Don’t fret: Our economy is growing

Our economic conditions are softer than many would prefer, but all is not lost.

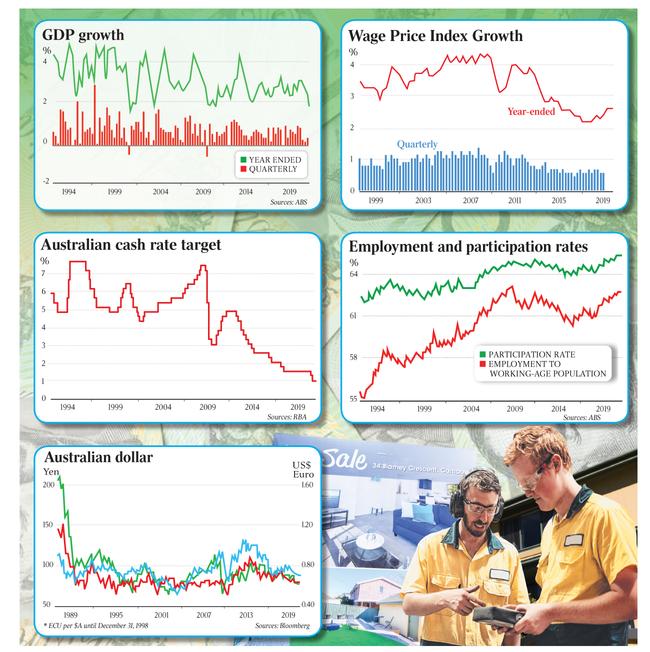

There is a lot of wailing and gnashing of teeth about the state of the Australian economy. In many ways this is strange given that economic growth remains positive, the rate of unemployment is relatively low by recent historical standards and the proportion of the working-age population in work is extremely high.

There are two principal reasons there is seeming widespread concern about the outlook.

First, there is the uncertainty in relation to the world economy and the potentially negative disruption caused by the trade dispute between the US and China. In this context, it has to be acknowledged that world trade is growing at its lowest rate in a decade, since the global financial crisis had a seriously adverse impact on world trade flows.

The second reason behind the widespread apprehension about the economy relates to several economic variables. The sluggish growth of wages, which has been apparent since 2014-15, the high rate of household indebtedness and the very low growth in productivity are factors that concern expert economists and the population at large.

The data that was produced recently by the University of Melbourne using the results of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey revealed that real household incomes have been essentially flat since the GFC. Many families are keeping their heads above water, financially speaking, as a result of higher rates of female workforce participation.

The key question is: where is the Australian economy really heading during the next year or two? Even though the Reserve Bank of Australia recently reduced the expected rate of economic growth for this year — from 2.75 per cent to 2.5 per cent — governor Philip Lowe is inclined to the view that the economy may be close to a positive tipping point. The RBA now is projecting gross domestic product to grow by 3 per cent, up from 2.75 per cent, in the year ending June 2021.

Jobs dilemma

One of the central conundrums when assessing the Australian economy is the strength of the labour market. Were the economy to be in serious trouble, we would not expect employment growth to be so strong and the rate of unemployment to be in the low 5s.

On the most recent figures, the number of employed people grew by 2.6 per cent across the year ending in the June quarter, with full-time employment accounting for most of the new jobs. To be sure, the strong labour demand has been accompanied by a strong labour supply response, with workforce participation rates at historic highs. Female participation, in particular, has soared.

If we look at where the jobs have been coming from, we note that education, health and social assistance have been particularly significant. Other parts of the economy are failing to create jobs — indeed, there have been job losses — and these include parts of private sector construction and the retail trade. The combination of strong employment growth and sluggish GDP growth translates into poor productivity growth. As the Reserve Bank notes: “There has been little growth in non-farm labour productivity over the past three years.”

Remains of the pay

A key economic variable often mentioned in the context of the state of the economy is low wage growth. Considering the Wage Price Index, it is clear the annual rate of growth began to subside about 2014-15. Annual growth rates of about 2 per cent a year are the new norm, with the growth of public sector pay rates outstripping private sector wage growth. The year-on-year WPI figure released yesterday remained flat on 2.3 per cent.

Mark Wooden of the University of Melbourne makes the point that the WPI is not an accurate representation of what individual workers have experienced in terms of their wage or salary changes. If we add in annual increments as well as promotions, it is common for many workers to have experienced wage growth of 3 per cent to 4 per cent a year.

There is no consensus as to the reasons the growth of wages has fallen so markedly in the past several years. Bear in mind that low wage growth is an international phenomenon and so it is important that some common global factors be considered. Low productivity and new technologies, particularly artificial intelligence, are often cited in this context.

There is an argument that the declining influence of trade unions is partly responsible for sluggish growth in wages. It is true that the proportion of workers who belong to trade unions continues to fall — it is below 10 per cent in the private sector — but RBA research points to a steady number of union-sponsored enterprise agreements, notwithstanding declining unionisation.

The real point here is that inflation has been very low for some time — below the Reserve Bank’s target of 2 per cent to 3 per cent a year. So real wages have still been growing. And given the backdrop of very low or no productivity growth mentioned above, it’s not surprising that low wage growth has been a feature of our economic conditions for some time.

All-consuming doubt

Consumption is the largest component of GDP and so how consumption grows is significant in terms of how the economy is growing. Given the high levels of household indebtedness and, more recently, the weakness in the housing market — which has been partly reversed in recent months — it comes as no surprise that growth of household consumption has been relatively sluggish.

Across the year ending in the June quarter of this year, household consumption grew by only 1.8 per cent. Spending on furnishing and household equipment as well as on new cars has been particularly slow to grow.

The recent decisions of the Reserve Bank to reduce the cash rate by 50 basis points in June and last month were intended to stimulate household spending, among other things. The premise is that debt will become cheaper to service and households will use the additional income to ramp up consumption.

This outcome is not certain, however, in part because many households continue to service their mortgages at the same rate — monthly repayments remain unchanged — and lower interest rates just contribute to a faster repayment of loan principals.

There is also the possibility that consumers are spooked by such low interest rates — they are as low as they have ever been — and may interpret them as indicating that a serious economic emergency exists. In this case, consumers may react perversely by increasing their savings to deal with a potentially worsening economic situation.

World of difference

Australia is a relatively open economy with a comparative advantage in the export of resources and agricultural products. International education and tourism are also important sources of export income.

One of the equilibrating mechanisms that can kick in when the economy slows — and in this case there are externally disruptive factors such as the US-China trade war and now the protests in Hong Kong — is a depreciation in the currency. This occurred for Australia during the GFC and we are now seeing a substantial depreciation of the Australian dollar, with the rate to the US dollar the lowest it has been for a decade.

The immediate impact of the lower Australian dollar is to make our exports more competitive, which in turn can contribute to stronger GDP through the net export (export minus import) sector. To be sure, Australians bear a burden through higher import prices, making much overseas-sourced online shopping more expensive. Overseas trips also cost more when the Australian dollar falls.

The cuts to the cash rate implemented by the Reserve Bank also serve to depress the currency — relative interest rates play a role in setting the value of currencies — so there is a high degree of complementarity in the monetary policy setting.

Surplus requirement

Given the recent disappointing but not disastrous GDP results, it is not entirely surprising that some commentators have called on governments, particularly the federal government, to “do more”.

In particular, the argument is made that the return to budget surplus, which is on the books federally for this financial year, should be sacrificed to ramp up the economy in the short term. Measures that are mentioned include increasing the Newstart Allowance and spending more on infrastructure. Josh Frydenberg has resisted these calls.

The Treasurer is on solid ground. For one thing, several stimulatory measures are already included in budgetary policy, such as the recent round of income tax cuts. Moreover, there is already a substantial pipeline of infrastructure projects contained in the budget. To ditch the promise of a return to surplus also could have unpredictable and adverse consequences in financial markets.

In any case, the Reserve Bank notes “strong growth in public demand has continued the recent trend of contributing a larger share of economic growth as private demand has slowed. Public demand increased … by 5.5 per cent … over the year … Public investment, which includes spending on infrastructure and public buildings across all levels of government, grew strongly over the year.”

The point also needs to be made that fiscal stimulatory measures work against the accommodative impact of the exchange rate. All other things being equal, higher government spending will push up the Australian dollar, thereby dampening the growth of GDP.

Soft spot

There is no doubt that our economic conditions are softer than many would prefer, including the Treasurer. There are plenty of overseas headwinds and equity markets are being buffeted by these headwinds, making life very uncertain for investors, including retirees. But it is hardly GFC stuff.

The economy is still growing, the labour market continues to perform strongly and housing prices appear to be rebounding. The Reserve Bank has acted aggressively and there are some signs that the economy is responding positively. The lower value of the Australian dollar is contributing to the improving outlook.

Many of the points of discussion about how productivity growth can be lifted and which would lead to higher wage growth are medium-term in nature. It is important that such discussion takes place and action is taken, but most of the measures — industrial relations reform, for instance — will have an impact only across a longer timeframe than the next year or two.

In the meantime, there are reasons to be cautiously optimistic about the near-term outlook.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout