Flesh-eater on the move

Scientists know little about the flesh-eating bacteria M. ulcerans — except it is spreading.

If May Smith thought she had left Daintree ulcer behind when she retired to the high country of far north Queensland, she was sadly mistaken. The 85-year-old wrote the book on this horrifying tropical disease when she was director of nursing at Mossman Hospital, but here it was, red raw and confounding, on her doorstep in range-top Julatten.

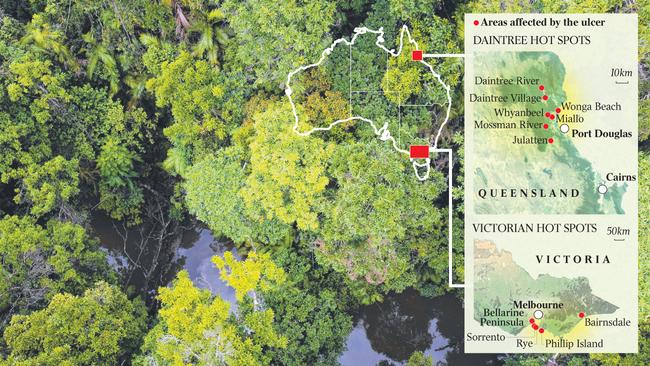

The story of how it got there takes some explaining, but so does Daintree ulcer. You might have heard of its Victorian sibling, Bairnsdale ulcer. Somehow, the focal point shifted from east Gippsland to Phillip Island, across the bay to the Bellarine Peninsula and then back again to Mornington Peninsula, where it poses a serious public health threat. So far this year 213 cases of Bairnsdale ulcer have been confirmed.

The culprit, Mycobacterium ulcerans, is a real piece of work. Closely related to the pathogens that cause tuberculosis and leprosy, it is a voracious flesh-eating bacterium that attacks living tissue, unleashing infections that can poison an entire limb while suppressing any fightback by the body’s immune system. In many cases, surgery is the only option.

The good news is that cases of M. ulcerans — to use the medical shorthand — are relatively scarce, a function of their reductive evolution. Outbreaks have been confined to the lowlands of equatorial Africa, where the disease is called Buruli ulcer, Papua New Guinea and the two locales bookending Australia’s eastern seaboard. But that’s of limited consolation to victims facing two months of intensive treatment with antibiotics usually reserved for TB, and the knife if the drugs don’t do the trick.

“As soon as I had the ulcer removed it was amazing after feeling unwell for quite some time. It was this rumbling infection that was … putting a strain on everything,” says 47-year-old Karri Pearson, pointing to the 6cm scar from an operation she had in July on her infected right arm.

The mystery of Daintree-Bairnsdale ulcer has occupied some of the best scientific minds in the country for nearly 30 years and it only keeps deepening. To start with, what on earth is a tropical disease that seemingly took root in a steamy patch of rainforest 90 minutes’ drive north of Cairns doing in distant Victoria? And why is it on the march in the chilly south, flaming out in one hot spot to re-emerge in another, leapfrogging all the way to the approaches of Melbourne?

One of the few constants has been the narrow distribution of the disease in far north Queensland, where ground zero was essentially static, sandwiched between the mouths of the Daintree and Mossman rivers and the thickly forested mountains rolling up to the Atherton Tablelands.

But as we report in the news section, even this is in flux with the appearance of three cases in Julatten, fully 450m above sea level.

Smith, who saw just about all there was to see of Daintree ulcer when she was nursing and wrote it up for a masters of science thesis in 1996, says she was unpleasantly surprised to learn it had spread to her retirement haven on the tableland: “I would love to know why but I don’t think anyone can be positive about anything with this disease,” she says.

“There are too many ifs and buts. If there is anything I have learned over the years it is we have barely scratched the surface in terms of coming up with answers.”

Yet bit by bit scientists are piecing together an intriguing picture of M. ulcerans and the exotic toxin it produces.

This is lipid-based, unlike the venomous output of other notorious bacterial pathogens such as cholera, which comprise bigger and more complex proteins.

What does this mean for a human patient? Well, the antibiotic properties often seen in lipid molecules are reversed in the case of M. ulcerans: as they multiply, the usual immune response by white cells is shut down by the toxin, accelerating the infection.

Typically, the ulcer starts as a harmless-looking spot which turns into a lump, breaks open, then grows into an angry-looking sore, framed by reddened flesh. If left untreated, the necrotic, custard-like sludge can reach down to the bone and poison that as well.

In its most severe oedematous form, the infection spreads beneath the skin of an arm or leg before erupting, inflaming the whole limb. Amputation is required in extreme cases — which is what nearly happened to chef Peter Ryan, 70, when he contracted Daintree ulcer in 1996. He remembers that Smith saw him at Mossman Hospital and immediately recognised he was in trouble.

The enduring, intertwined personal connections between patients, physicians and researchers are another feature of this curious corner of medical science.

Luckily, a last-gasp course of drug therapy worked and Ryan’s infected right arm was saved on the operating table, leaving a scar that runs from the elbow most of the way to his wrist.

In 2017, it was the turn of his 67-year-old business partner Richard Seivers, maitre d’ of their popular restaurant outside Daintree village. The ulcer on the left hip had to be cut out when he had an adverse reaction to the antibiotics.

“I’ve never felt worse in my life,” Seivers says quietly.

The relatively low number of cases in far north Queensland means the disease is very much the country cousin of Bairnsdale ulcer in terms of research and resources to combat it — even though the strains are virtually identical and equally potent.

In 2015, there was just one notification of Daintree ulcer. But the Julatten flare-up is not the only cause for concern.

In 2011, 64 people were infected in an outbreak centred on the township of Wonga Beach, a small community of brick-and-tile homes built on reclaimed sugar cane fields south of Daintree River.

By 2012, the incidence was down to 12 cases and continued to fall as the emergency ramped up in Victoria, peaking at 265 cases last year. Still, no one has yet got to the bottom of the Wonga Beach surge, on the back of a destructive summer wet in Queensland that unleashed lethal flooding in Brisbane and the Lockyer Valley, and a maximum-strength category 5 cyclone in the tropical north.

Moreover, the incidence of Daintree ulcer is showing signs of ticking up again, albeit modestly.

Of the five cases reported to date this year, three have come in the past five weeks, Queensland Health confirms. The rainy season was long and heavy — stretching from last December to May.

Locals still recall the clouds of mosquitoes, midges and sharp-stinging March flies that the 2011 wet brought out. If a transmission theory developed in Victoria holds, the insect population is central to how Daintree ulcer infects people. The equation seems straightforward enough: more rain equals more contagious vectors carrying the bug equals more cases. That still doesn’t account for why the disease travelled upward to Julatten but not sideways to, say, Port Douglas.

From her veranda at night, Smith can see the glow of lights from the thriving resort centre on the coast, less than 10km away as the mozzie buzzes.

Yet in all these years, not a single case of Daintree ulcer has been shown to have come from the town. Go figure, Smith says: “Mosquitoes can fly or be carried on the wind for miles and miles. If it was just the insects carrying the bacteria hundreds would have it in Port Douglas and we’d all have it here. We don’t. And none of the theories account for that.”

What scientists do know through genetic backtracking is that M. ulcerans originated not in the jungles of Africa, as might be expected, and where it affects thousands, but in PNG. The germs that cause Daintree ulcer, while a tight DNA match to the Bairnsdale strain, are the spitting image of the Papuan progenitor.

From there, the bacteria spread to Africa in two waves — the first about a 1000 years ago, the second at the turn of the 19th century, roughly 100 years after it arrived in Victoria in the early 1800s.

“Our preconceptions are that this is another HIV-like out of the forests of Africa story,” says Tim Stinear, a professor of microbiology at the University of Melbourne’s Doherty Institute. “But, no, that’s not what it actually is.”

Stinear has been working on the bug for more than two decades with colleague Paul Johnson, director of research at Austin Health, also in Melbourne, who has been involved in the hunt for answers even longer.

Both have collaborated with Smith through the years, sometimes staying with her while performing field work in the Daintree catchment. Another important figure, John McBride of James Cook University, a Cairns-based expert in tropical disease, has a holiday home in Julatten near hers.

Research teams led by Stinear and Johnson have established that the “reservoir” of the disease in Victoria is the native possum, both a carrier and victim of M. ulcerans.

Mosquitoes, the intermediate vector in the chain of transmission, bite an infected animal or pick up the germs by landing on an open sore or contaminated droppings. In hot spots such as the holiday towns of Rye and Sorrento on the Mornington Peninsula, up to 10 per cent of the possum population is thought to be infected.

People are next in line when bitten by a carrier mosquito — though it is not clear whether this is blood-to-blood transmission, as with malaria, or a consequence of the skin being broken, effectively inoculating the human host with M. ulcerans clinging to the body of the insect.

Johnson says the conundrum of how the disease has flared and died in one locality — such as Phillip Island, where he first encountered it 30 years ago — before cropping up in another hot spot, could be explained if the local possum populations eventually became immune.

“In broadbrush terms it sweeps through the possums … like a wave,” the professor of microbiology and immunology says. “They either get better or die. The humans are the inadvertent spillover hosts and when it clears itself out of the possum population people stop getting it as well.”

Take Phillip Island.

“We’ve not had a (human) case there for years,” Johnson adds.

But the Daintree is a much more puzzling proposition. Few possums live in the tropical rainforest and, despite years of searching, the nearest researchers have come to finding an animal host is from two positive samples in bandicoot droppings, possibly from the same animal near Daintree River, and two positive mosquito samples at Wonga Beach.

Smith is convinced the key to unlocking the mystery lies undiscovered in the knotted green depths of the primeval selva. Her late friend, Bob Lanskey, a long-serving GP in Mossman, thought leaf mould was the reservoir: March flies breed in it after heavy rain and the forest litter is used as garden mulch across the district. Smith hypothesises the bacteria also could live in the soil.

Stinear agrees she might be on to something because the more Australian scientists learn about M. ulcerans, the more they realise how little they know for sure about this baffling disease.

“I think May is right,” he tells Inquirer.

“We can’t draw a direct connection about what’s happening here in the southeast and what’s happening in far north Queensland. It’s an open question.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout