Election 2022: a step into the great unknown

The great hesitation election is over. Not since World War II has there been a vote where so many have turned their backs on the major parties.

Not since World War II has there been an election where so many have turned their backs on the major parties, refused to indicate how they will vote and offered so much support to minor parties and independents where preference flows are entirely unpredictable. Nor have so many people voted so early.

Scott Morrison and Anthony Albanese both know it is so tight either can win, and the prospect of a hung parliament and minority government is real because of hesitation about the Prime Minister and hesitation about the Opposition Leader.

This great hesitation is understandable and explicable after almost three years of pandemic fatigue, global security threats and uncertainty, including a war in Europe, an economic recession, thousands of Covid-19 deaths, border closures, lockdowns and an election campaign where voters have been offered little more than reheated policy leftovers, platitudes and personal abuse.

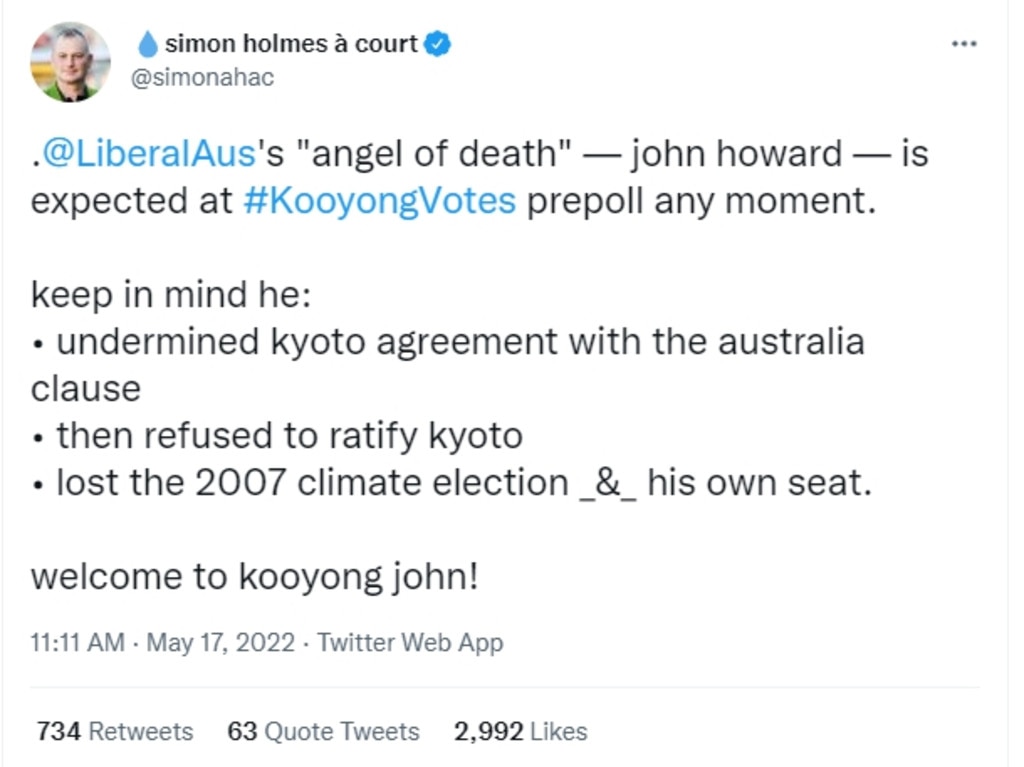

Despite Albanese and Labor being firm favourites in the polls and betting markets for months with an expectation that Morrison and the Coalition will lose, at least to a minority ALP government helped by rich climate change independents in affluent suburbs, the final week has changed the perception.

The polls and betting markets tightened and, more important, Albanese and Morrison campaigned furiously in recognition that the election would be decided in the final days, perhaps the final hours, as one in three voters decided whether they would break towards the Coalition or Labor with their undecided primary vote or preferences.

The issue for the Coalition will be whether the late break has been enough in the time available. The early polls, reports from polling booths and reading by experienced campaigners all suggest while the tightening is in the Coalition’s favour, anything from storming out of a press conference to falling over a child playing football may sway voters in making that late decision on how to vote – as they did in 2004 and 1993, both elections that favoured the incumbent despite the polls.

In the final days there has been a view that the so-called teal candidates have peaked; that the vote for Clive Palmer’s United Australia Party is stronger than expected, particularly in Queensland and Western Australia; that the Coalition is strong in Queensland and capable of winning the two seats in the Northern Territory, Lingiari and Solomon; that Labor is sure of winning the Liberal-held Boothby in South Australia; and that there are seats in western Sydney and suburban Melbourne that are in play.

This means on polling day the most likely outcome is a minority government, which would be Labor assuming independent support; then a Labor majority government with a narrow margin; and finally a majority Coalition government – which can’t be ruled out. If we know the result early on Saturday night it will be a majority government, but if not it could go for days while individual seats and huge postal and pre-poll votes are counted.

Morrison and Albanese know just how tight the election is, the key role preferences will play and the danger of surprise results, so both leaders blitzed the nation in the past week and their itinerary, despite their assertions, spelt out in large red warning letters the list of seats at risk for both sides.

Albanese went to Perth, which was a huge commitment in time for the last week, where Labor had hoped to win four seats but has now zeroed in on Swan and Pearce. He also went to the safe Labor seat of Fowler in western Sydney, where former NSW premier Kristina Keneally was parachuted in from her expensive home in Pittwater’s Scotland Island and is under extreme pressure from local independent deputy mayor Dai Le.

After a fractious few days in the media over Labor’s deficit being bigger than the Coalition’s, Albanese tried to campaign in Queensland without his travelling press pack, following highly damaging gaffes on the economy in the first week of the campaign and mounting pressures in the last week led to more mistakes and rushed corrections. He mistakenly claimed the international border was shut and floated the ludicrous ideas of not allowing for an acting prime minister while the presumed Labor prime minister and foreign affairs minister Penny Wong went to the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue meeting next Tuesday in Tokyo.

Albanese also said if counting had not been completed, Wong would go as a third wheel with Morrison to meet US President Joe Biden, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Japan’s Fumio Kishida. It added to a long list of doubts about Albanese’s grasp of serious security issues and the workings of government.

If the election result is not clear by Monday, Morrison will go to Tokyo as the prime minister and representative of Australia, pure and simple, and that’s what the other leaders are expecting according to the White House briefing on Biden’s first trip to the Indo-Pacific to discuss security in the face of Chinese aggression.

Despite the overwhelming dominance in national published polls and Albanese’s relentless and successful personal destruction of Morrison’s character, which has become the single greatest weight on Coalition support, the inevitable happened – the polls tightened as hesitancy about Albanese was almost as influential as negative feelings about Morrison. This means if the Coalition loses the election the biggest single strategic mistake will have been Morrison’s failure to frame Albanese as negatively as Labor framed him; and if Labor loses, the greatest strategic mistake will have been Albanese’s failure to build his own profile after more than 20 years in parliament and three as Opposition Leader.

The emphasis on the leaders’ character has been accentuated by the lack of policy differences, with the only real fight emerging over housing policy in the final week of the campaign as Morrison offered first-home buyers access to their superannuation funds to use as a deposit – a direct counter to Albanese’s central election promise of a taxpayer-funded scheme for the shared investment for a new home.

The absence of contrasting policy and a national shift in sentiment also mean the fights in individual seats can become hyper-localised, with the possibility of rogue results in safe seats throwing careful calculations and methodology into real doubt.

Many of the assumptions and predictions about a Labor victory – with some from the ALP looking at 80 to 81 seats in the 151-seat House of Representatives after gains of around 10 – rely on the Coalition not winning back any Labor-held seats.

To win an outright majority the ALP has to win a net seven seats, yet there are many old hands on both sides who say they can’t see the net seven because, unlike in previous elections with huge movements, it is likely the Coalition will win some Labor seats. It is the unpredictability of the preferences of the minor parties and independents – which have to be distributed for a valid vote – that adds to the uncertainty of a Labor clean sweep to power.

While the Greens’ preferences tend to be disciplined and about 80 per cent go to Labor, the preferences of One Nation are undisciplined. How supporters of the emerging Climate 200 candidates – the so-called teals in strong Liberal seats – and United Australia Party distribute their preferences is a largely unknown quantity.

In the Liberal National Party-held seat of Brisbane, sitting MP Trevor Evans faces threats on all three fronts: the lack of a federal issue has made complaints about aircraft noise a danger for him; the Greens are a third-party threat; and if the ALP finishes ahead of the Greens, preferences could give Labor a win.

In Hasluck in Perth, an early Labor target, it’s coming down to what a good bloke Indigenous Affairs Minister Ken Wyatt is; in the NT it’s law and order; NSW’s Liberal-held Bennelong could be susceptible to backlash from the Chinese community over the federal government’s stance on China; and in Labor-held Blair in Queensland it could be traffic.

This is where a great hesitancy, uncertainty, fatigue and the lack of defining policy or charismatic leadership leave the nation.

The great hesitation election is over. The refuseniks, the uncommitted, the undeclared, the undecided and the uncertain destination of pivotal preference votes will be committed, declared, decided and distributed in the poll of polls: the only one that matters.