Forcing opinions on to others creates division, not diversity

Peter FitzSimons may have fame and money, but credibility is proving more elusive.

The italics are his. FitzSimons may have fame and money, but credibility is proving more elusive. FitzSimons’s call for a statement from the seven players sounds like a new inquisition where heretics are called to account for their different views.

One word should do. Faith. The italics are mine. In the hierarchy of what matters most, these seven players have chosen their faith above a rugby game. In a free country, they get to decide that, and how they express their faith, and what values they prize ahead of others provided they are not harming others.

Can you imagine what the former Wallaby would have said if the Manly Sea Eagles had told its players a day or two before the game that for this week only they would be wearing a Hillsong-themed jersey and be required to listen to the Lord’s Prayer instead of a Welcome to Country?

The decision by the Manly players may disappoint, offend, even hurt the feelings of many people. But their decision to quietly sit out a game rather than wear a rainbow jersey that was not raised with players, but foisted on them, does not harm anyone. Just as FitzSimons has his own faith, secular and woke though it may be, the rugby players have theirs. Just as FitzSimons may not always be consistent in his beliefs, the rugby players may also pick and choose what matters to them.

The difference is that the Manly players, most of them Pacific Islanders, and Christians, are not using their platform to insist that others agree with their values. They are sitting out the game. We have laws, in the Fair Work Act, to protect employees from discrimination by their employers on the basis of sex, sexual orientation, marital status – and religion.

There was a very different reaction when AFLW player Haneen Zreika, a practising young Muslim woman, refused to play a footy game for GWS wearing a jersey that celebrated a pride round.

The head of the AFL’s inclusion policy, Tanya Hosch, said that “People of faith have rights as well”.

“We want the game to be inclusive; you don’t get to choose to just pick and choose who represents inclusion,” Hosch said.

Back then, there was no thundering condemnation from FitzSimons. Though disappointed, he pointed out that Zreika is “quietly declining to use her platform to promote a belief she’s not comfortable with”.

Did FitzSimons give the young GWS player a pass because she is a woman and a Muslim? Is targeting Christian players the last acceptable prejudice? It’s hard to follow FitzSimons’s logic.

Diversity and inclusion are fine ideals in a free and fair society. But diversity and inclusion become hollow ends when imposing one set of views becomes the means. It is the phoniest form of diversity and inclusion.

Perhaps we will find more common ground when we recognise and respect diversity, rather than compel people to celebrate it. Reasonably, people may not be interested in celebrating the religious views of the seven Manly players. Equally reasonably, some committed Christians may recoil at being forced to celebrate homosexual pride.

Building a deeper, quieter form of respect, rather than forcing players to wear a pride jumper, may prove to be a more effective way to build genuine inclusion. It is less showy, to be sure, and it is also a two-way street. This path may foster more unity, a lasting tolerance for others, whatever their sexuality, gender, skin colour or religion, in a modern liberal democracy.

One thing is clear. Forcing people to celebrate diversity by putting on a rainbow jersey is no way to build genuine and lasting respect.

Diversity and inclusion have become the weapons du jour to discriminate against others, harass them, and even sack people with different views.

For seven years, British woman Maureen Martin worked at an organisation that provided local housing. She was politically active during that time, unsuccessfully standing for parliament a few times. When she stood in the mayoral elections this year, she was given a full page in the local mayoral booklet to set out her campaign beliefs.

Apart from wanting to tackle knife crime and advocating for lower taxes for local businesses, Martin – a woman of colour – said she wanted to promote marriage between a man and a woman as the fundamental building block for a successful society.

Martin told London’s Mail on Sunday that she was subjected to a “Soviet-style interrogation” about her beliefs by her employer L&Q over three complaints, and then sacked. In a letter, L&Q claimed that she had expressed her views in an inappropriate manner, and it was “reasonable to conclude that they will have caused upset, hurt and offence”.

Martin is suing L&Q for discrimination, harassment, and unfair dismissal. The message from her sacking is if you don’t line up with the new orthodoxy, you can lose your job.

There are signs of common sense. Earlier this month, a British tribunal found that Maya Forstater, the tax expert whose contract with the UK Centre for Global Development was not renewed because she said that biological sex is immutable, was unfairly discriminated against for her views. This decision is a far cry from an earlier one where a judge found that Forstater’s views were “not worthy of respect in a democratic society”.

In a free society, there are a plethora of rights. The right to express one’s views. The right to exercise one’s faith. The right not to be harmed by violent speech. The right not to be defamed by speech. The right not to be offended or have one’s feelings hurt by someone else’s views.

That last one has been gifted in more recent years by government in various laws. Understandably, this government project to protect hurt feelings is the precursor to modern organisations promoting diversity and inclusion.

But no right exists in a vacuum, especially the right not to be offended. A free society comprised of myriad rights means that rights will, from time to time, clash. When that happens, the question is how to best balance these rights and settle conflicts. That necessarily involves making judgments about which right is more fundamental to a free society.

The right to express one’s views – which includes not wearing a pride jersey – is one of those core values because so much else flows from free expression. Challenging the status quo with open, even robust debate, has been critical to securing lasting social change. From cementing women’s rights, securing gay rights, combating apartheid, and, more recently, recognising trans rights, debate has been, and remains, critical. That’s why protecting the right to freedom of thought, and belief, is more important than giving precedence to the views and feelings of another group, even when that group is society’s newest oppressed minority. That way lies a society that polices thought.

When inclusion is used as a commandment to tell people in a modern liberal democracy what to think, it ceases to promote respect for others. For example, a Medicare form that expunged the word “mother” and inserted the words “birthing parent” divides society.

It is high time that sham forms of diversity and inclusion adopted by sporting codes, embedded into corporate Australia and most other organisations, were dumped. Instead, fostering respect enables society, and organisations within it, a rugby team included, to recognise difference without expecting people to celebrate it or agree with each other.

This won’t suit the virtue-signalling zealots who are intent on forcing people to agree with their chosen moral code. But then again, zealotry, wherever it is found, is often the enemy of the common good.

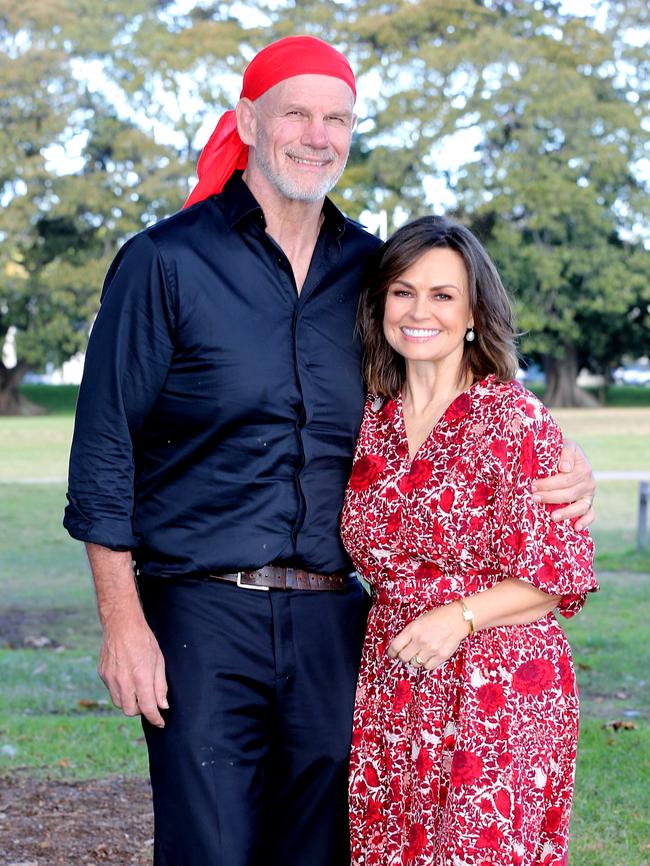

Is there a roster on the fridge in the Peter FitzSimons/Lisa Wilkinson kitchen where the pirate and the princess decide whose week it is to show the world how dimwitted and divisive woke politics has become? This week, after seven players from the Manly rugby league club decided to sit out Thursday’s match rather than wear a pride jersey that clashes with their Christian beliefs, FitzSimons wanted to know: “What the hell is wrong with you blokes that you don’t get it? You are prepared to trash the entire Manly season on this issue alone? … For what? … Can we have a statement from the seven of you, to make clear your views, so we can all understand?”