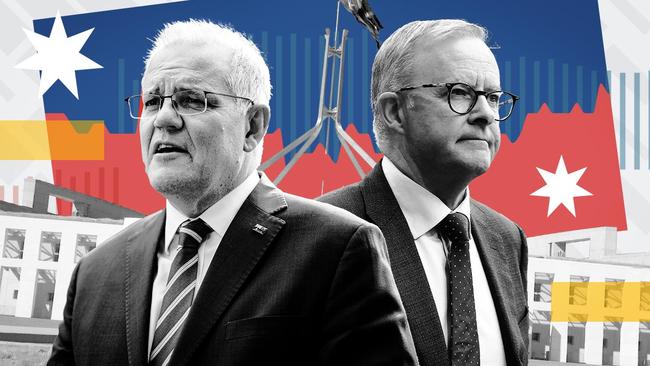

Election 2022: Albanese win will owe more to Morrison’s failures than faith in Labor

This poll will reveal if our polity has undergone a fundamental change.

Anthony Albanese awaits the final shove into history, a frontrunner throughout the campaign yet plagued by repeated blunders that highlight the pivotal issue at this poll – whether the public is ready to repress its doubts, shut its eyes and gamble on the Albanese experiment.

An Albanese victory will owe more to Morrison’s failures than faith in the Labor alternative. A Morrison victory – a second miracle – depends entirely on the undecideds falling to Morrison on the finish line courtesy of reservations about an unconvincing Albanese.

This leads to a critical consideration for the country: minority or majority government. The disillusion with the major parties and the support for independents raises the prospect of a hung parliament and a further experiment in minority government. That is a country plagued by chronic division and ineffective leadership. The polls suggest it is probably only Albanese who can form majority government.

This election will determine not just who governs – Morrison or Albanese. It will determine whether politics and the party structure are being changed fundamentally; that is, whether the Liberal Party will be politically decapitated in its once safe heartland seats, whether the House of Representatives will be reshaped by a growing crossbench of independents and whether the nation might finish post-election with a government denied a majority in either house.

Australian democracy is tested at each election and that test is conspicuous at this election. There is no great ideology contest on display, no big ideas, no compelling engagement, no leadership ingenuity. With both major parties locked into primary votes in the 30s, questions arise about the long-run future of the Coalition and Labor as political forces.

This is tied to a bigger conundrum. The policy timidity at this election is driven by fear of giving your opponent the weapons to destroy you. The power of the negative means national elections are no longer clearing houses for big ideas to deliver mandates that advance the country’s direction. Morrison’s agenda for the next term is surprisingly weak; Albanese’s is modest change but no robust reform. The engine that drives our national progress is malfunctioning. Neither Morrison nor Albanese has presented a convincing framework based on conviction.

The agendas offered at this election do not address Australia’s needs and challenges: struggling living standards, negative wages growth, weak productivity, high debt, rising inflation and interest rates, tax reform, energy transition, corporate investment, China’s assertion, defence procurement, the caring economy, industry innovation and social equity.

The national mood is hard to discern, more regionally variable than usual, different across states with both sides expecting surprise seat-by-seat results.

Yet the campaign, overall, has been more about negatives than positives, more about personalities than policies, with grievance outmatching inspiration. This is not an encouraging omen.

But let’s get the context right. In an age of banal celebrity that produced Donald Trump and dangerous populists of the left and right across many Western democracies we should be grateful for the dedicated professionalism of Morrison and Albanese with their pitch to mainstream voters and the absence of extremism in the main parties.

The public seems weary of politics yet also addicted to politics in a time of cultural confusion. Cultural upheaval has become a bigger driver of our politics and this election brings that trend to a zenith. The mass-based appeals and loyalties of the industrial age are being torn apart in the digital age as ideas of class, union, profession, religion, sex and gender are redefined in an era of social media.

There is a new progressive moralism on display in the assertion of professional women, demands for climate change ambition and the cult of the anti-corruption commission. The upshot is a far more fragmented political system.

Both Morrison and Albanese lead parties divided by competing internal values and economic interests as Australia is more fractured between regions and cities and between the post-material elites and down-to-earth battlers.

If Albanese becomes prime minister he will be subject to similar pressures that so damaged Morrison. Morrison has outcampaigned Albanese. His experience, policy command and drive has been conspicuous. But personal dislike of Morrison, often visceral from female voters, has undermined his efforts. It has been a constant management problem for the government and a perpetual reference point for Labor.

Attempting to re-position, Morrison likened his past style to a “bulldozer”, but this merely accentuated his difficulty in expressing empathy and compassion, the signals demanded by rising progressive etiquette. The Morrison “dislike factor” could be the difference in a tight result.

Albanese’s flaws have been repeatedly exposed – not knowing the unemployment rate, the cash rate and whether the borders were open – and they constitute failures beyond the accidental. If Labor loses, doubts about Albanese’s capacity as a prime minister will have loomed large.

Yet Albo’s style has a forgiving quality – in the leaders’ debates Albanese was effective in better relating to people, creating an emotional bond, projecting as a down-to-earth, unpretentious Aussie who doesn’t get everything right but is sincere and will do his best. It may be enough.

The election is a potential watershed for both sides, for their traditional voting base and loyalties and their ability to construct a viable governing coalition.

For Labor, this election is a must win. Labor can hardly tolerate another defeat, another 2019 repeat. Defeat would register three successive losses at tight polls since 2016. It would mean that at the last 10 elections it had won only one – in 2007 – as a majority government. Another defeat would cast doubt on Labor’s historic mission as a governing party in its own right.

Defeat for the Morrison government will guarantee an intense Liberal Party debate about how best to manage its so-called broad church, which is being eroded from both sides, and how to retain support from voting conservatives and progressives as the country changes.

This election was a turning point for the Australian economy – but not because of any decision by a politician. Both sides of politics were caught by a higher than expected annual inflation rate of 5.1 per cent, the strongest consumer price index in 20 years, which drove the Reserve Bank into a mid-campaign interest rate increase, damaging the government’s prospects and playing perfectly into Labor’s alarmist cost-of-living mantra.

This was a turning point, creating a wedge between the politics and economics. The election campaign rested on assumptions about a world that was disappearing. The new world is an extended cycle of interest rate increases, punishing pressure on households, rising inflation, government spending restraint and a psychological jolt for an unprepared community. The age of convenience based on near free credit, globalised disinflation and government pump-priming is dying.

Yet the campaign ended with a symbolism of powerful denial – Labor’s extra $7.4bn on the budget bottom line across four years based on a series of questionable revenue measures plus an extra $50bn in off-budget funds. Labor Treasury spokesman Jim Chalmers championed this outcome as productivity-based investments.

Given the government’s emergency spending, these numbers are modest. Yet, with a global backdrop of mounting risk, Labor’s insistence that higher deficits are the optimal response reflects the transforming legacy of Covid on Australian psychology – the crisis has prioritised compassion spending over economic reform. If Albanese wins, he faces a conflict between his rhetoric and the reality he faces.

Beyond that, Labor’s costings reflect its sense of political assertion. Every Labor decision is justified by invoking Morrison’s failures. “We won’t be taking lectures from the most wasteful government since federation,” Chalmers said.

There has been a robotic irrelevance to much of the campaign. It was largely dominated by questions and answers about outcomes that politicians cannot control – wages, inflation, cost of living, interest rates and power prices – while there was scant focus on the actual policy reforms able to shape these outcomes.

Morrison said there was “no magic pen” to make it all happen. Yet the campaign seemed a triumph of feeling over logic. The notion that good policy is good politics is long lost. Albanese and Chalmers were handed a dream campaign script in their effort to discredit the government – rising inflation, more cost-of-living pressures and real wage losses reflected in wages rising at 2.4 per cent, far below inflation.

Morrison had to concede no prospect of real wage gains for another 18 months. Albanese’s message that Labor would put people at the heart of its economy policy had to resonate.

At the end of the final week, Morrison and Josh Frydenberg were vindicated when unemployment fell to 3.9 per cent, highlighting the transformation this term with a labour market initially threatened by the shadow of the Depression but finishing with the best unemployment results since 1974. Business is issuing siren calls about labour shortages.

This outcome is fidelity to the Liberal Party’s deepest belief – jobs, growth and prosperity. Yet it is not clear whether it translates into ballot box support.

The central paradox of the last term was Morrison’s success in managing the pandemic in terms of vaccination rates, mortality rates and economic recovery while losing the politics, seeing his government outmatched in the polls and his personal standing plummet.

Morrison’s policy record is impressive in a parliamentary term of shocks and traumas defined by the pandemic, a global recession, a domestic recession, rising geo-strategic tensions, new demands on national security and China’s economic coercion against Australia. If this election were purely a question of Morrison’s management of serious challenges over the past three years the government would deserve re-election with an increased majority.

That this obvious conclusion often draws surprise and amazement testifies to Morrison’s political failures and Albanese’s political skill over the term.

In a brutal and effective tactic Albanese exploited Morrison’s blunders, beginning with the bushfires two years ago, to brand Morrison starting with the line “I don’t hold a hose” – destined to pass into our rhetorical history. The tactic worked. Morrison was branded by his enemies and has never recovered. Yet while Albanese branded Morrison for his failures the government, inexplicably, declined to torch Albanese during much of last year, choosing instead to focus on positives. Belatedly, it tried to catch up in this election campaign. If Morrison loses, the Liberals will shake their heads in disbelief at how they allowed Albanese, with his vulnerabilities, to outsmart them and get into the Lodge with nothing like the scrutiny applied to Morrison over the past 18 months.

The pandemic was Albanese’s friend – it gave him free passage while the focus lay with Morrison and the premiers.

Morrison’s related failure was conspicuous in the campaign – an inadequate agenda for the future. He invited the impression that after three terms the Coalition was near policy exhaustion. Until his formal policy launch last Sunday Morrison’s script was shaped by the past. In political terms he needed strong policy conflicts with Labor over a fourth term agenda but absent the clash over home ownership he didn’t get them.

The story of this campaign has been unusual policy overlap. Albanese had reasons for his tactic. He needed to ditch Bill Shorten’s class warfare and high-tax agendas. While Albanese invoked productivity as his mantra, his actual proposals to boost productivity look unpersuasive.

Herein lies the ultimate paradox of election 2022 – both Morrison and Albanese preach productivity but neither has their hearts in the policies to get there – witness how the Liberals, for political reasons, have run shy on enterprise bargaining reform. Morrison was far happier on Thursday when, after Labor’s costings proved it was a bigger spender, he used the line he had longed for – here was the truth about Labor: “When they can’t manage money they come after yours in higher taxes.”

The polls seem to be tightening. A close result may suggest equivocation in the public’s mind, holding reservations about both leaders and a campaign too reliant on negatives.

Election 2022 has been dominated by a nation strangely polarised yet indifferent, more certain of what it opposes than what it supports – with Australia hovering at the edge of terminating the nine-year-old Coalition government now headed by Scott Morrison.