For Australia’s women and girls, this is our time of reckoning

The anger Australian women feel today goes far beyond feminism and even equality; it’s about making men change, or else.

Last year, the world’s first prime ministerial adviser on women’s affairs, Australia’s Elizabeth Reid, revealed she had suffered an uncomfortable sexual advance in the early 1970s from then governor-general Sir John Kerr.

Reid did not call it sexual assault. Rather she told an ABC podcast of an occasion when Kerr had started “pawing” her.

It was almost certainly the first time that Reid, now 78, had spoken publicly of an incident when she was in her early 30s and working for then prime minister Gough Whitlam, and when Kerr was almost twice her age.

Her job also involved working closely with Kerr, who was single after the death of his first wife and known to be seeking another.

He had previously embarrassed Reid by making a casual marriage proposal, but on this occasion, she says, “this man was trying to, I don’t know if I even have the words for it, trying to make out, or some phrase like that. Trying to get closer to me. I mean he was pawing me … with his hands and his body and I had to get out. I had to disentangle myself from it.”

Talking to reporter Alex Mann in the podcast, The Eleventh, about the 1975 dismissal of the Whitlam government, Reid sounds grave and appears to be processing the incident for the first time in a long time. It’s almost an accidental revelation. She does not call it sexual assault and indeed that term was not used back then when most behaviour short of rape was seen as something women just had to “disentangle” themselves from as best they could, whether in the office or the pub.

But an allegation of sexual assault it is in today’s terms — even if groping is acknowledged as a very long way from rape.

It’s extraordinary to think of the reaction if the woman charged with securing a more equal world for women had revealed Kerr’s behaviour at the time.

Then again, even if Reid had wanted to complain, there was no legal apparatus available for her to do so. There was no Sex Discrimination Act and sexual harassment was not yet “a thing”.

Kerr’s actions are ancient history, yet her story in this week when 100,000 women joined to declare “enough is enough” says much about the shifts around male power and women’s rights in the past half century.

If there was a period 10 or 15 years ago when younger women figured all the battles had been won and feminism was outdated, even embarrassing, the events this year suggest otherwise.

It is five weeks since Brittany Higgins threw a bomb into parliament; and three since the friends of Christian Porter’s alleged victim fired their shots. Those events will long be remembered as setting off the anger that has created a very tricky moment for our political leaders on both sides.

But the push for change is no longer just about justice in the Higgins and Porter cases — and thus is all the more difficult for politicians to shrug off.

Spin will not cut it.

At first, the demands seemed unclear. Were Monday’s marches about solidarity? About Canberra legislating for culture? Did the protesters want women to be able to walk anywhere without calculating risk? Were they conflating Brittany’s alleged rape with their own failure to win a promotion at work? Were they protesting about coercive husbands and patronising bosses? Did the zealots have the floor, demanding women’s testimony must always be believed?

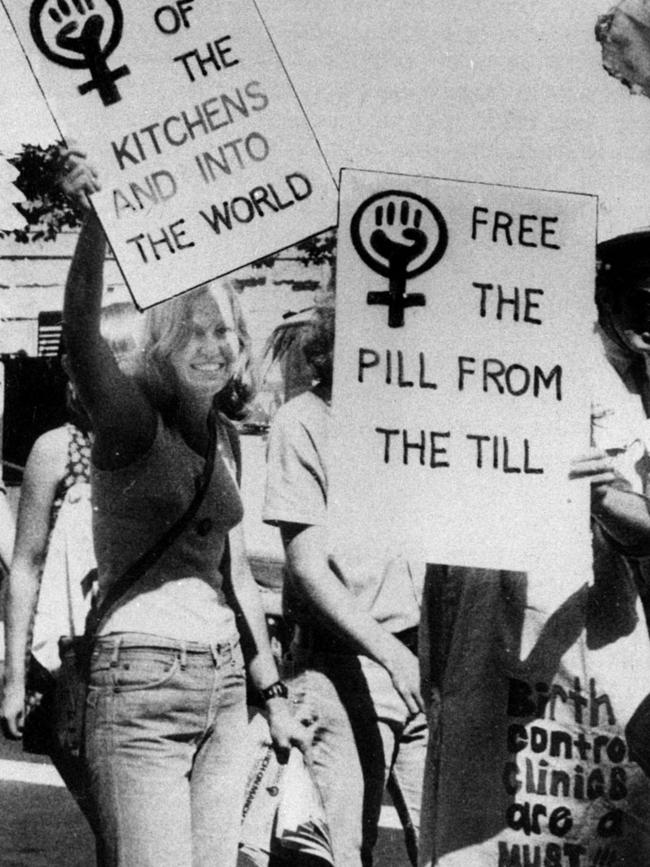

For many, the marches across the country recalled the women’s liberation movement of the 1970s, when activists were intent on busting systems that saw women as second-class citizens. For radical feminists back then, rape was a tool the patriarchy used to embed male power, a philosophy that sat behind more immediate demands such as the right for women to open a bank account without permission from a man; the right for victims of domestic violence to access safe houses; about access to contraception and abortion.

The present movement brings rape centre stage in a national conversation that has been unrestrained and insistent.

It has already ventilated views about power and consent likely to have a significant impact on sexual relationships, and indeed all relationships between the sexes.

It’s been both thrilling and confronting. The right for women to freely engage in sex on their terms to know that even when drunk or unconscious they will not be raped, to be protected by our legal system, has never been so clearly articulated on such a national platform for so long.

But it has been confronting to many because it has triggered memories of incidents long buried, and to others still grappling with the refusal of young women to be the traditional “gatekeepers” for male behaviour around alcohol and dress.

By week’s end, the conversation appeared to crystallise around two issues: how to achieve a higher level of convictions flowing from rape allegations; and how to shift male attitudes towards women to prevent sexual assaults in the first place.

This battle for “bodily autonomy”, as Sydney University’s Penny Russell calls it, is not new. Controlling women’s bodies has always been one of the ways in which equality has been “continually contested and undermined”, says the Bicentennial professor of Australian history.

“That was true in the 1880s and 1890s when (suffragettes) were seen as the shrieking sisterhood and ridiculed for even thinking about being in politics. The use of women’s bodies to police their conduct in public and to police their access to power has been very constant, and it has always been in different ways a focus for feminists.”

The difference between the 1970s and now is that back then feminists asked “why men did it, what was the power agenda that lay behind it? What is the political power of men that rape is working to support?” Today, says Russell, it’s about accountability: “It’s not why do men do this; it’s how do men keep getting away with this?”

Sexual assault is not the last of the big issues for women, says gender equity consultant Catharine Lumby, but it is one of the last big issues.

“We don’t have complete equality at work but we are getting closer to it,” she says. “Women do have more rights in Australia than they did, so that allowed this to become a focus.

“There is no question that there is a reckoning going on and there is a quite wide coalition of women who are saying enough is enough and we want change.”

Lumby, who is a professor at Sydney University, worries about trial by social media but says it has been the game changer here: “In the past when it came to harassment and assault, women have told their stories in single file, to friends and family, to counsellors, sometimes to the police and to the court”.

Now social media allows a collective voice that is rapidly shared and amplified. It has shattered the silence and it’s clear the support for women like Higgins and Australian of the Year Grace Tame and Porter’s accuser reflects a deep anger and frustration around what Russell terms “the cultures of silence and the protective cones that always close in around any men who are accused, and the innate distrust of the accusers”.

If feminism has found new force, Macquarie University professor of modern history Michelle Arrow says it has been building for a while. “When Beyonce stood at the Grammy Awards (in 2014) with the word feminist blazing behind her, I think a lot of young girls and women thought, ‘yeah, that’s kind of cool and OK’, she says. “I don’t think (feminism) carries the sort of stigma that it did 15 to 20 years ago when it felt old hat and people were saying that older ladies would not shut up.”

The #MeToo movement, of course, changed the rules around the capacity of women to call out criminal behaviour. But it’s been harder to call out risky behaviour, including dress codes and alcohol. Women and men alike strongly police the language around these issues — both in public and privately — and there is little space for a conversation about women’s responsibility to avoid potentially risky situations.

It’s absolutely justified, given centuries of victim blaming of women who “asked for it”. But parents who stress appropriate dress or controlled alcohol intake have little support at a public and cultural level. Instead, as Defence Chief Angus Campbell discovered recently, those who attempt to raise them, however well-intentioned, are likely to be censured.

Says Lumby: “We should be careful to separate the message about alcohol and responsibility for sexual assault. Whatever a woman is wearing, however much she has had to drink, if she is walking down a dark street (sexual assault is a crime).”

She has some sympathy for the argument that we need to distinguish between blaming women for sexual assault and noting what constitutes risky behaviour. But, she says, at the end of the day, responsibility for the crime rests with the perpetrator.

Language is incredibly important, not just around the language of consent. Arrow, whose award-winning book, The Seventies: The Personal, the Political and the Making of Modern Australia, was published last year, says the women’s movement changed the language around rape.

“In the 1970s, you were still hearing stories of men being driven mad by desire,” she says. “Rape was seen as a crime of sexual desire rather than a crime of power.”

The Reclaim the Night marches, she says, recognised that equality would never be achieved while women were afraid to go out on the streets at night.

Power balances are ultimately at the heart of every gender question, and Russell welcomes the attention to “the pockets, the places where these attitudes are still allowed to flourish, and indeed are cultivated and condoned”.

One of those places is boys’ private schools. “There is something about how boys are being brought up in 2021 to somehow regard girls as rightful property and fair game and to regard rampant sexual assault as something to be joked about and then denied,” she says.

She believes single-sex boys’ schools “woo parents with the idea that they will give their children access to privilege and power. That promise is bound up with some very old-fashioned notions of how you get power, how you use power, and who is entitled to it.”

Lumby says: “At the heart of the decision to sexually assault someone is a sense of entitlement.

“We still live in a highly gendered society and … in schools in Sydney’s eastern suburbs there are a lot of single-sex schools and a cohort of boys who engage in toxic male-bonding behaviour.”

Pursuing this argument around male power has always been tricky, and Lumby is keen to always cite the role of good men who support women’s rights. But when Tame told women at the Hobart march “men are not the enemy” she drew a relatively lukewarm response. Even the poster girl for fighting sexual abuse may find it difficult to prosecute that one.

Yet the “toxic masculinity” argument invites a “toxic femininity” response from some men, for example when they see placards like: “I’m 12 and sick of this shit.” It’s impossible to predict how this debate will play out for the next generation of men.

The passion around women’s rights shows little sign of abating. And Lumby thinks that it could “ultimately swing the next election — it’s that big”.

She says: “I have yet to see clear signs the PM and most of his cabinet get it. I think this has probably blindsided the PM and many in his cabinet. I have worked in the press gallery and I suggest there would be quite a lot of men — former politicians and staffers and maybe even a couple of male journalists — sitting around thinking ‘Holy hell, it’s coming home to roost’.”

Arrow agrees we could be at a moment of political opportunity for women.

“The Whitlam government recognised that something was happening in the 70s and tried to use some of that feminist anger to power its own election victory,” she says.

“If the activists are smart enough to keep this on the agenda, there will be an opportunity for women to be recognised as a bigger political constituency.”