Door open for housing hit

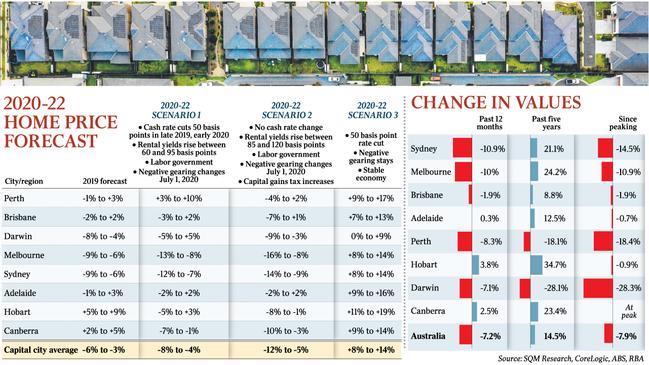

Negative gearing and capital gains tax changes are leaving home values vulnerable | How plans to shake up property will affect you.

New to downtown Chicago, I’d regularly do a double take walking past real estate agencies. That can’t be true, I’d think, looking at the ads in the window.

This is a global financial hub, a city with a metropolitan area of more than eight million people, home to one of the world’s greatest universities. Yet 130sq m apartments with two bedrooms, two bathrooms and a view of Lake Michigan are going for $US279,000 ($398,168). For about $US600,000, you can have a four-bedroom, four-bathroom townhouse next to a golf course in fashionable Lakeview, 20 minutes by bus north of the city.

The prices of equivalents in Melbourne, Sydney, even Adelaide, dwarf these, even given the 9.7 per cent fall in combined capital city prices since the 2017 peak.

Don’t get me wrong. For much of the year you can barely go outside in Chicago it’s so cold. Parts of the city are no-go zones. And the city’s population isn’t growing as quickly as back home (see previous points). But the chasm between the prices, even when the Australian dollar is weak, highlights scope for further falls in Australian dwelling prices.

And that’s before the Labor Party attempts to end negative gearing and increase capital gains tax, which it has promised if it wins government this weekend.

Negative gearing is a longstanding tax principle, almost unique to Australia, that allows losses from investments to offset wage and salary income for tax purposes. Even though Labor would grandfather existing investors — about 1.3 million taxpayers declared losses on investment properties in 2017 — housing’s appeal to new investors would suffer, sparking fears that the price of all dwellings will be dragged down.

Home prices became a central issue in the last week of the federal election campaign when Scott Morrison announced on Sunday that a Coalition government would offer first-home buyers support with their 20 per cent housing deposit, mirroring a New Zealand scheme. Under the Coalition plan, the National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation would guarantee the difference between 5 per cent of the purchase price and the 20 per cent deposit. “This will make a big difference, cutting the time taken to save for a deposit by at least half and more,” the Prime Minister said.

Wealth effect

The wealth effect — the link between net wealth and economic activity — appears to have kicked in already. Economic growth has slumped into a per capita recession after house prices began falling. From a peak of $6.6 trillion in March last year, the value of residential housing, by far the biggest component of household wealth, had fallen to $6.38 trillion by the end of the year.

Since the 1950s, economists have understood households base current spending on their lifetime wealth. When wealth increases suddenly — especially if the windfall is thought to be permanent — so does spending, and vice versa.

Until recently, homeowners enjoyed extraordinary gains. The value of household assets have surged from about six times household disposable income in the early 90s to about 11 times.

“After increasing by around 60 per cent between 2013 and 2017, growth in household wealth has slowed recently because of falling housing prices,” the Reserve Bank of Australia said recently.

The wealth surge has helped prop up household consumption, the biggest component of gross domestic product, as wage growth has been sluggish. With wages still sluggish and wealth now going in reverse, the big question is what this means for a slowing economy.

“If there are further sizeable falls in housing prices, this would be expected to result in more persistent weakness in some types of consumption,” the RBA says in its quarterly monetary policy update, released last week, widely seen as paving the way for further interest rate cuts after the election.

Falling growth shouldn’t be too surprising; the wealth effect bites quickly. A 10 per cent rise in housing wealth increases consumption by 0.8 per cent within six months, according to RBA analysis that examined movements in housing wealth and consumption in the six states from 1988 to last year.

Put another way, a dollar increase in housing wealth lifts consumption by 3c a year. Cars and household furnishings show the biggest response.

“As well as lowering net wealth and household consumption, lower housing prices also reduce incentives to build new housing. The decline in household consumption and residential construction activity reduce aggregate demand, which leads to lower business investment,” the RBA says.

Still falling

Repair work on negatively geared property worth $1.8 billion a year could evaporate, according to the Master Builders Association. “Thousands of small mum-and-dad building businesses and tradies in every city, town and region around Australia would feel the impact of Labor’s policy progressively if it is rolled out,” chief executive Denita Wawn says.

The economic bottom line is that a sustained 10 per cent fall in nationwide dwelling prices, not too different from what has already occurred since late 2017, would push up the unemployment rate by 0.4 percentage points and would reduce GDP by 1.2 per cent, the RBA says. “The macro-economic consequences of falling housing prices are smaller and less sustained when monetary policy responds,” it says.

Financial markets have priced in a further two interest rate cuts this year, which would bring the cash rate to a new record low of 1 per cent. That would lift house prices by about 15 per cent within four years, according to economists Trent Saunders and Peter Tulip. Mortgage rates have a way to go yet; in the US, 30-year fixed rate mortgages are available for under 4 per cent interest.

Falling house prices and turnover affect state government coffers, too. Three state treasurers slammed Labor’s proposed negative gearing and capital gains tax changes last week.

“The policy was bad in principle and bad in practice. It was proposed at the height of the property boom, but circumstances have changed and the policy now must change,” NSW Treasurer Dominic Perrottet says.

The Centre for International Economics estimates the states would lose more than $1.4bn a year in revenue (including $400 million in lost GST) as a result of the capital gains tax increase.

The NSW government expects to collect $200m less in stamp duty — a reduction of up to 1.3 per cent — across the three years following the change. And Labor’s negative gearing changes would reduce house prices, which in Sydney are already down 11 per cent across the year to April, by an extra 0.5 per cent by the end of this year.

US experience

In the 80s, the Chicago skyline was dotted with loss-making commercial real estate developments, many even vacant.

“It was a favourite of California doctors,” says a tax professor at the University of Chicago. High-income professionals would generate losses on real estate investments in other states to offset them against their wage, fee and salary income, which were subject to higher rates of tax.

Negative gearing in the US ended in 1986 with Ronald Reagan’s big-bang tax reform, which cut tax rates and broadened bases. The US economy and housing market survived, and ours can, too.

If people are rational and the polls are useful, the bulk of the impact of Labor’s changes must already be factored in to current house prices. Labor has been consistently ahead in the main published opinion polls and proposed ending negative gearing before the 2016 election.

If the party follows through with its promises in government, the impact should be small.

The introduction of a 50 per cent capital gains tax discount in 1999 ultimately created the push to end negative gearing, a principle of the tax code since 1915. Since 2000, the number of negatively geared investors doubled and the value of deductions more than tripled, creating an obvious target of frustration as house prices soared.

If there are benefits to home ownership, tax strategies that have the side effect of creating a growing class of landlords will undermine them. After all, the greater the share of the population that are property investors, the greater the share that are renters. For 25- to 35-year-olds, the home ownership rate has halved since the early 80s to 30 per cent.

It also would be better that investment decisions were made more on real rather than tax rules. It’s fine for taxpayers to engage in debt-funded speculation on share and house prices, but it’s a bit much to get a tax benefit that comes, in effect, from those who don’t want to so engage.

Indeed, if you can write off your investment losses against your wages, surely I should be able to deduct my rent or bus fare from my wages?

Moreover, it has done little to make housing more accessible or affordable: our house prices are among the highest and rental vacancy rates among the lowest in the world. More than 90 per cent of negatively geared properties are established rather than new.

Living with low prices

Whatever happens to negative gearing, falling house prices shouldn’t automatically spark concern. For a start, the wealth effect of falling house prices is blunted to the extent renters, about one-third of households, feel richer as a result. A recent US Federal Reserve study found falling house prices had a “negligible effect” on consumption in the US financial crisis. A slump in bank lending and financial constraints on households owing to higher unemployment had a much larger impact.

Chicago is doing fine with much lower house prices. Could it even be possible that higher land and house prices damage the economy? Higher land prices undermine economic growth, according to a recent study by Prosper Australia Research Institute: higher housing costs increase costs for businesses and workers, leaving them less to spend on genuine investment and other goods and services.

“The more producers must pay in rents or mortgages, simply in order to exist, the less remaining capacity they have to invest in future production,” Prosper’s Gavin Putland says.

The only beneficiaries of higher house prices tend to be landlords, banks, real estate agents and builders. The share of GDP attributable to workers and businesses has been steadily shrinking during the past century, gobbled up by tax and landlords.

Putland says: “Since 2003, the economic rent of land has consistently exceeded 15 per cent of GDP. The extraction of this economic rent, no less than the extraction of taxes, is a drain on the capacity of workers and employers to invest in future growth.”

Putland dismisses the wealth effect, that making landowners rich will help the economy.

“On past form, successful producers will invest their gains in further production, while successful rent-seekers will invest their gains in further rent-seeking,” he says.

The fall in prices in Sydney and Melbourne probably has prompted a sharp fall in new home approvals, as local governments, dominated by property owners curb development to prevent prices falling too much further.

In Chicago, by contrast, aldermen have veto over all developments within their wards, practically ensuring corruption on the one hand and ready supply of new homes on the other.