Evolution of climate fear

A report warning that biodiversity was on the road to ruin has echoes of dire predictions 50 years earlier.

In the lead-up to the latest report warning of a cataclysmic future for the natural world there was a frenzy behind the scenes to make sure it got the world’s attention.

Environment groups were briefed to spread the message that a UN report would be a supercharged affair when it was released this month.

The headline figure would be that one million species faced extinction. Biodiversity on planet Earth was on the road to ruin.

“Protecting biodiversity means protecting mankind because we human beings depend fundamentally on the diversity of the living,” UNESCO director-general Audrey Azoulay said in announcing the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services report in Paris earlier this month.

For many the report had echoes of the dramatic projections made almost a half-century ago when Paul Ehrlich predicted a “great die-off” in which billions would perish.

In 1970, S. Dillon Ripley, the secretary of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, and an ornithologist and wildlife conservationist, had assessed that before the turn of the 21st century between 75 per cent and 80 per cent of all the species of living animals would be extinct.

There have been questions about exactly how the latest million species extinction figure was arrived at, particularly given that it includes species that will probably never be identified or recorded.

The full global assessment report is yet to be published but the extinction rate appears to have been generated by extrapolating existing threatened species lists into the unknown.

New climate

The real import of the global assessment, however, is the attempt to set biodiversity on to an equal footing in the world politic with climate change.

The next step will be an important meeting scheduled for China next year at which the IPBES is planning to emerge as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change equivalent for nature.

IPBES chairman Sir Robert Watson did not disappoint in setting the tenor of alarm. The overwhelming evidence of the global assessment presented an ominous picture, he said.

The health of ecosystems on which humans and all other species depended was deteriorating more rapidly than ever. Humans were eroding the foundations of their economies, livelihoods, food security, health and quality of life worldwide. But it was not too late.

“Through ‘transformative change’, nature can still be conserved, restored and used sustainably — this is also key to meeting most other global goals,” Watson said.

“By transformative change, we mean a fundamental, system-wide reorganisation across technological, economic and social factors, including paradigms, goals and values.”

The punchline mirrors exactly that of the IPCC’s report into the impact of 1.5C warming released late last year to encourage governments to increase their action on climate change.

That report concluded “rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society were needed”.

The message is being eagerly embraced by a new generation of activists increasingly persuaded by a resurgent consequentialist notion that, on climate and nature, the ends can justify the means.

Doubtless the natural world has problems. But there is a long history of dire predictions that simply have not come to pass.

At the core is robust debate on whether rising prosperity is a force for environmental good rather than ruin.

Innovative evidence

The stark case is made out in the global assessment that was billed as the first intergovernmental report of its kind that includes “innovative ways of evaluating evidence”.

Compiled by 145 expert authors from 50 countries during the past three years, with inputs from another 310 contributing authors, the report assesses changes across the past five decades to provide “a comprehensive picture of the relationship between economic development pathways and their impacts on nature”.

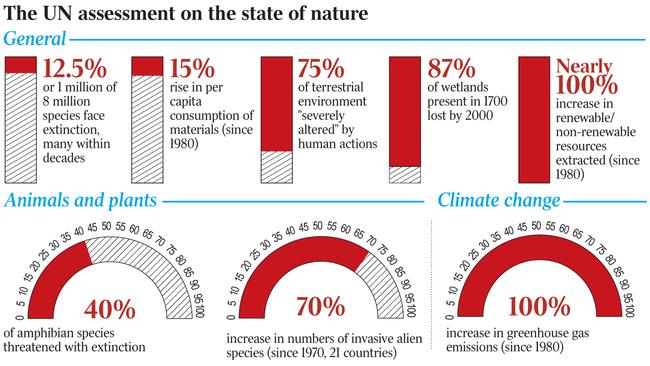

The report finds that about one million animal and plant species are threatened with extinction, many within decades, more than ever in human history.

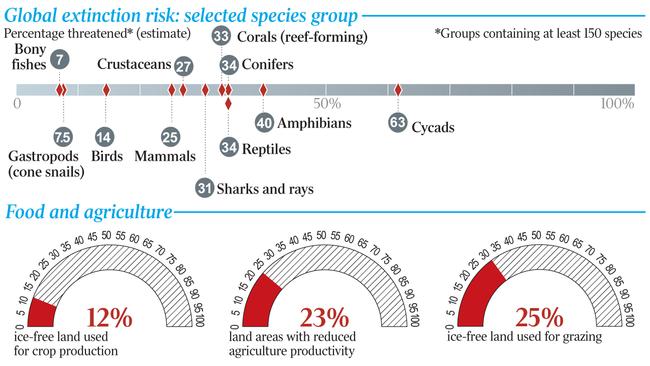

The average abundance of native species in most major land-based habitats has fallen by at least 20 per cent, mostly since 1900. More than 40 per cent of amphibian species, almost one-third of reef-forming corals and more than one-third of all marine mammals are threatened. The picture is less clear for insect species, but available evidence supports a tentative estimate of 10 per cent being threatened.

The main culprits are, in descending order: changes in land and sea use; direct exploitation of organisms; climate change; pollution and invasive alien species.

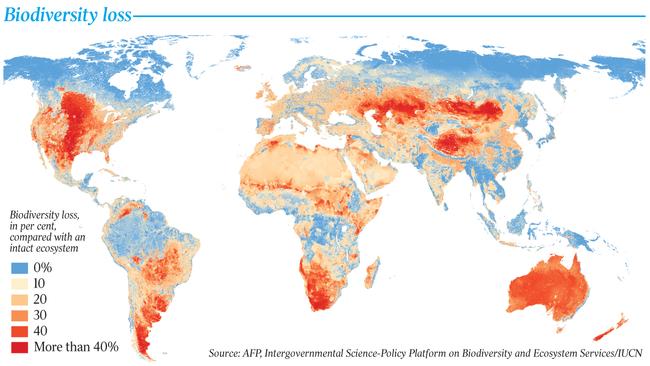

Three-quarters of the land-based environment and about 66 per cent of the marine environment have been significantly altered by human actions.

More than one-third of the world’s land surface and nearly 75 per cent of freshwater resources are now devoted to crop or livestock production.

The value of agricultural crop production has increased by about 300 per cent since 1970, raw timber harvest has risen by 45 per cent and 60 billion tonnes of renewable and non-renewable resources are extracted globally every year.

Urban areas have more than doubled since 1992.

Plastic pollution has increased tenfold since 1980.

Wealth aids diversity

The report warns that negative trends in nature will continue to 2050 and beyond in all of the policy scenarios, except those that include transformative change.

Report co-chairman Eduardo S. Brondizio, a professor of anthropology at Indiana University, says to better understand the main causes of damage to biodiversity it is necessary to understand the history of global interconnection of complex demographic and economic indirect drivers of change.

“Key indirect drivers include increased population and per capita consumption; technological innovation, which in some cases has lowered and in other cases increased the damage to nature; and, critically, issues of governance and accountability,” he says.

“A pattern that emerges is one of global interconnectivity with resource extraction and production often occurring in one part of the world to satisfy the needs of distant consumers in other regions.”

This is one of the reasons that debate about whether prosperity results in better or worse environmental outcomes remains vexed.

British author Matt Ridley argues what really diminishes biodiversity is a large, poor population trying to live off the land.

“As countries get richer and join the market economy they generally reverse deforestation, slow species loss and reverse some species declines,” he says.

Ridley says the threat to biodiversity is “not new, not necessarily accelerating, mostly not caused by economic growth or prosperity, nor by climate change, and won’t be reversed by retreating into organic self-sufficiency”.

He says much of the human destruction of biodiversity happened a long time ago and that species extinction rates of mammals and birds peaked in the 19th century (mostly because of ships taking rats to islands).

For Australia, of the 24 bird species made extinct during the past 200 years only one has been on the mainland, the others on islands. Seven frog species and 27 mammal species or subspecies are strongly believed to have become extinct in Australia since European settlement.

“We’ve been here before,” says Ridley.

“In 1981, the ecologist Paul Ehrlich predicted that 50 per cent of all species would be extinct by 2005. In fact, about 1.4 per cent of bird and mammal species, which are both easier to document than smaller creatures and more vulnerable to extinction, have gone extinct so far in several centuries.”

“Why are wolves increasing all around the world, lions decreasing and tigers now holding steady?

“Basically because wolves are in rich countries, lions in poor countries and tigers in middle-income countries. Prosperity is the solution, not the problem.”

Wilderness Society national director Lyndon Schneiders says as prosperity increases, the impact of growth is often sent offshore. “As things recover in the developed world, the biodiversity loss often is getting worse in developing nations,” he says.

“The West has been moving its destructive practices to the developing world.”

If the argument is that greater prosperity will drive better outcomes as countries develop, the question is: where do the resources come from to support that transition?

Australia’s role

For eco-modernists the answer lies in technology and improving efficiencies in production of food and energy to lessen the impact on nature. Schneiders supports a view put by Ridley that urbanisation can be a positive for the environment but says Australia is split because of its low population and commodity export focus.

Economically Australia mirrors the developed world but environmentally it shares a lot in common with developing nations, including high levels of land clearing. For Schneiders the challenge is not to transform capitalism but to improve planning and regulation.

The competition to date has been between a regulatory approach and the orthodoxy of market mechanisms.

Schneiders argues this has produced the worst of all worlds — lots of green tape with no one to regulate it. “There has to be a model that works for both exporters and environmental protection,” Schneiders says.

For environmental groups the marriage of biodiversity objectives with climate-change policy presents a pathway forward.

“If carbon pricing creates a driver to reduce emissions and build carbon sinks the challenge is to marry that with conservation and biodiversity objectives,” Schneiders says.

The Coalition’s direct action approach is one way but it is hampered by the fact it relies on limited government funding.

Globally, Australia is being encouraged to take a leading role in the talks in China, which are aiming to set a target of protecting half the planet by 2050 with an interim target of 30 per cent by 2030.

Australian Conservation Foundation nature program manager Basha Stasak says the federal government must strongly argue for a global deal that has clear measurable targets that halt the extinctions, ensure species populations recover and protect critical ecosystems.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout