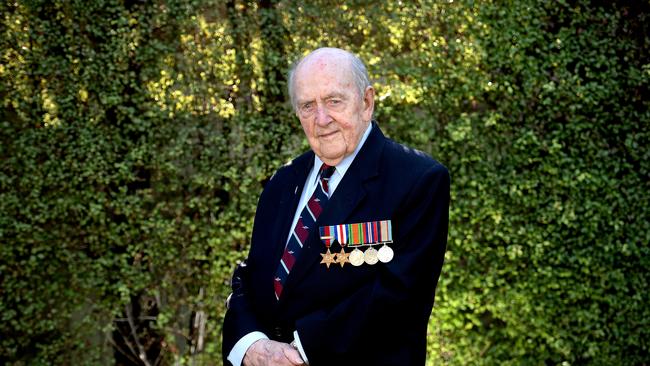

Flying ace Laurie Lamer wrote to Germans apologising for his raids

The humble boy from Moonee Ponds volunteered to fly perilous missions over Germany, but the deaths of innocents always troubled him.

If it hadn’t been Barry Humphries’ Dame Edna who put Moonee Ponds on the map, the suburb would have claimed Laurie Larmer. Larmer was hardly unique in willingly serving in Australia’s defence forces during World War II – a million did, half of them overseas of whom about one in nine never returned.

But after he had travelled through much more of life, and the youthful excitement and euphoria of his early years were timeworn – tempered like us all by experience, regret and loss – he chose to do something so powerful and humbling that it brought to tears the sons and daughters of the people he had once been sent to kill.

Larmer was born in Moonee Ponds 11 years before Humphries entered the world (in Camberwell) and with his family moved in 1935 to Ballarat, where his father ran a pub. He had a sense of adventure and when war broke out he sought to defend his country. But he didn’t want to be a soldier or a mariner – he thought this new thing of flying might be a thrill.

It would be. He was only 19 and had never driven a car.

In Australia he trained on small aircraft before moving to Canada, where he controlled larger aircraft before travelling to England, where he would ultimately be taught to fly Halifax bombers. The Halifax aeroplanes were cumbersome, vulnerable and had fatal flaws, but they led the campaigns that forced the Nazis to surrender. The Halifax was designed after its maker was asked after World War I to build “a bloody paralyser of an aeroplane”.

It looked ungainly but could travel at speeds up to 454km/h, reaching a height of 7300m and carrying almost 6000kg of bombs. It had a range of 3000km – or about the distance from Adelaide to Sydney and back.

Larmer wrote every week to his family in Ballarat but chose not to tell them all the details of his raids over Germany. But he recorded them – for instance: “March 12, 1945, Pilot (self) Operation Dortmund.” His sister Valda spoke this week about her brave brother. She is 94, and was about to head off to her body corporate meeting. She recalled her brother, who was studying commerce, coming home to say he was joining the air force. Soon he was headed overseas: “It was a big adventure for him.” In England he flew with the 51 Bomber Squadron, the only Australians to do so. It was dangerous work. There were a total of 125,000 in Bomber Command, 55,573 of whom were killed during raids. On one raid over Nuremberg in March 1944 almost the entire squadron was lost, including eight Halifaxes.

And the raids took a dreadful toll on Germany, unavoidably including innocent men, women and children. During a daylight attack on the Bavarian town of Bayreuth – home to the annual Wagner festival – on April 11, 1944, a third of the public buildings and industry was destroyed along with 4500 houses in which 741 people died.

The civilian deaths never sat well with Larmer. He told an ABC interviewer in 2015: “Knowing I’d bombed German cities, I had been responsible for the deaths of a lot of men, women and children … golly, what will I do?”

He decided to write to the mayors of the towns he had bombed to say how sorry he was. His notes read in part: “I write to you today to tell you that on (he included the date) I was with a force that bombed your city. I cannot recall the military reason for the raid and I make no apologies for it. But I deeply and truly regret that we were responsible for the deaths of so many innocents.”

Among the many replies was one from the mayor of Boizenburg, about 50km inland from Hamburg: “Many thanks for your letter … I was very surprised to receive it. Boizenburg and every German has to be happy that Allied forces defeated Hitler-Germany and freed the world from the horrible dictator. You did right in bombing the German cities and it is not your guilt that civilians died during your attacks. I have to thank you for your fight, and I am very sad that the world has not really learned from the cruel time from World War 2.”

After the war, Larmer worked in the automotive industry and ran pubs. In 2015 he was one of 116 Australians awarded a Legion of Honour, France’s highest military decoration. He received an OAM for services to the community in the Queen’s Birthday honours list. The German consulate sent flowers to his funeral.

Laurie Larmer Airman. Born Moonee Ponds, Melbourne, September 15, 1923; died Strathmore, Melbourne, April 14, aged 99.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout