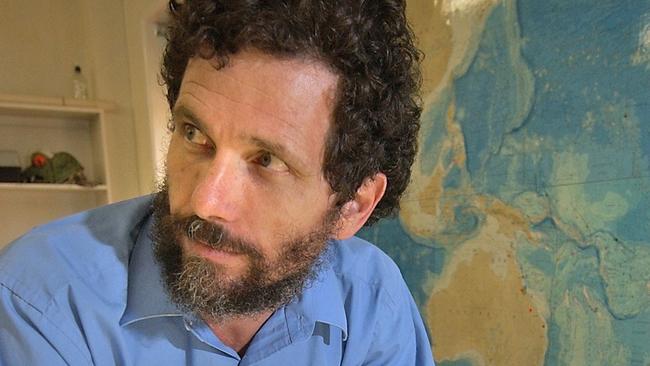

Peter Ridd: Free to defy higher education orthodoxy

Peter Ridd’s win against James Cook University has touched a raw nerve about the health of academic freedom of speech.

Throughout his ordeal with James Cook University, contrarian physics professor Peter Ridd has not lost his sense of humour.

Ridd is particularly amused by complaints from JCU that he had accused it of being “Orwellian” in its treatment of him during a protracted disciplinary process.

How did the university know Ridd thought its actions to be Orwellian?

It knew because JCU powers had trawled through all of Ridd’s personal emails in a hunt for dirt on the former head of physics, who also had managed the university’s marine geophysical laboratory for 15 years.

After reading his emails, JCU slapped Ridd with a new charge of ignoring a “no satire” direction when it discovered he had sent a newspaper cutting from The Australian to a former student with the heading “for your amusement”.

Responding to the new charge, Ridd said at the time: “If I am going to be sacked for anything, I want it to be for that.”

Ridd has been an outspoken critic of the quality of scientific research on the Great Barrier Reef, saying its health has often been misrepresented.

Billions of dollars of public funds are being spent without a proper evaluation of the science on which the decision-making is based, he has argued.

JCU sacked him for his Orwellian comment, his satire and a long list of other claimed breaches, but this week the Federal Court found his termination to be unlawful.

JCU executives have blasted the judgment and the Ridd case seems far from over. Nonetheless, the win has been celebrated around the world. It has touched a raw nerve about the health of academic freedom of speech.

Recent cases include the treatment of a Griffith University lecturer who will leave the institution after a Facebook complaint over her discussion of missions during an indigenous studies class, even through she said the complaint was factually incorrect.

In the US, well-known academic Camille Paglia is facing a petition that she be fired from her tenured position at University of the Arts for daring to have a dissenting view on how best to accommodate transgender individuals and handle cases of sexual assault.

In his independent review of freedom of speech in Australian higher education providers, former chief justice Robert French notes that discussion of the issue is hardly new. He quotes prime minister Robert Menzies in a 1964 speech: “The integrity of the scholar would be under attack if he were told what he was to think about and how he was to think about it.

“It is of the most vital importance for human progress in all fields of knowledge that the highest encouragement should be given to untrammelled research, to the vigorous pursuit of truth, however unorthodox it may seem,” Menzies said.

French’s principal recommendation is that protection for the freedoms be strengthened within the sector on a voluntary basis by the adoption of umbrella principles embedded in a code of practice for each institution.

The French recommendation comes after the event for Ridd but is actually central to the decision of Federal Court judge Salvatore Vasta. The judge found that Ridd was protected by a provision on academic freedom that overrode other provisions of the code of conduct.

Ridd was sacked after the university concluded his behaviour demonstrated “repeated denigration of the university, insubordination, interference with the disciplinary process, denigration of colleagues, noncompliance with the code of conduct and a lack of respect for confidentiality”.

In court, JCU argued there could be “no comfort in authorities in the United States that deal with the concept of intellectual freedom” because Australia had no underlying constitutional right to freedom of speech as expressed in the first amendment. Vasta was at pains in his judgment to emphasis the Ridd case was not about freedom of speech and intellectual freedom, academic conduct, polite language or the silencing of inconvenient views, although those issues had been canvassed.

Rather, the trial was purely and simply about the proper construction of an enterprise agreement; whether a clause on “intellectual freedom” overrode others in the JCU employment contract.

Nonetheless, the judge said the concept of intellectual freedom was extremely important because it helped to define the mission of any university.

“Whilst it might not be a fundamental right,” Vasta said, “it is nonetheless the cornerstone upon which the university exists. If the cornerstone is removed, the building tumbles.

“That is why intellectual freedom is so important. It allows academics to express their opinions without fear of reprisals. It allows a Charles Darwin to break free of the constraints of creationism. It allows an Albert Einstein to break free of the constraints of Newtonian physics.

“It allows the human race to question conventional wisdom in the never-ending search for knowledge and truth.

“And that, at its core, is what higher learning is about. To suggest otherwise is to ignore why universities were created and why critically focused academics remain central to all that university teaching claims to offer.”

The Institute of Public Affairs, which supported Ridd through the trial, says the judgment is “a huge win for academic freedom and for freedom of speech in Australia”.

IPA director of policy Gideon Rozner says JCU’s actions prove the depth of the free speech crisis confronting Australia’s universities. “Australian universities must now commit to signing up to the model code as recommended by Robert French in his review of freedom of speech at Australian universities,” Rozner says.

JCU has been quick to protest against the Vasta judgment but no decision on whether it will appeal has been made public.

Immediately after the judgment, vice-chancellor and president Sandra Harding sent a message to JCU staff in which she said the university had not taken issue with Ridd’s right to academic freedom.

“The judgment does not refer to any case law, nor any authority in Australia to support its position,” Harding said. She said Ridd was not sacked because of his scientific views.

But Vasta said JCU had “played the man and not the ball”.

“Incredibly, the university has not understood the whole concept of intellectual freedom,” Vasta said. “In the search for truth, it is an unfortunate consequence that some people may feel denigrated, offended, hurt or upset.

“It may not always be possible to act collegiately when diametrically opposed views clash in the search for truth.

“The university has denounced Professor Ridd because his enquiry, examination, criticism and challenge was not, in their view, done in the collegial and academic spirit.

“But there is no need for such enquiry, examination, criticism or challenge to be done that way under the rights conferred upon Professor Ridd by the clause 14 which gave his academic freedom.”

Ridd says the judgment should put a big cloud over the future of senior JCU administrators.

For a lifetime academic, Ridd says there have been many lessons from the ordeal, which has made a big impression in north Queensland. “I am being stopped in the street. I don’t know these people from a bar of soap but they are concerned about what has happened,” he says.

But even for someone used to controversy, it has been “incredibly stressful” and full of risk.

Ridd was able to pursue the legal action against JCU only because of the hundreds of thousands of dollars that were raised internationally through a GoFundMe initiative.

“When we did the GoFundMe, we thought we might just get $500 and I would be fired for putting everything up on the website (documenting his case),” Ridd says.

But after a few hours, the money started gushing from people around the world concerned about what has been happening at universities globally.

“Words escaped me,” Ridd says. “It was not just the money coming in but the comments that were being left by donors.

“People just said this really smelled and that there was a bad thing happening.”

Ridd laments the changing fortunes of his profession. He says universities are not the way they were 30 years ago when a professor carried weight.

“Professors are not important people any more — they are there to be obedient to administrators,” Ridd says.

And he remains unsure about what the future holds. “I am not sure what I want at the moment,” he says.

A hearing will be held later to determine what the remedy should be for Ridd’s illegal sacking by the university.

“I love the university and want to go back in some form but I don’t see how that will be possible with the existing VC.”

Ridd says he has been most heartened by the support from professional adversaries.

“One of the biggest things is my arch-enemy in scientific argument (JCU colleague) Jon Brodie, said on radio that what JCU had done to Peter Ridd was disgraceful,” he says. “My most virulent scientific opponent had spoken out in my support.”

This, Ridd says, is a true measure of academic freedom.