Election 2022: Can Labor keep Australia safe?

There was a significant period when one side of politics was unfit for government on national security grounds.

Marles, though generally serious on security, has had a poor election campaign and has a history of making occasional remarkably silly statements about China. Nonetheless, he will get the defence ministry if Labor wins.

Defence Minister Peter Dutton accused Labor’s foreign affairs spokeswoman Penny Wong of claiming she can repair all the difficulties with China through honeyed words in Beijing. There is no evidence Wong thinks this. It is a baseless and fairly disgraceful claim. Morrison did not repeat it, but focused his criticisms on Marles’s statements.

Albanese and Wong, and Labor defence spokesman Brendan O’Connor, have been strenuous in blaming the troubled relationship between Canberra and Beijing on Xi Jinping’s highly aggressive leadership.

Chinese outlets have attacked both the Morrison government and the Albanese opposition while praising the Greens.

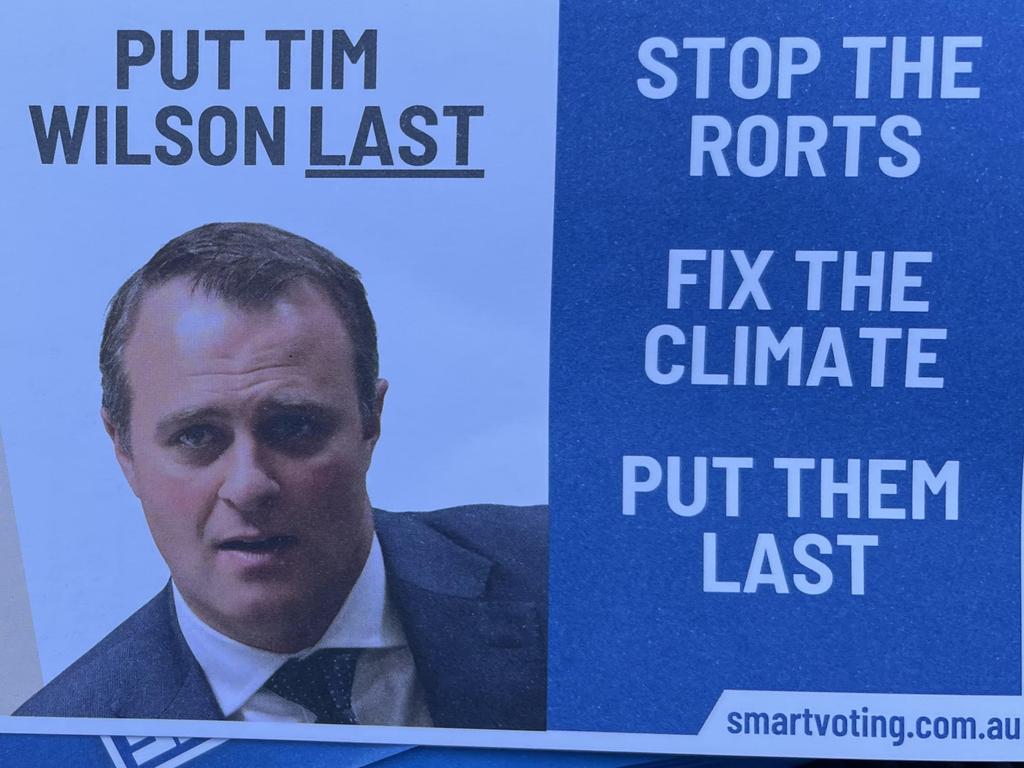

The only candidates with a chance of winning seats whose security views make them dangerous are the Greens and the so-called teal independents.

Monique Ryan, challenging Josh Frydenberg in Kooyong, could have been reciting Chinese embassy talking points when she blamed Canberra for problems in the China relationship.

There was, however, a significant historical period – a quarter of a century – when one side of politics was unfit for government on national security grounds. That is from 1951, when HV Evatt became Labor leader, until 1977, when Bill Hayden replaced Gough Whitlam.

The corollary is that for the past 45 years, both sides of Australian politics have been at least minimally fit for government. That doesn’t mean that they got policy right, nor been totally immune to foreign interference, especially in recent years from Beijing.

The main reason Labor spent all but three of those 26 years in opposition was the public understanding that it was infiltrated at many levels by communists, was compromised by the Soviet Union, and was unreliable on security.

There were always plenty of good Labor people fighting these influences. Labor’s problems were definitively fixed by Bob Hawke’s government. Hawke is one of the great figures in Australian national security history. He transformed Labor’s culture and ran his government as the polar opposite to the Whitlam government.

Before him, Hayden, too, repudiated much Whitlam madness. Nonetheless, Labor continues, all these decades later, to suffer lingering historical question marks arising from the Evatt and Whitlam delinquencies.

These are too little recounted today, partly because they are so unsympathetic to the cultural left which always casts conservatives as history’s villains. Today, the Chinese state is infinitely richer, and more nimble, than the Soviets were. The security challenges of Cold War 2.0 will be more daunting than those of the first Cold War. Its history should be common knowledge

National security has always been at the heart of Australian political life. The Australian colonies, covering an area as big as western Europe, federated into one nation in 1901 because of national security – the challenge of asserting sovereignty and control over Australian territory.

Our leaders have been better at national security than they generally get credit for. Typically, they have been independently minded, tying themselves to great powers in order to provide Australian security.

The most brilliant and perhaps most consequential, certainly the most eccentric, prime minister was Alfred Deakin. In 1908, Deakin, using the limited tools of a PM in the newly minted federation, defied the British Foreign and Colonial Office to invite Teddy Roosevelt to send his Great Fleet to Australia.

Deakin, already worried about the military power of Imperial Japan, used the overwhelming public sentiment occasioned by this visit to polarise the nation in support of building an Australian navy, again in opposition to British policy. He also foreshadowed the US alliance, eliciting from Roosevelt the first ever expression of US military commitment to Australian security.

Australian policy was poor in the 1930s, overly reliant on the false security of the British base in Singapore. Nonetheless, as Jeffrey Grey argues in his A Military History of Australia, the initial wartime leadership of Robert Menzies, PM when World War II broke out, was credible.

Menzies nonetheless lost the support of his colleagues and Labor leader John Curtin formed government. Curtin was an effective wartime leader. Like Hawke many decades later, he reformed Labor’s political culture to cope with reality. Labor policy had been that Australia’s military should not fight overseas and that Australian conscripts should in particular never be sent overseas.

Faced with the struggle for national survival, Curtin rightly turned all that on its head. He looked to America for security. With Hawke, Curtin is the foundational Labor figure on security.

Curtin’s successor, Ben Chifley, founded the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation after Soviet penetration of External Affairs in Canberra in World War II. Britain and America did not want to share intelligence with Canberra. Menzies became PM again in 1949 and was a towering figure in security. His foreign minister, Percy Spender, secured the ANZUS Treaty with Washington. Menzies also pioneered rapprochement with Japan.

Everything went wrong for Labor once Evatt took over. The three-volume official history of ASIO is nonpartisan, desperately keen not to make any political enemies for ASIO today and very undramatically written. It is, nonetheless, a truly shocking indictment of Evatt, and later Whitlam.

Evatt’s chief adviser on foreign affairs was John Burton whom he appointed, at age 32, as head of the External Affairs Department. The ASIO history comments: “Neither Evatt nor Burton had much respect for security.” It also tells of the need for public servants to ransack Evatt’s hotel rooms before hotel staff arrived because secret documents were invariably left lying around.

The legendary intelligence scholar, Desmond Ball, concluded that Burton himself was most likely a Soviet agent, though the official ASIO history does not make this claim. The ASIO history reports a senior British Foreign Office report, when Labor was still in government, concluding: “The Americans rate Australian security very low… based in part on actual experience of Australian insecurity during the war, and in part on their general distrust of Australian Labor politicians and their particular distrust of Evatt and Burton.”

Evatt’s most bizarre performance arose from the defection of the KGB officer Vladimir Petrov and his wife, Evdokia, in 1954. Petrov was one of the most important Soviet defectors of the Cold War. Several of Evatt’s staff were shown to have co-operated intimately with the Soviet embassy. But Evatt claimed in parliament, bizarrely, that the documents Petrov supplied were forgeries, cooked up by ASIO with Petrov’s assistance.

In surely the most crackpot speech ever delivered by an Australian major party leader, Evatt revealed to parliament that he had written to the Soviet foreign minister, Vyacheslav Molotov, who had replied assuring him there was no Soviet espionage in Australia and Petrov’s documents were all fake. This was the Molotov who had been instrumental in forming the Nazi/Soviet pact at the start of World War II.

Heaping insanity upon insanity, Evatt proposed an international commission, with Soviet co-operation, to investigate Petrov’s claims. In The Menzies Era, John Howard asks: “How could the alternative PM of Australia take the word of a senior member of the despotic Soviet regime in preference to those of respected judges and security professionals in his own country?”

The Petrov royal commission concluded that the Soviet Union had run a spy ring in Australia using members of the Communist Party, and had paid the Communist Party large sums of money, “Moscow gold”.

The Labor Party split and many anti-communists went to the Democratic Labor Party. The unions which were sympathetic to the DLP were welcomed back into the Labor Party under Bob Hawke in the 1980s.

Whitlam, while always far saner than Evatt, was almost as bad on national security. Whitlam started on Labor’s right but after being challenged by the far-left Jim Cairns drove ever further to the left to maintain his position in the party. Even the most tepidly written accounts of the Whitlam period, like the official history of ASIO, are utterly gobsmacking by today’s standards.

In a seminal piece in The Australian, former Labor NSW premier and later foreign minister Bob Carr courageously wrote that Labor was indeed for a time unfit for office on national security grounds. Cairns, for a time deputy prime minister under Whitlam, affectionately described the murderous communist dictators Josef Stalin and Mao Ze Dong as “leaders of world socialism”.

The left fell just one vote short at an ALP national conference from passing a motion demanding the expulsion of US communications facilities, which would have destroyed the US alliance.

Mark Aarons, whose family was at the heart of the Communist Party, in his important book, The Family File, describes the “dual ticket” system of some senior Labor figures holding a simultaneous clandestine membership of the Communist Party.

Carr concluded that much of the impetus for Labor’s far-left policies came from the Communist Party and its Labor allies.

Some of Whitlam’s specific actions were grotesque. He refused initially to allow any of his staff to undergo the normal security vetting. His attorney-general, Lionel Murphy, refused to allow ASIO to eavesdrop on or keep surveillance over east European diplomatic establishments in Australia.

Murphy used the commonwealth police to conduct a raid on ASIO headquarters, thinking ASIO had a big file on him and was in league with Yugoslav terrorists. This was madness on Murphy’s part. As the ASIO official history reports, the raid led to Washington suspending intelligence sharing with Australia.

Harvey Barnett, ASIO director under Hawke, reported in his memoirs that allies were “aghast and concerned” that a grab for security service records was often the first step in an undemocratic coup. Whitlam never trusted Murphy and some intelligence information was kept from Murphy by Whitlam, a wildly dysfunctional dynamic between PM and AG.

Whitlam’s security derelictions were numerous and bewildering. At the fall of Saigon at the end of the Vietnam War, he refused to let any but a tiny handful of South Vietnamese who had been closely associated with Australia come here. He personally vetoed a flight of Cambodian orphans. The whole performance was one of the cruellest and most self-indulgent decisions any PM has ever taken.

Whitlam in 1975 also commissioned Bill Hartley, who worked for Libya and Iraq and incongruously was also on the Labor Party’s national executive, to seek $500,000 in secret funding for the ALP from the Iraqi Ba’ath Socialist Party, which even then was dominated by Saddam Hussein.

Hawke in his memoirs wrote about this unparalleled act of infamy in Australian politics: “That Whitlam, who was aware of the abhorrent nature of this regime, should acquiesce appalled me beyond measure.” Whitlam suffered two great electoral landslide defeats in 1975 and 1977.

Hawke also wrote that the mere presence of Hartley and his ilk in the Labor Party gave him serious ethical reservations about whether he should even seek preselection in such a party. However, Hawke went on genuinely to transform and ennoble the Australian Labor Party.

With Kim Beazley, and others, he vanquished the extreme left on national security. He embraced and modernised the US alliance, transforming US communications bases into joint facilities. He socialised his party into the US alliance and into mainstream social democratic approaches to security and defence. He acted ruthlessly to expel Soviet KGB agents trying to recruit Labor figures. He is the only PM in my entire professional life to commission submarines that were actually built.

Hawke made Labor electable and he enhanced the security of the nation. Since Hawke, Labor has had two wobbles. Mark Latham seemed for a moment so hostile to George W Bush that he might have imperilled the US relationship, which perception contributed to his defeat in 2004.

And sections of the Labor Party, especially the NSW Right, came too much under the influence of the Chinese government and of donors with links to the Chinese Communist Party. The Chinese made the mistake of thinking the NSW Right ran everything. Oddly enough, leading figures of the Left, such as Albanese and Wong, remained much more distant. Now, mainstream Labor figures from all factional backgrounds, especially those in the leadership who get security briefings, understand the nature of Chinese intelligence, espionage, political influence and military activities.

Whoever wins this election will face massive security challenges. Both sides come to the table with reasonable credibility. But that is no more than the price of entry for a searingly tough assignment.

Managing national security is the prerequisite for credible government in Australia. Scott Morrison thinks Anthony Albanese will be soft on China and too weak to stand up to Beijing. Morrison labelled Labor’s deputy leader Richard Marles “a Manchurian candidate”, an absurdity the Prime Minister quickly withdrew.