped through Paddy’s Bar and the Sari club in Bali’s nightclub district on October 12, 2002, still rank as Indonesia’s worst-ever terror attack. Twelve people were killed the following year in the Jakarta Marriott Hotel bombing, and as many as 150 people injured.

Eighty-eight Australians were among the 202 people who died as a result of the Bali blasts for which three JI operatives — Imam Samudra, Amrozi Nurhasyim and Ali Ghufron — were executed by firing squad.

Their Indonesian trials, and that of their spiritual leader, Abu Bakar Bashir, were closely followed in Australia, where news of Hambali’s trial will be welcomed.

But Melbourne man Jan Laczynski, who lost five friends in the 2002 Kuta bombings, says he too would have preferred to see Hambali tried in Indonesia.

“As painful as it is for survivors and friends (of victims), it should be held with full media reporting,” he tells Inquirer. “If it was conducted in Jakarta or Bali it may even have been well attended. There is no way we would have accepted the Bali bombers’ trial in secret.”

News of Hambali’s trial comes less than a fortnight after the Indonesian government released Abu Bakar Bashir. The 82-year-old hardline cleric and JI founder served close to a decade behind bars for supporting military training camps.

Bashir was also arrested in the wake of the 2002 Bali blasts and initially found guilty for his role in the attack, alleged to have been one of spiritual guidance for the bombers and green-lighting of their terrorist plot, but his conviction was overturned on appeal.

He ultimately served just 26 months for immigration violations and supporting a terrorist training camp.

Hambali, meanwhile, was detained in August 2003 in Thailand in a joint Thai-US intelligence raid along with two Malaysian men, Mohammed Nazir Lep and Mohammed Farik Amin, whom the Pentagon alleges were top JI aides trained by al-Qa’ida.

The men spent three years in the CIA’s “rendition and interrogation” program, moved between CIA black sites in Afghanistan, Poland and Jordan, and subjected to what a damning US Senate report in 2014 revealed included torture such as waterboarding, beatings, extended periods of nude shackling and stress positions. Hambali was also alleged to have been subjected to a technique known as “walling”, in which a collar was placed around his neck during interrogation and his head repeatedly slammed against the wall.

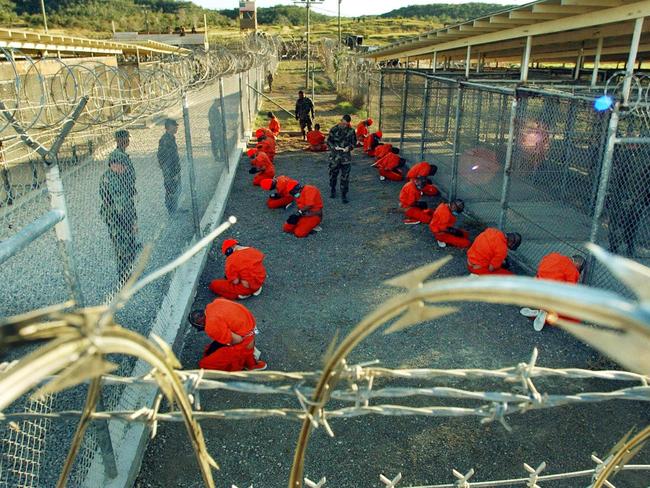

All three have been held in Guantanamo since 2006 and lawyers for Hambali are expected to rely heavily on his years of torture in their defence. Rumoured to be among potential witnesses is Australian man Jack Roche, who plotted with Hambali to attack Israeli targets in Australia before seeking to turn himself in.

Charges against Hambali, whom the Pentagon describes as the leader of JI and a top al-Qa’ida representative in the region, were first laid in 2017, but approval for a trial was resisted until this week. If he is convicted, Hambali will most likely remain in Guantanamo.

Quinton Temby, a Singapore-based Southeast Asia terror analyst and author of the upcoming Subterranean Fires; the Rise of Global Jihad in Southeast Asia, says Hambali was not only an influential player in regional militant circles but a key figure in the rise of global jihadism.

“He was the most important terrorist in Southeast Asia at the time and had a very close relationship with Khalid Sheikh bin Mohammed that was central to the whole al-Qaeda wave of attacks around 9/11,” he tells Inquirer.

Hambali was also central to a foiled al-Qa’ida plot to follow the 9/11 attacks just months later with a second aeroplane-based attack on the US west coast, carried out this time by Southeast Asian terrorists.

So why has it taken so long to bring him to trial?

Zachary Abuza, a Southeast Asia security expert with the US National War College, says successive US administrations have struggled with how to proceed with trials, which is why there are up to 20 high-value terror detainees still in Guantanamo Bay, including Khalid Sheikh bin Mohammed.

“They have spent 18 years trying to figure out how to ‘clean sheet’ this process. That’s been an issue. The use of torture has been an issue, the question of the legality of military trials has been an issue,” says Professor Abuza.

“If this was easy it would have happened years ago.

“I can’t tell you the number of military prosecutors and defence lawyers who have quit out of frustration over the proceedings. We really don’t know what happens with the whole issue of waterboarding and other tactics that can only be described as torture, and how a court will handle this.

“I don’t think they have really yet figured out the whole issue of how they can use classified information, and not share it with the defence. All these things have just thrown incredible doubt into the process. I mean, here we are in 2021 (laying charges) for a crime Hambali committed in 2002.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout