Downfall of a monster: behind the Harvey Weinstein verdict

The Weinstein trial verdict will reverberate around the world as a dramatic and hard-fought victory for the #MeToo movement.

“I feel like the forgotten man.” For a case that always meant so much more than a single individual, Harvey Weinstein always found a way to bring it home.

In December last year, a few weeks before he was due to face court on sex crime charges — a trial that has now ended with two guilty verdicts, three acquittals and a decisive victory for the #MeToo movement that he had come to define — the fallen Hollywood producer found himself in a Manhattan hospital, still obsessing over his image and his legacy.

The problem, it seemed, was a lack of sympathy. He had been shuffling to court with a walker, a greatly diminished figure, and some people thought it was all for show. A reporter from the New York Post was summoned to the New York Presbyterian Weill Cornell Medical Centre, where Weinstein was recovering from spinal surgery after a car accident.

The producer said he had undergone a “major operation”. He then launched into a defence of his career, saying he had “pioneered” the work of women in film and that his achievements were being ignored.

The interview, then and now, was striking in its grandiose sense of entitlement and delusion. Two years and two months after Weinstein had been exposed as a serial sexual offender, cementing him as the figurehead of a backlash over misuse of power and sexual assault, there was still no sense that he had reflected on the damage he had caused.

“My work has been forgotten,” he said. “I want this city to recognise who I was instead of what I’ve become.”

When the jury handed down its verdict on Tuesday morning, Australian time, Weinstein’s fall from grace was complete. The two guilty verdicts — third-degree rape and first-degree criminal sexual act — mean the 67-year-old faces between five and 25 years behind bars. About 90 women have accused Weinstein of sexual offences, but the six-week trial was confined to a more narrow frame. The jury was asked to consider the cases of two victims: Miriam Haley, a production assistant, said Weinstein had forced oral sex on her in 2006, while Jessica Mann, a former actress, accused him of raping her in a New York hotel in 2013. Their accounts were supported by four other women who claimed Weinstein had assaulted them, including Sopranos actress Annabella Sciorra, who testified that the producer had raped her in her Manhattan apartment.

Among the other charges, Weinstein was found not guilty of first-degree rape and predatory sexual assault, which carried a maximum sentence of life in prison. His lawyers have said they will appeal, but his legal problems continue regardless. Separate criminal charges await in Los Angeles, where Deputy District Attorney Paul Thompson is “definitely proceeding” with his case. Until then, Weinstein will remain in custody ahead of sentencing in New York on March 11.

“This is the new landscape for survivors of sexual assault in America, I believe, and it is a new day,” said New York District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr, who had come under fire for declining to prosecute the producer in 2015.

“Weinstein is a vicious, serial sexual predator who used his power to threaten, rape, assault and trick, humiliate and silence his victims.”

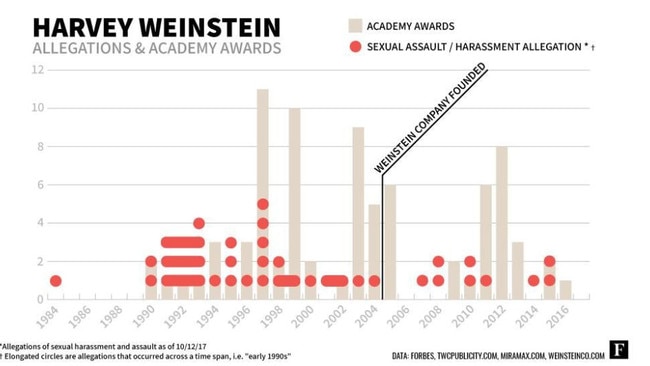

In October 2017, when The New York Times and The New Yorker published their original forensic reports, detailing a pattern of sexual assaults that spanned several decades, Weinstein’s downfall was swift. He was fired from the Weinstein Company, which he had founded with his brother Bob and which later declared bankruptcy as a result.

He was also banished from Hollywood, an industry he had once ruled with ruthless efficiency.

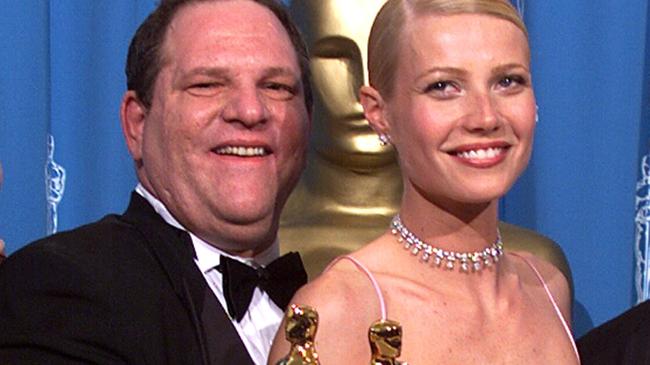

As a producer, Weinstein had overseen successful films from Pulp Fiction to The King’s Speech and Shakespeare in Love. He was said to be the second most thanked person, after God, at the Oscars.

His disgrace shook the film world to its core but also led to tough questions about power and misogyny that reached well beyond Hollywood. A profound shift was under way. The #MeToo movement had been given its name a decade earlier but Weinstein gave it a face, along with a renewed urgency for change.

Before long, tough questions were being asked about powerful figures in sport, politics and business. In the entertainment world, Kevin Spacey disappeared from view after being accused of sexually assaulting a younger actor. Comedian Louis CK became a pariah, too, when he admitted to sexual misconduct with several women. Others followed, each facing accusations of offending to varying degrees.

In this sense, Weinstein’s trial carried with it a significance that extended far beyond the details of the particulars of the case against him. If he had walked free, his acquittal would have given comfort to critics who claim the #MeToo movement had gone too far. It’s not hard to imagine how the argument could have gone: here was a campaign, an otherwise admirable campaign, that had spiralled into a zealous crusade, criminalising the blurred lines of everyday personal relationships and denying natural justice along the way. Certainly this was the line of thinking being encouraged by Weinstein’s defence lawyer, Donna Rotunno, who said Weinstein had become “a target of a cause and of a movement” that had removed “fundamental rights”.

As it was, the guilty verdicts helped to confirm the validity of this movement, even if much work remains to be done. “The story of #MeToo, of what the movement is about, is that men no longer have tacit permission to use their power or prestige to sexually access girls’ and women’s bodies,” said Ashley Judd, one of the first actresses to go public against Weinstein in 2017, in a New York Times round-up of responses on Tuesday.

Another accuser, actress Mira Sorvino, said: “Harvey Weinstein has haunted many of our lives, even our nightmares, long after he initially did what he did to each of us. We’ve finally taken that power back. We have exposed his evil.”

And another, Rowena Chiu, a former assistant at Miramax, founded by the Weinstein brothers in 1979, said the #MeToo movement was bigger than Weinstein alone: “This is certainly a moment of great encouragement and a milestone for me personally and the movement as a whole.”

One of the side effects of the #MeToo movement has been a re-examination of the work made by artists known euphemistically as “problematic”. Known in some quarters as cancel culture, it tends to minimise any distance between the creator and their creation. Artists behaving badly risk being banished along with their work.

Radio producers might now hesitate before playing the music of Michael Jackson, whose sexual offences against children were revealed in the documentary Leaving Neverland. Louis CK’s comedy, much of it built around edgy observations about sex, now feels out of step with our time. And while Spacey won an Oscar for American Beauty in 2000, it’s hard to watch that film now without feeling uncomfortable with his character on screen.

This re-examination has even called into question the work of Woody Allen, and of artists who have long since died, from Caravaggio to Picasso. In Australia, the art of Donald Friend remains a difficult proposition, courtesy of a renewed focus on his relationship with underage boys.

As a film producer, Weinstein stands perhaps one step removed from the products he backed. Even so, there has been pressure on industry figures who have profited from his talents.

Ben Affleck, whose career took off in 1997 alongside Matt Damon after they made Good Will Hunting with the help of Weinstein, has promised to donate any future royalties from such films to charity. It’s the same story from Kevin Smith, whose 1994 hit Clerks was produced by Miramax. Smith wrote on Twitter in October 2017, shortly after the story broke: “He financed the first 14 years of my career, and now I know while I was profiting, others were in terrible pain. It makes me feel ashamed.”

But there are other signs that Hollywood is moving against the standards that Weinstein helped set. At the height of his powers, Weinstein was renowned for his aggressive campaigning during awards season, forcing other companies to follow suit. A year after Weinstein’s demise, Netflix hired Lisa Taback, an awards strategist who worked on some of the producer’s Oscar-winning films, among them Shakespeare in Love (1998) and The Artist (2011). She oversaw Netflix’s campaign last year for Roma, which won three Academy awards. But this year, despite going into the ceremony with 24 nominations and a film by a living legend — Martin Scorsese — Netflix won just two awards. This might have been an aberration, the consequence of a strong field of nominees, but it could signal a broader shift all the same.

All that, though, faded into the distance this week as sexual assault victims processed the fate of a once powerful man. “Gratitude to the brave women who’ve testified and to the jury for seeing through the dirty tactics of the defence,” said Rosanna Arquette, another Weinstein accuser.

Anthony Rapp, an actor who accused Spacey of sexual assault, said: “I applaud the women who bravely stepped forward to help forever alter the conversation around what they — and all of us — have to put up with.”

Even if Weinstein hadn’t symbolised a movement, his career is finished. His reputation will never recover. His name will remain synonymous with the worse excesses of power. And if he dies in prison, unlamented, delegitimised, still protesting his innocence, still maintaining the lies that those encounters were consensual, his legacy will forever be linked to the momentum that finally gave survivors a voice.

“This case reminds us that sexual violence thrives on unchecked power and privilege,” said Tarana Burke, founder of the #MeToo movement. “The implications reverberate far beyond Hollywood and into the daily lives of all of us in the rest of the world.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout