Free thought at stake in the New Inquisition as gender-critical feminists, climate-change sceptics demonised

You might see one left behind on a church pew or on a bookshop shelf. Pick it up. Flick through its pages. And wonder how this tiny tome came to be.

For these books were given to us by heretics.

The sacrifice and bravery it required to invent a small Bible in one’s own language is unimaginable to our 21st-century minds.

It was over the dead bodies of dissenters – literally – that these books were born.

Consider William Tyndale, one of the great rebels of English history. He was a biblical scholar who lived from 1494 to 1536. He was an early Protestant reformer. And he devoted his life to doing something that was punishable by death – translating the Bible into English.

Back then, the Bible was in Latin. Biblical knowledge was for learned men only, those well versed in the Latin language.

As FL Clarke put it in his classic 19th-century biography, The Life of William Tyndale, the authorities believed only “good and noble” men should have ready access to the holy book.

They believed that “for the Bible to be placed in the hands of the common people was a dangerous thing”.

The “poor and ignorant” were seen as sheep, Clarke wrote, who should content themselves to hear only those parts of the Bible that their moral superiors read out in church on Sunday.

Tyndale set out to up-end this moral order. To turn the world on its head.

There had been English-language Bibles before, most notably Wycliffe’s Bible, produced by radical theologian John Wycliffe in the late 1300s.

But the tumult caused by that book – especially its stirring up of public agitation with the Catholic authorities – led to a severe clampdown on biblical translation.

By Tyndale’s time, death by fire awaited any man foolish enough to make an English Bible.

Tyndale was willing to take that risk. Unable to print his native-tongue Bibles in England, he travelled to Germany, where Martin Luther’s German translation had appeared in 1522.

Tyndale’s English translation made its appearance in Cologne in 1525.

He spirited the sinful tracts back to Britain, hidden in cargoes of grain, where his supporters would distribute them among knowledge-hungry radicals.

They were dicing with death by reading the Bible. Tyndale’s books were “copied in secret and read in terror”, Clarke wrote.

Tyndale’s next move was to make a smaller Bible, one that could be easily carried about and speedily disposed of if the authorities came knocking.

And there it was: a kind of pocket Bible, born from the necessity of secrecy in an unfree world.

Tyndale was condemned as a heretic and hunted like an outlaw. Church authorities pursued him all the way to Germany.

In 1535 they got him. He was tried for heresy in 1536, convicted, strangled to death and burnt at the stake. “The mortal remains of William Tyndale were an indistinguishable heap of ashes!” Clarke cried in his biography.

This is what you should think about next time you see a small Bible, or any Bible in English: Tyndale’s life on the run; his clandestine writing; his execution.

Not to be morbid. No, just as a reminder that virtually every liberty we enjoy is a gift of heresy. A reminder that the incalculable courage of yesteryear’s “wrongthinkers” helped to make our lives freer and happier than they might otherwise have been.

Never take the Bible for granted again.

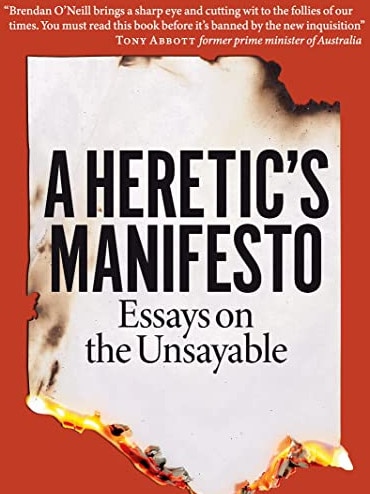

In my new book, A Heretic’s Manifesto: Essays on the Unsayable, I make the case for heresy. I argue that dissent, daring, scepticism and iconoclasm have been essential to social progress.

It is hard to think of any right we enjoy that was not born from the fires of heresy.

Consider 17th-century English radical John Lilburne and his idea of “freeborn rights” – that is, that every person has fundamental rights from birth.

Lilburne was persecuted for his various radical ideas. He was once marched along Fleet Street, being whipped as he went, so that his shoulders “swelled almost as big as a penny loaf with the bruises of the knotted cords”, as one contemporary account described it.

Yet his heresy is mainstream belief now, though we call them natural rights.

It was once heresy to say the Earth was not at the centre of the solar system. Now it’s science. Blasphemous thought expanded our knowledge of our universe.

Or think of those Enlightenment heretics who argued for freedom of religion. Or the working-class heretics who demanded the right to vote and who, in Manchester in England in 1819, were massacred for doing so. Or the suffragette heretics who took a metaphorical cudgel to every orthodox idea about the “fairer sex” when they proposed that women should have political rights, too.

All these ideas were profanities against the social order. Even uttering them was a risky business. Social ostracism, jail, even death sometimes awaited the blasphemous bearers of such dangerous thoughts.

Yet through the heretics’ perseverance, thinking changed, society progressed and what was once an outrageous notion became the bread and butter of public life.

This is what worries me about our tyranny of cancel culture.

As I argue in my book, the vibe of the witch-hunt is back, if not witch-hunts themselves.

Today’s demons are gender-critical feminists, climate-change sceptics, populists, those who bristle at the diktats of the supposed expert classes.

No, they are not whipped on Fleet Street. They are not pelted with rotten fruit. They are not set on fire. But their careers are. Their lives are.

People are being demonised, cancelled, hounded off university campuses, reduced to social lepers and sometimes sacked for challenging the new orthodoxies of wokeness.

In the absence of the right to think differently and speak freely, progress can stall. New ideas go undiscovered. Better ways of running society go unimagined.

It’s time to push back against the New Inquisition. Heretics, step up: say what you believe, whoever it offends. You might be damned as a blasphemer, but as George Bernard Shaw said: “All great truths begin as blasphemies.”

Brendan O’Neill’s new book, Heretic’s Manifesto: Essays on the Unsayable, is published by Spike.

The next time you see a pocket Bible, I want you to think about how such a book came into existence.