Family law reform cancels dads’ right to share parenting

The government has introduced a sweeping number of amendments to John Howard’s 2006 reforms that will restore maternal preference in custody disputes.

However, before a Senate inquiry could be held, opposition senator Paul Scarr complained there was only about a week to prepare any response and only one day of hearings before producing a report on the bill.

Why the rush? There is one overriding reason. It is because the proposed reforms are not really reforms. This bill is an attempt to wind back the clock in family law using domestic violence as leverage to negate the concept of shared parenting, the pillar on which reforms brought in under the Howard government in 2006 rested.

The presumption of equal shared parenting has never been popular with feminist groups. The ink on the paper of the 2006 reforms was barely dry before feminists were preparing to counter them, and the most effective counter-attack is the spectre of domestic violence.

Children should never be placed in violent circumstances ridden with pathologies, whether from mother or father, but in general it would seem a true feminist proposition that children’s lives should be influenced equally by mother and father.

However, the principle of equal shared parenting responsibility enshrined in the Howard reforms did not always mean a presumption of equal shared time. This is not always practical and it was an element of confusion in the 2006 reforms that was deliberately inflated by antagonistic feminists.

Both parents are entitled to be involved with their children, but focusing on the issue of equal time has allowed the government and the ALRC to go much further in cancelling the 2006 reforms and turned the debate away from the benefits of a strong affectionate relationship with both parents.

Under the pretext of “clarifying confusion”, the government has introduced a sweeping number of amendments and deletions to the 2006 reforms that effectively will restore maternal preference in custody disputes.

Concerns have been raised by family law practitioner groups about the policy intention underlying the deletion of many sections of the Family Law Act inserted in 2006, since those reforms assuming equality of decision-making by both parents had bipartisan support. They were amended in only minor ways by a Labor government in 2011 to enhance the focus on family violence and, according to research by the Australian Institute of Family Studies, the Howard reforms were “overwhelmingly supported by parents, legal professionals and family relationship service professionals”.

According to Patrick Parkinson, Australia’s leading professor of family law, “What seems apparent enough from the text is that it reverses, in a wholesale way, almost all the changes that were made to the (Family Law Act) … Those amendments were made after one of the biggest public inquiries in recent history.”

Despite the reservations of family law practitioner groups in Queensland, Western Australia and NSW, Law Council of Australia president Luke Murphy, in a presentation at an event last month attended by Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus, welcomed the bill, particularly the proposed repeal of the presumption of equal shared parental responsibility. He claimed in his address “parties are agreeing to potentially unsafe parenting arrangements in the shadow of a misunderstood law”. Who says? Again there is a broad assumption of potential violence, despite agreement of both parties.

The overwhelming emphasis in the amended legislation on domestic violence is puzzling since violence affects only a small proportion of separated families and overall incidence is declining.

Although the figure of 22 per cent experiencing undefined sexual violence has grabbed headlines, according to Australian Bureau of Statistics personal safety surveys the true rates of intimate partner violence against women have dropped from 2.3 per cent in 2016 to 1.5 per cent in 2021-22.

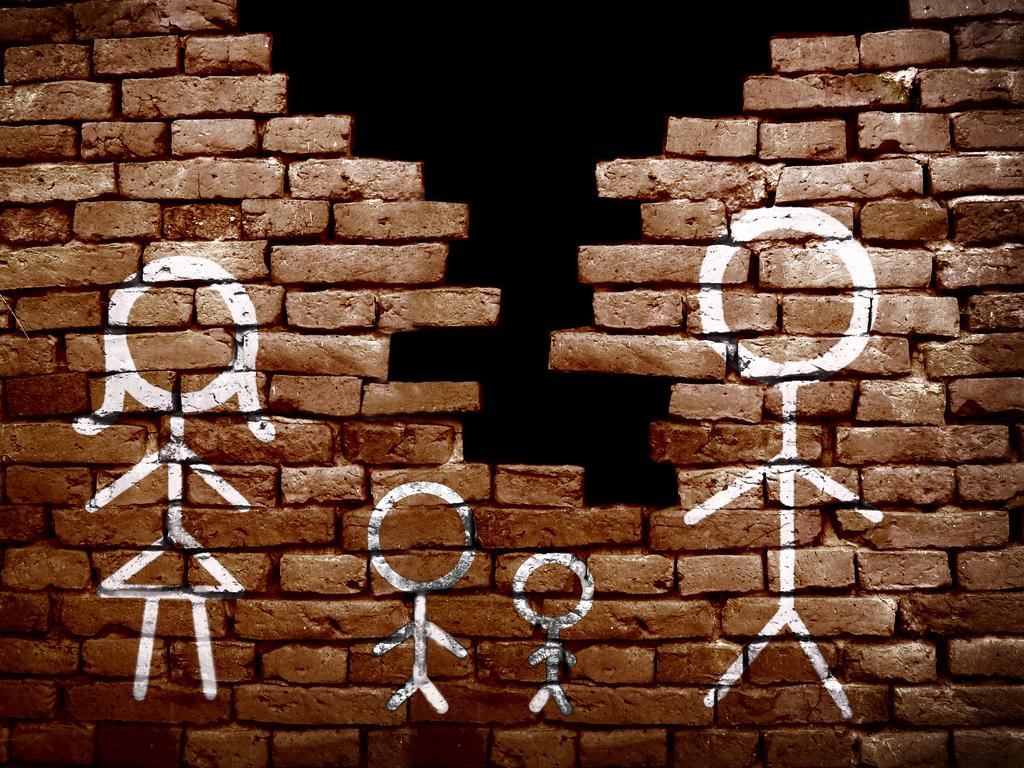

The underlying presumption that equal shared parental responsibility is good for children has been replaced with a presumption of possible family violence, and that this will come from the father. This bill rewrites “the best interests of the child” from the Howard bill that rightly promoted children’s need for both parents in their lives and even removes the word meaningful in describing the child’s relationship to both parents.

As Murphy says, should the bill pass it will be essential for the legal profession and the broader community to be educated on what these changes will mean in practice. But the upshot is that feminists have achieved their aim of capturing family law. By doing so they have ignored all the research that says fathers are a necessity in their children’s lives. It will mean a return to the old model of mothers being given custody of children, with fathers squeezed out of the picture and a possible concomitant rise of false allegations of violence.

According to a YouGov survey this year published by the Domestic Abuse and Violence International Alliance, 15 per cent of Australian males have been subject to false allegations of abuse. But on the ground right now many don’t know about the law changes. There will be many fathers expecting an equal say in their children’s lives – but they won’t get it.

Distraction is a useful tool in politics. The government has used the voice referendum to distract from a bill coming up in the Senate the week after the vote. The Family Law Amendment Bill 2023 proposes amendments to the Family Law Act primarily in response to recommendations by the Australian Law Reform Commission in relation to parenting and children.