Does the pandemic mean the end of Big Australia?

The closing of the border and the flight of temporary visa holders will lead to the first migration outflows since the end of World War II.

The closing of the border to tourists and foreign students, and the flight of temporary visa holders to home countries will lead to the first migration outflows since the end of World War II.

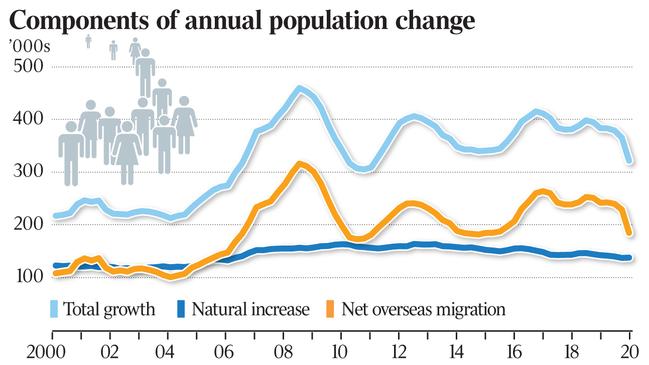

Net overseas migration has been the main driver of population for two decades, having run at an annual average of more than 200,000 for the past decade. The net loss this financial year is forecast to be 72,000, followed by a 22,000 deficit in 2021-22.

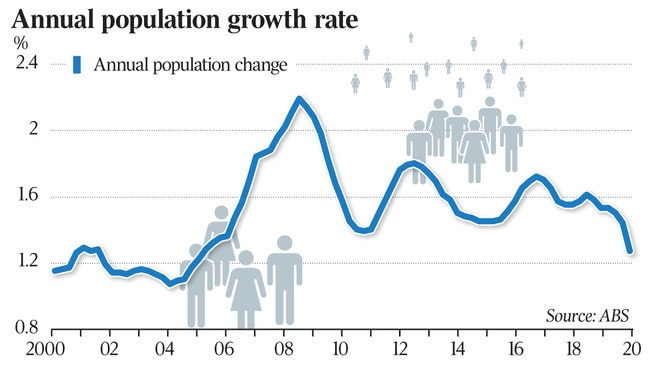

With falling fertility, our population will grow by a mere 0.2 per cent, the slowest rate in more than 100 years. The economy will be permanently smaller. Inner areas of Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane, magnets for students and working holiday-makers, will be depopulated. Australia will age a little faster.

In recent years, that combustible “P” in the trio of economic engines – the others being participation and productivity – has been the rocket fuel for gross domestic product.

Analysis by Inquirer shows that in the five years before the pandemic hit Australia, GDP increased by a cumulative 12.4 per cent but GDP per person rose by only 4.6 per cent.

COVID-19 has wiped away all per capita gains. We are back to September 2014 levels. But the overall economy is 8.8 per cent larger, as is our population.

Big Australia, the express train of world-leading 1.5 per cent-a-year population growth, is in the yards for maintenance. The pause, however, will leave a long tail, and it has the potential to change our social fabric, fiscal stability, land use and infrastructure planning, economic dynamism and political order.

This opens the field for a reset on population policy, which has de facto been immigration policy. A more open and intense debate looms. On one side are some who see high immigration as ecologically unsustainable, a threat to our social cohesion or as a “Ponzi scheme” to perpetually pump up our market size.

On the other is an established pro-growth coalition of big business, property developers and globalists, including the policy wizards at Treasury and the Reserve Bank, a majority of MPs and, since 1964, the custodians of this newspaper.

According to Gary Banks, former chairman of the Productivity Commission, people often talk at cross-purposes when debating immigration policy. “One finds time and again a failure to distinguish immigration’s effects on the economy as a whole, from the effects per person or household,” he tells Inquirer. “Immigration obviously increases the size of our population and thus our economy. But it need not raise the incomes or living standards of the existing population. And that should be the primary goal, at least in economic terms.”

And while we’re on those “famous 3Ps”, Banks says they are often wrongly used to suggest that population, the first P, is as important to growth as the other two.

“That has some validity on the aggregate numbers,” says the professorial fellow at the Australia and New Zealand School of Government, where he was once chief executive and dean.

“But in per capita income terms, empirical studies by the Productivity Commission and others have repeatedly found that the gains from immigration are small and largely skewed to migrants themselves. And that’s without considering environmental and other negative impacts.”

Over the past two decades, elevated immigration has occurred with barely a murmur, even though issues such as congestion, environmental degradation and social cohesion occasionally bubble up. The focus for voters is the permanent migrant intake, which the Morrison government last year cut from 190,000 to 160,000 for four years.

But it is the temporary stream of students, short-term workers and tourists that has supercharged the numbers.

Demographer Bob Birrell says an “enormous swath of people are in favour of less migration”. “The reason why Australia’s big migration program has not run into ballot box problems, unlike much of Western Europe and the US, is that so far political elites here have continued to support the policy, thus giving voters no place to go except fringe parties,” he says.

In a recent paper for The Australian Population Research Institute, Birrell and Katharine Betts argue this is a “fragile situation” and voters, especially non-graduates, are hostile to a revival of a Big Australia in the context of job losses and migrant competition for available work.

The authors point to a shift in the Coalition, shown by internal support for Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton’s harder line on immigration policy.

Tougher tests for citizenship and more meticulous selection of migrants have led to a lower intake of permanent migrants. As well, in May, Labor’s home affairs spokeswoman Kristina Keneally proposed lower immigration and an “Australia first” hiring policy.

The hiatus may be the best chance for “sustainable population” advocates to tap into popular sentiment amid a nation scarred by high youth unemployment, industry disruption, rising business failures and falling fertility. But it is equally an opportunity to get more control of our migration program and policy transparency; for governments to explain what they are trying to achieve and why, and to attract more high-end talent in areas where we lack ballast and to refurbish our economy for an evolving strategic and trading environment.

According to the first annual statement of the federal government’s Centre for Population, based in Treasury, the pandemic means our population will be 1.1m smaller than our pre-crisis trajectory, or 28.8m instead of 29.9m by mid-2031.

So we are three years behind where we would have been. There will be short-run and medium-term consequences, for rents and home values, especially in capital cities, where the population will be 5 per cent smaller than previously anticipated. Planners will adjust, as will a host of markets.

Put those new Woolies, Bunnings and Harvey Normans on hold. Ditto the birthing centre at a suburban hospital. Maybe the fresh rail link will not be as well patronised for the first five years. The Morrison government’s housing affordability adviser expects a temporary excess of almost 200,000 homes built over the next two years, easing the burden on renters.

According to Treasury secretary Steven Kennedy, the pandemic is projected to lower our potential output growth in the near term by affecting all three supply-side Ps that drive growth.

“Lower population growth needn’t lead to lower income per person; however, a smaller and older population may require governments to reconsider how taxation is raised to support essential services,” he told a Senate committee in October.

A medium-term review by the Parliamentary Budget Office says at the end of the decade net debt will be four per cent of GDP higher than it would have been otherwise because of the permanent impact of lower migration on population.

Our economy and tax take will be smaller with a larger underlying cash deficit.

One-time productivity tsar Banks says that when he was treasurer, Scott Morrison publicly defended historically high immi-gration by citing Treasury calcu-lations of how much tax revenue would be foregone with lower numbers.

“That is a pretty narrow way of looking at immigration, to put it mildly,” he said. “It ignores the cost side of the equation for a start.

“It ignores the capacity of our economy and society to absorb migration running at more than twice the rate Treasury itself had previously projected. More people obviously require more infrastructure and more services.

“Those costs are largely borne by the states. But that does not mean they should be ignored.”

So-called “endogenous growth theory” has it that population itself drives innovation and entrepreneurship. Treasury accepts the dynamics around migration – growth, congestion, productivity and ageing – are a “complicated calculus”. Still, it argues that a higher level of immigration tends to lead to higher productivity because a lot of the migrants we bring in are high-skilled migrants.

Morrison government ministers habitually draw on Treasury research to argue that we have each, on average, become wealthier because of our population settings. Treasury estimated one-sixth of our per capita wealth over the past 40 years was due to population factors.

Former productivity tsar Banks argues the most important Ps for living standards are participation and productivity.

“To the extent that migrants are more highly skilled than locals in areas where these are needed, then of course that should help our overall productivity performance,” he says.

“But there are questions as to whether in practice migrants have been meeting that test. Indeed there is some evidence that the definition of ‘skill’ has got more elastic and permissive over time. The surge in the skilled immigration over the past decade coincided with a slump in Australia’s productivity performance, which also is not encouraging.”

The Grattan Institute has reported that since 2005, the number of net skilled permanent migrants coming to Australia each year has settled at about 30,000. Yet the number of temporary unskilled migrants has grown from about 400,000 to 800,000 just before the pandemic. Adding skilled temporary migrants has that number rise to close to 1m.

Victorian Labor MP Clare O’Neil believes this “radical transformation to our immigration program happened without a White Paper, without a policy process, and without a national discussion”. “We need to take a step back,” says the opposition spokeswoman on innovation, technology and the future of work.

O’Neil argues that recruiting the best and brightest workers as permanent residents and citizens, such as technology entrepreneurs, has to be a priority to rebuild the program so that it has broad support and serves as a catalyst for economic transformation.

“Turning the high immigration tap on again after the pandemic without changing immigration policy would be a tremendous missed opportunity,” she says.

Stephen Kirchner of the United States Studies Centre also sees the pandemic as a chance to attract global talent, from Hong Kong for instance, but believes an immediate priority should be scaling up managed isolation and quarantine capacity, and reopening borders with COVID-free neighbours.

More boldly, the director of the USSC’s trade and investment program is arguing for a step-up of the immigration program, including the family component. The planning cap of 160,000 permanent migrants should be set aside indefinitely as non-binding in the short-run and too restrictive for the post-pandemic world.

“In the long run, the government should allow the size of the permanent migration program to self-regulate based on current and prospective labour demand and the level of wages in the targeted skill and occupational categories,” Kirchner writes in an October paper that urges policy makers to avoid the US’s demographic stagnation.

“Rising wages due to shortages in segments of the labour market will attract, while falling wages reflecting excess supply will deter prospective immigrants, although the absolute level of wages relative to overseas may dominate wages growth in attracting prospective migrants. The market is more likely to send the right signals about prospective shortages or a surplus of skilled workers.”

Then there’s the challenge of our ageing population. Migrants are younger; the ones who come via the permanent skilled program pay tax and don’t put a strain on health services. Migrants from China and India have a median age of 34, the same as people born in Australia.

As Treasury’s deputy secretary Jenny Wilkinson told Senate estimates in October, at some point migrants retire: “But, in the intervening period, they can make a pretty significant contribution to growth. At the same time, younger migrants also tend to have higher fertility levels or at least they offset the lower fertility levels of non-migrants in Australia.”

TAPRI’s Betts argues that if the aim of policy is to slow down ageing, then boosting fertility through family-friendly policies is a superior path. “If we are serious about trying to minimise demographic ageing, supporting the two-child family is nearly four times as cost-effective as are high levels of net overseas migration,” she says.

For instance, based on the latest official projections, with nil net migration and an annual total fertility rate of 1.65, the median age would rise from 37.5 (in 2017) to 49.8 in 2066. But if fertility rises to 1.95 and stays at that level it yields a median age of 45.8 in 2066, at the cost of adding an extra 2,530,154 people, or 632,539 for every additional year of youthfulness.

“If despite this the policy of high net overseas migration is pursued, the law of diminishing returns sets in. That is, the cost in terms of numbers of people added for each additional year of youthfulness increases as net overseas migration increases,” says Betts, whose calculations are set out in a March research paper, Demographic ageing: time-bomb or breakthrough?

Naturally, congestion takes centre stage in any discussion of Big Australia. Treasury’s Wilkinson told Senate estimate “congestion is about there not being the right sort of infrastructure in place at a point in time”.

Data, better planning and delivery can get government ahead of the game. For years, federal and state governments dropped the ball, wittingly and unwittingly, with inadequate land-use planning, sub-optimal infrastructure pricing and lack of local big-project capacity.

Some politicians feared “build it and they will come”. They came anyway. NSW and Victoria are delivering new roads, rail, tunnels and public transport, but at huge costs compared with overseas projects. While there is a lot of talk about “congestion busting” by politicians and new bureaucratic architecture to get better co-ordination and funding right between the three levels of government, Kirchner sees a risk in state government capture of federal immigration policy.

Kirchner argues that the government’s policy to try to divert migrants to the regions is counter-productive, leading to less dynamism and weaker productivity growth.

“People are more productive and better compensated in big cities due to agglomeration effects. Talent tends to cluster in cities where migrants can take advantage of proximity to those with complementary skills,” he writes.

As well, Kirchner says selling immigration to the electorate will be made easier if the government connects the benefits of population growth to national security imperatives arising from Australia’s deteriorating strategic environment.

Looking at the recent US election, the USSC scholar says that over the decade to 2019 the counties that voted for Joe Biden had population growth that was on average five times that of counties that voted for Donald Trump.

“Nearly 60 per cent of the counties that voted for Trump saw an outright decline in their population over the same period,” he tells Inquirer via email.

“This in turn is reflected in new business formation and employment growth, which occurred overwhelmingly in the counties that voted for Biden. I think the lesson here is that populism is not a response to economic dynamism and internal and external immigration, but its absence.”

Big Australia will be a tough sell while unemployment is high, especially for young people. While the virus is at large, and borders closed, high migration is moot. But economists and business leaders envisage skill shortages emerging even in the early phase of recovery and are urging the government to get ahead of the play.

Gary Banks says it is often difficult to understand what is going on in key areas of immigration that have a big effect over time, such as the temporary and student categories. “When policies are developed behind closed doors, they obviously favour those with political connections who have most at stake. That’s as true of immigration as it was of industry protection,” he says.

“Business groups and the universities naturally want to maximise the intake so as to increase their markets and their revenues. But immigration has wider costs and benefits across the community. These need to be assessed and discussed in an open way before decisions are made.

“The present hiatus provides a unique opportunity to take stock and proceed in a way that would promote greater public trust.

“It’s a fair bet that if immigration gets reset without the pros and cons having had a thorough public airing, government will face a backlash and yet more pressure to retreat.

“There has to be a better way.”

COVID-19 is an asteroid strike on Australia’s rampant population growth and a moment of truth for the nation’s business model.