Donald Trump’s new rules for an old war

Donald Trump puts a dollar value on everything, even conflict with Iran.

Even though we knew operatives of the Quds Force — the external covert action arm of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps — were inside Iraq mentoring and sponsoring terrorist and militia groups, and even though our troops were being killed regularly by Iranian-manufactured rockets and improvised explosive devices, we never directly attacked the Iranian operatives themselves.

Coalition forces aggressively killed and captured Iranian proxies, including militias such as the Badr Organisation and terrorist networks such as the so-called Special Groups. But we never deliberately targeted the Iranians themselves. On the contrary, Western and Iranian diplomats negotiated with each other and our forces periodically co-operated on common interests, such as the defeat of Sunni extremists like al-Qa’ida.

For their part, Iranian covert operators used their proxies to kill US troops and launch rockets and mortars against allied bases, but rarely if ever took up arms themselves against American or coalition personnel. The only time I can personally recall them doing so was in early 2007, when a Quds Force team kidnapped and killed American advisers in the town of Karbala in southern Iraq, in retaliation for a Special Forces raid targeting an unofficial Iranian consulate in the Kurdish city of Irbil. On another occasion, we captured several Iranians (almost certainly Quds Force members) during an operation against Shia militia, only to release them as soon as their identities emerged.

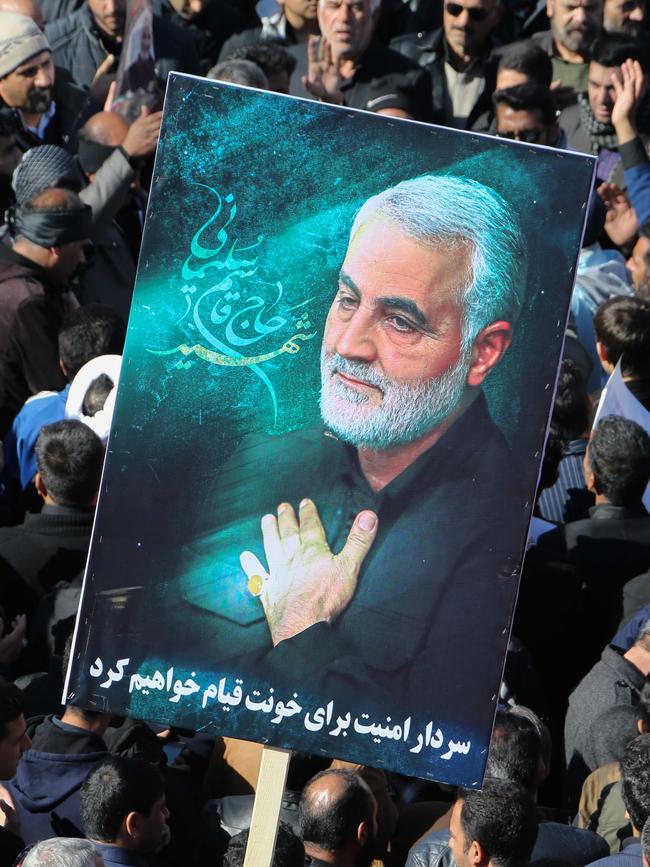

Later, during Islamic State’s blitzkrieg in 2014, the head of the Quds Force, Major General Qassem Soleimani, and numerous Iranian advisers operated openly with impunity all over Iraq, meeting senior Iraqi politicians, visiting the frontlines and co-ordinating with the Iraqi military and Kurdish Peshmerga. During the decisive battle of Mosul in 2016-17, the Iraqi army and Peshmerga co-ordinated their advance (and at times co-operated closely) with the successors to the Special Groups and the Iranian-backed militias, now known as the Hashd al-Shaabi, the Popular Mobilisation Forces, funded and trained by Iran though nominally under the control of the Iraqi ministry of defence. American artillery and coalition warplanes even occasionally supported the PMF as they fought Islamic State.

Against this background, the events of last week are a stark departure from past norms. On January 2 we saw a US drone directly target Soleimani, in company with a senior PMF commander — and on the grounds of Baghdad International Airport, no less. The strike went in less than a kilometre from the Faw Palace, the former coalition headquarters at the airport. For Americans to directly kill an Iranian general, and Iran’s most famous and influential general at that, was a major break. Likewise, Iran’s retaliation, launching missiles directly from Iranian territory against US bases, without hiding behind proxies, then openly acknowledging the strike, shows both sides are playing by an entirely new set of rules.

Much of the reaction to this week’s events has been framed in terms of escalation/de-escalation. But there are reasons to be wary of that strategic framing, and evidence suggests that far from de-escalating, the long twilight conflict between Iran and the US has simply entered a new phase, defined by this new set of rules.

What some observers have interpreted as escalation versus de-escalation — the start of World War III, versus pulling back from the brink of conventional conflict — may, in fact, be a different type of engagement altogether. What we may be seeing here is a struggle by each party to contain the conflict within the domain where it is strongest. For Iran, this is asymmetric military action via its multiple proxies; for the US, it is economic.

I have used the escalation/de-escalation framework myself to interpret events, since the killing of Soleimani more than a week ago triggered Iranian missile strikes on US bases and raised fears of yet another major war. Iraqi Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi, NATO chief Jens Stoltenberg, British PM Boris Johnson, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu all framed things the same way. President Donald Trump did too, when he said that “Iran appears to be standing down, which is a good thing for all parties concerned and a very good thing for the world”. The same mental model informs media mentions of “brinkmanship” and relief at “stepping back from the cliff-edge of war”.

But, on reflection there are at least three reasons to be cautious about this. The first is that escalation/de-escalation actually does a pretty poor job of explaining what is going on. The same partisan Democrats and media commentators who spent the past two weeks painting the President as a wild-eyed warmonger have also been deriding him as a feckless ditherer since June, when he called off a retaliatory strike after Iran shot down a US drone in the Arabian Gulf, failed to respond when Iran launched missiles into Saudi Arabia in September, then ignored the swarming by Iranian fast-attack boats of the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln in the Strait of Hormuz in early December.

It’s easy to imagine the President being muddled and ill-informed — there has been more than enough confusion and mixed messaging to go around — but it’s highly unlikely that he would simultaneously be both eager for war and anxious to avoid it, both pursuing any pretext to start a conflict, yet simultaneously willing to ignore a string of increasingly aggressive provocations from Iran. There is a better explanation for his behaviour, which I will get to shortly, but in the meantime the second reason for scepticism is that we still don’t know the full story.

The most obvious loose end is Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752, which crashed in flames shortly after takeoff from Tehran — a few hours after the Iranian strikes — killing all 176 people on board. Oleksiy Danilov, secretary of Ukraine’s National Security Council, said that “a strike by a missile, possibly a Tor missile system, is among the main (hypotheses) as information has surfaced on the internet about elements of a missile being found near the site of the crash”. US intelligence officials have said they believe the airliner was shot down by Iran; the Iranians deny that claim, while refusing to surrender the aircraft’s black boxes to the US or Boeing, the plane’s manufacturer.

The Tor, known to NATO as the SA-15, is a Soviet-made surface-to-air system designed to destroy aircraft and incoming precision missiles. Iran has 29 of them and, while details are still sketchy, it’s reasonable to assume Iranian air defences were on high alert around Tehran at the time of the Iranian missile strike, in anticipation of US retaliation.

This does not, of course, mean the downing was deliberate: accidental shoot-downs of airliners are, sadly, not that uncommon, with Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 in 2014 only the most recent of several examples. Qantas and other airlines have since re-routed away from Iranian airspace but it’s entirely possible that, immediately after the strike, with commercial aircraft still transiting Iranian airspace, a keyed-up operator (or, more likely, an automated radar system) mistook the Ukrainian airliner for a hostile aircraft or missile. The bottom line is that we still don’t know — the crash might merely have been a tragic coincidence, as Iran claims.

Another intriguing loose end is a series of events on the US northern border last weekend, when many Iranian-Americans and Iranian-Canadian dual citizens were detained (or merely delayed, depending on whose story you believe) as they entered the US from Canada. Shortly after Soleimani’s killing the US Department of Homeland Security warned of cyber-attacks, sabotage and assaults by “sleeper cells” from Iran’s ally, Hezbollah, or from the Quds Force.

Quds Force is known to make extensive use of Iranian communities worldwide (often without their knowledge) as cover for its operatives, while Hezbollah has a presence in Canada and Latin America, and both organisations have operated inside the US. The US Department of Homeland Security is now at a higher alert than a few weeks ago, while several US cities have raised their threat warning levels.

This highlights the third reason to be wary of the escalation/de-escalation framing; namely that escalation can be horizontal as well as vertical. “Vertical escalation” means increasing intensity or lethality in any one geographical area or field of activity — an arms race among rival powers is the classic example. “Horizontal escalation”, on the other hand, means expanding the arena of competition or conflict, with or without increasing intensity in any one location or domain. Examples of horizontal escalations include when al-Qa’ida in Iraq launched suicide bombers into Jordan in 2006, Richard Nixon expanded the Vietnam War into Cambodia in 1970, or the Arab nations employed the “oil weapon” after the 1973 Yom Kippur War to punish countries that supported Israel.

In this case, Iran might escalate horizontally using proxies such as Hezbollah, its Iraqi or Syrian militia proteges, hackers, organised crime networks or its Palestinian ally, Hamas, to launch deniable, or at least ambiguous, attacks on military, economic and political targets. Hours after Trump’s speech on Wednesday, several Katyusha rockets fell in the Baghdad Green Zone, likely launched by Iranian-backed militia. Similarly, Quds Force sleeper cells could mount asymmetric attacks in Europe or elsewhere.

One of Trump’s distinctive characteristics is a tendency to weaponise economics while treating military issues in strictly financial terms. His financial framing of military matters is clear from his continual complaints about NATO nations not spending their fair share, his emphasis on the cost of joint exercises with South Korea, his insistence last November that Tokyo quadruple its payments for the presence of US troops in Japan and most recently his response to the Iraqi parliament’s call for US withdrawal, when he said: “We have a very extraordinarily expensive airbase (in Iraq). It cost billions of dollars to build. Long before my time. We’re not leaving unless they pay us back for it.”

On the flip side, his preference for achieving security goals through economic means — sanctions, tariffs, trade restrictions and import controls — rather than military action is equally clear.

The “maximum pressure” campaign, Trump’s signature policy against Iran in the two years since he exited the 2015 nuclear deal, has been largely economic. It has severely damaged the Iranian economy, which contracted 9.5 per cent in 2019 and is projected to shrink by 20 per cent this year. Unemployment, inflation and lack of access to global markets are pressing problems for Tehran as its population chafes under sanctions, with deadly anti-government street protests in recent weeks.

By contrast, Iran has capable missile forces, naval units within easy striking distance of the critical Strait of Hormuz, and a regional network of proxies and proteges, giving it a far stronger hand to play in the military rather than economic domain.

On the economic front, the US (as Trump pointed out this week) no longer relies on Middle East oil, dwarfs Iran economically, and has been pressuring trading partners to cut ties to Iran. The US suffers nothing from Iran’s economic exclusion and can keep this up forever.

In this framing, rather than a string of escalatory provocations, Iran’s military moves over the past year amount instead to a series of increasingly desperate attempts to change the terms of its competition with the US to move away from the economic domain where it lacks leverage, into the military space where it has a much stronger hand.

And Trump’s refusal to respond to Iranian provocations in military terms reflects an insistence on keeping the conflict economic, bringing US financial strength to bear and avoiding the asymmetric warfare at which Iran excels.

In effect, for at least a year now, Iranian leaders (including Soleimani) have been trying to wriggle out of the “economic” box and into the “warfare” box, while Trump has repeatedly (and for the most part calmly) insisted on putting them right back in. This explains Iran’s seemingly self-destructive insistence on targeting US drones, then ships, and now troops on the ground, while also explaining Trump’s reluctance to respond in kind, even while cranking up the economic pressure (as he did again this week, announcing fresh sanctions in response to the strikes).

If I am right, if the rules are different now, and this is not a de-escalation but rather a shift from a contained regional confrontation to a broader one, then the implications are stark.

On Iran’s part, we are likely to see a horizontal escalation of asymmetric attacks. This could include attacks on Israel or on Jewish individuals, business interests and diplomatic missions in Europe, Africa and Latin America. It could include cyber-warfare against critical infrastructure, including financial systems, in the US and allied countries, kidnappings and assassinations of US and pro-US individuals, and increasing use of proxies such as Hezbollah and Hamas to carry out attacks. And it could involve a spike in bombings and rocket attacks against US troops worldwide, as well as attacks on American diplomats, aid workers and tourists around the globe.

For Washington, while economic pressure is likely to remain the weapon of choice, diplomatic efforts (such as Trump’s call this week to expand NATO into the Middle East) and increasingly direct and lethal attacks on Iranian personnel are likely. Trump, in this interpretation, would still seek to avoid major war with Iran — not because he is necessarily weak-willed or feckless, or solely because his electoral base (and virtually all Americans) is viscerally repelled by the prospect of yet another war in the Middle East, but because US economic pressure appears to be working, and while this is the case there is no upside to a large-scale military conflict. However, the new rules suggest the gloves are off and US forces will be increasingly willing to kill Iranians directly, and vice versa.

All this may yet lead to a major conventional war. The Trump administration is famously chaotic, and such a complex game may be beyond its capacity, especially under the stress of impeachment. And there is a relentless escalatory logic to warfare, one that becomes extraordinarily difficult to control once enough lives are lost.

Meanwhile, Iran may be a rational actor, but it is not a unified one. There are multiple factions and power centres in the Islamic Republic, and its proxies and allies — including those far down the food chain seeking to impress their mentors or paymasters — are liable to take matters into their own hands with deadly effect. If, indeed, Flight 752 was accidentally shot down, the tragic loss of innocent lives on board the airliner may turn out to be only the first of many lethal unintended consequences.

David Kilcullen is a former lieutenant-colonel in the Australian Army and was a senior adviser to US General David Petraeus in 2007-08, when he helped to design the Iraq war coalition troop surge. He also was a special adviser for counterinsurgency to former US secretary of state Condoleezza Rice. He is the author of Blood Year: Islamic State and the Failures of the War on Terror (Black Inc).

When I served in Iraq in 2006, and again in 2007, there were clear (albeit unwritten) rules of the game.