Driven by distractions as year winds down

Having finally put his pants back on, the PM faces a delicate political calculation next week: will he promote his mini-me?

Scott Morrison was in isolation, bunkered down in the Lodge, with his official photographer of course, sitting out 14 days of quarantine after returning from Japan.

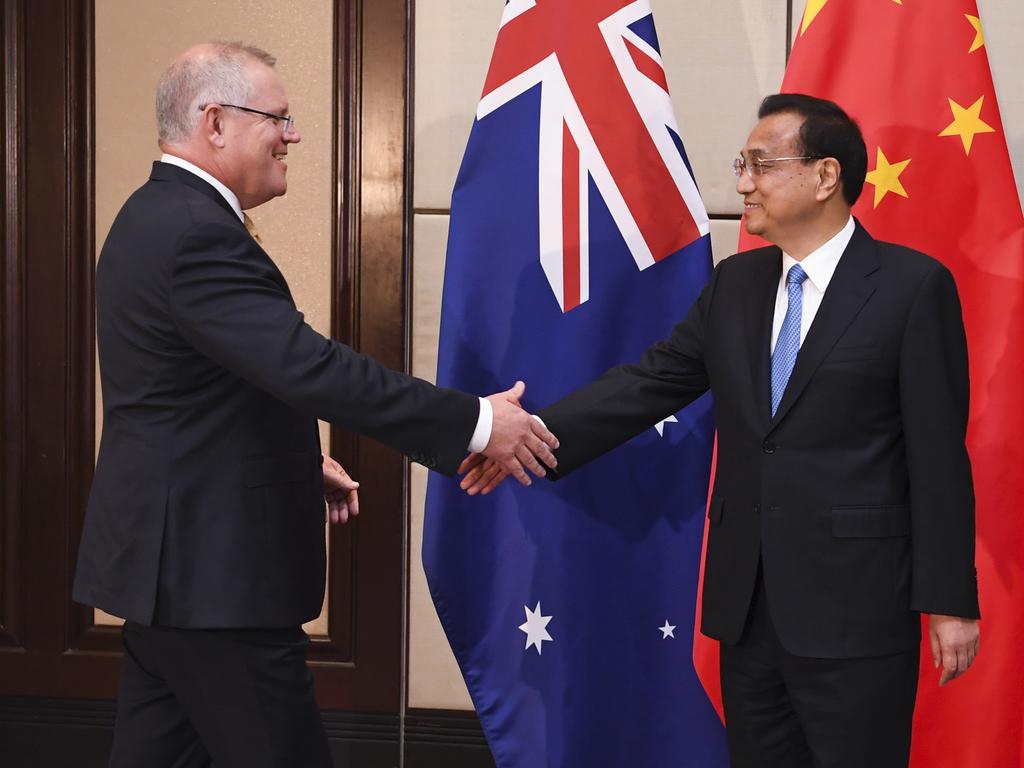

Perhaps that situation contributed to the Prime Minister’s decision to up the ante the way he did when it came to China. A Chinese foreign ministry official known for incendiary rhetoric posted an offensive fake image on Twitter of an Australian soldier slitting the throat of an Afghan child. Rather than leave it for one of his ministers to express disgust, Morrison took up the challenge, calling a media conference from iso and demanding everything from an apology to the tweet being taken down. Morrison’s political impotence in the face of a rising China was laid bare. Of course, if Morrison had said nothing his critics would have attacked him for being weak.

Because the Prime Minister wasn’t in the parliamentary chamber for most of the sitting week, Labor made the tactical decision to ignore him, directing questions at his ministers instead. This let Morrison off the hook for the robodebt debacle.

On Wednesday the official third quarter gross domestic product numbers were released, showing a 3.3 per cent bounce back in the economy. Good news, albeit off a very low base. Australia has recovered nearly half of the economic growth lost during the six-month recession, but the economy is still 3.8 per cent smaller than it was during the corresponding period last year. While Josh Frydenberg tried to paint the numbers as good news, the simple fact is the economy is hanging by a thread. A deficit of more than $200bn, debt ballooning past $1 trillion and a decade of more deficits to come is hardly good news. Throw in the trade war with China and a million Australians out of work, with millions more employed with the assistance of the JobKeeper spendathon, which runs out in March, and fragile is the best word to describe the situation.

Morrison ambled out of quarantine on Thursday, with his suit pants on this time, only to discover that China had censored his WeChat post aimed at addressing Chinese Australians directly. Not that anyone should be surprised; China is an authoritarian dictatorship with only limited respect for free speech, a free press, international law or the rule of law domestically. It murders its own citizens, it locks up journalists who don’t toe the Communist Party line and it has imprisoned hundreds of thousands of Uighurs in concentration camps. It’s a far cry from the “historic” move towards democracy Tony Abbott hailed when President Xi Jinping visited Australia in 2014.

Next week parliament sits for the last time this year; it returns in the first week of February. Labor should go after Morrison on robodebt, given the death and despair the scheme caused, as highlighted in the class action statement of claim. The Coalition set up a royal commission into the failures of Labor’s home insulation scheme during the global financial crisis, a process that cleared the government of responsibility for the handful of deaths. The deaths and devastation caused by Morrison’s decision to enact robodebt are on a scale well beyond anything that happened during the rollout of the so-called pink batts scheme.

Morrison will stonewall any demands of accountability for the failures of robodebt because he was the scheme’s architect, having conceived it as social services minister, used it as treasurer to spruik a looming surplus, and as Prime Minister fought against claims it was illegal. It was only when the government had no moves left to make that it parted with $1.2bn of taxpayer money to try to make the scandal go away.

While most Australians have been unlucky during the pandemic, Morrison has benefited from it as it took attention from his failures during the bushfires and acts as a shield from responsibility for robodebt. As Newspoll again highlighted this week, Morrison is popular and the government is ascendant: a sure thing to win the next election. It is Labor and Anthony Albanese under pressure as the year comes to an end. Which brings us back to next week’s final parliamentary sitting.

Morrison will reshuffle his frontbench once the week is over and the Opposition Leader will have to respond with his own reshuffle. Albanese may come under some pressure, with growing speculation within the opposition that were it not for Labor’s leadership rules protecting the incumbent, a move against the leader might be in the offing.

That could happen anyway, but it is unlikely next week. One senior member of Labor’s frontbench — without an axe to grind or interest in the leadership for themselves — told me Albanese can’t afford to make a misstep across the summer. Doing so could become a trigger for change, the same way Kim Beazley referring to Rove McManus as Karl Rove was used as an excuse to move against him back in 2006.

For Morrison’s part, his reshuffle is a further chance to put his stamp on the government he inherited from Malcolm Turnbull. Mathias Cormann’s departure allows for a limited reshuffle, unless Morrison wants to really shake things up, which he could do by demoting duds such as Richard Colbeck, for example.

The Prime Minister could promote the likes of Nicolle Flint or Sarah Henderson if he wants to beef-up the number of women on the frontbench. Backbenchers such as Dave Sharma and Tim Wilson are deserving of frontbench promotion, but Morrison may not value that both think for themselves and aren’t afraid to express opinions.

Perhaps the trickiest decision the Prime Minister has to make is whether to promote Ben Morton further up the ministerial ranks. Morton, a Morrison mini-me, is assistant minister to the Prime Minister. It is a role that allows Morton to work closely with Morrison, which the latter values very highly. But Morton is ambitious and unlikely to take kindly to being overlooked.

John Howard always used to say reshuffles are one of the most delicate political calculations a leader has to make.

Peter van Onselen is a professor of politics and public policy at the University of Western Australia and Griffith University.

A confluence of circumstances turned the penultimate parliamentary sitting week of the year into an unusual affair. Distractions, albeit some important ones, were the focus of attention. Next week is likely to be different.