Dodging the parent trap

The parties are competing to appease migrant resentment over missing parents.

What could be more natural than caring for ageing parents and watching them enjoy the grandkids? BHP employee Hardeep Singh, whose parents from India are visiting him in Perth on a restrictive tourist visa, applied six years ago for a permanent visa for them and he has been told he can’t expect a decision from the government until 2030. His parents are in their 60s. There are almost 100,000 migrant families like his in the queue. Only 7371 permanent parent visas were issued in 2017-18.

In one sense, Singh is lucky in that his only sibling, a sister, lives nearby in the Perth suburb of Queens Park. She has a five-year-old son and her brother hopes to have children soon, so a long visit by their parents would complete the circle. But families with more than half their siblings outside Australia cannot even apply for a permanent parents’ visa.

A month before the July 2016 federal election Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton promised a workaround: an “enhanced visitor visa” to bring in parents of the overseas-born, who in many cases were recruited by Australia Inc as young, skilled workers to help carry the cost of an ageing society.

“The Coalition recognises that many Australians, including our growing South Asian and Chinese communities, face particular pressures through the separation of children from parents and grandchildren from grandparents,” Dutton said. “We want to help families reunite and spend time together, while ensuring that we do so in a way that does not burden Australia’s healthcare system.”

Mixed messages

The story of the mixed messages and confusion that followed offers a glimpse into a big cultural and political shift that has barely registered in the campaign lead-up to Saturday’s vote. Paul Keating once said, “When you change the government, you change the country.” Well-intentioned tweaks to migration policy are less dramatic but can have far-reaching, sometimes unforeseen consequences, for good or for ill, decades later.

Arcane changes in migration rules, loopholes coming to light and policy blunders can transform the intake and set up future interactions with differential birthrates, political or cultural tension at home, and unexpected events of great moment overseas. (Changes in the intake can also open up rich opportunities.) Politicians may sympathise with the very human wishes that come with a migrant-driven country but they are also supposed to safeguard the national interest. Governments have been criticised for bad decisions in the past over lax family reunion programs, and more recently for the international student trade.

Culture shift

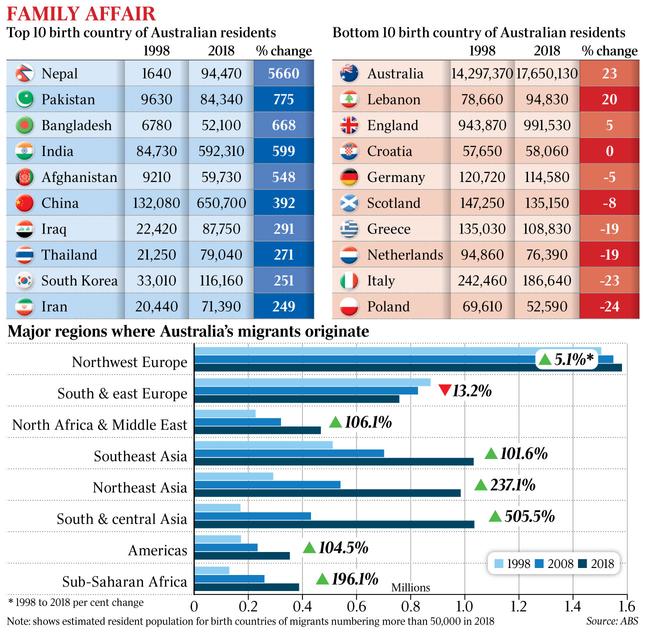

Now the stakes are even higher. The European era in our postwar migration is receding. During the past 20 years, the population of the overseas-born has risen by 70 per cent (compared with 23 per cent for the Australian-born) and there has been rapid growth in migrants from the Indian subcontinent (more than 500 per cent), China (almost 400 per cent) and to a lesser extent the Middle East (almost 300 per cent from Iraq and 250 per cent from Iran).

One of the bigger groups, the Indian-born with a headcount of almost 600,000, made up only 2.4 per cent of total population last year but the trends are significant for the future. Analysis of the political clout of our Indian diaspora has recently begun, and study of the China factor in geopolitics and our democracy has clocked up countless think-tank hours. All this is happening, according to influential London-based political scientist Eric Kaufmann, as anxiety over the pace of ethnic change in the West and resentment at politically correct taboos are pushing conservative whites into the arms of populists, from Donald Trump through the Brexiteers to a host of anti-immigration parties, including Alternative for Germany and One Nation.

Chasing migrant votes

This is the volatile atmosphere in which the Coalition and Labor are competing to appease migrant resentment over missing parents. It’s an issue that shows the overall system in sharp relief, where government has worked for years to redirect the intake to bankable young cogs for the economy after a legacy of problems flowing from family reunion. The prospect of a user-friendly parents’ visa, even a temporary one, is tantalising when all other doors seem shut.

Now, after a three-year wait, the government’s new temporary parents’ visa is here, with a July 1 start date and no restrictive “balance of family” rule. But migrants say it’s not what they expected at all: numbers are capped at 15,000 a year, only one set of parents can be brought in at a time, parents must go home before they can seek approval for a second five-year stay and the fees are high. “The only reason I voted Liberal (in 2016) was because they promised a long-stay visa, and they backflipped on that,” Singh tells The Australian.

Now he and Indians in his circle plan to vote for Bill Shorten because last month Labor offered a better deal: a temporary visa with no limit on numbers, lower fees, valid for both sets of parents who don’t have to leave the country before a five-year renewal.

“I hope Labor does not backflip,” Singh says.

Last Tuesday, Labor’s immigration spokesman Shayne Neumann told the SBS Punjabi service the government had turned its visa “into a money-making venture” while Labor’s version was “very different” and “infinitely better”. “I think the most horrendous, heartless, callous, cruel condition is forcing partners to choose between parents or in-laws,” he said.

Chorus of criticism

Immigration Minister David Coleman says Labor’s uncapped visa is “completely unsustainable” and a “cruel hoax”. He is not alone. Neumann’s policy has united in alarm two leading demographers normally at daggers drawn in the immigration debate: Bob Birrell, who wants a radical cut in population growth; and the University of Melbourne’s Peter McDonald, who shares the view common in government and business circles that our large intake of migrants brings many benefits.

The states have reason to worry, too. The lion’s share of new arrivals goes to Sydney, and the NSW Treasury has made clear its concern that migrant parents needing costly hospital treatment may be unable, or unwilling, to pay. Some Indian migrants tell The Australian they also worry about an unexpected cost to the public purse; they too are taxpayers. Temporary visas do not give access to Medicare, and parents would have to take out private health cover under both the government’s and Labor’s visa, but enforcement may not be easy.

Income, what income?

Having talked up the generosity of its visa at the April 22 policy launch in Sydney, Labor was greeted with a barrage of negative media. Birrell said there could be 200,000 visas in the first term of government, McDonald said there might be 1.5 million to two million offshore parents eligible to come.

Pressed for detail, the party’s campaign headquarters has refused to release any projections of demand but last week stressed how similar its visa was to the government’s “strict conditions”, including a ban on migrant households with less than $83,454.80 in taxable income. The idea is to make sure the local family can pay the costs of the visit. “The income test will reduce the demand somewhat but the pool of eligible parents will still be enormous,” McDonald says. “It is also a bit rich to argue that this is a compassionate policy but restrict it to those with higher incomes. If Labor really wants to be compassionate, it should deal with the 80,000 backlog of partners of Australian citizens waiting for permanent residence.”

The low-key cut to the permanent intake from Labor’s annual target of 190,000 to the government’s 160,000 cap was accepted in an equally low-key fashion by Shorten — “that’s fine”, he said — and this will mean Australians waiting even longer for a partner’s permanent visa. Birrell points to the studied refusal of the major parties to say anything sensible about a key measure of population — “net overseas migration”, in which temporary visas far outnumber the permanent class, and overseas students, especially Chinese and Indians, drive the growth. Many former students now number among migrant families hoping to bring out parents.

As for Labor’s temporary parents’ visa, Birrell says the income threshold would not deter the mostly Chinese 100,000 stalled in the permanent visa queue but would “slow down somewhat” demand from the Indian, west Asian and Middle Eastern migrants locked out of the permanent option because of larger families scattered abroad. “I suspect there would be an initial rush from families who can meet this (income) test — for fear the visa offer may not last long,” he says.

He and McDonald agree Labor’s temporary visa could lead to a de facto permanent intake, with ministers facing heart-rending pleas not to send back aged parents after a 10-year stay, especially if their health has deteriorated. These uncapped visas will grow “inexorably”, according to Brisbane migration agent Peter Kuek-Kong Lee, who lectures in immigration law at Griffith University. He points out that the most pricey variant of the permanent visa has failed in its purpose to curb demand. So the temporary visa would probably generate a rush, he says, citing the “emotionalism” of family reunion, the ever-rising number of overseas-born Australians, and the lack of the restraining “balance of family” rule. And sooner or later wage rises will lift migrant incomes.

Confusion reigns

But the outlook is far from clear for migrant families. They have waited for the government’s new visa, and followed Labor’s parallel commentary on how little the Coalition cares for multicultural Australia. Last week, Neumann was still pushing the line: “(Coleman) has broken his promise to migrant communities.”

In April last year the Coalition put through a regulation that means a single person wanting to sponsor parents on a permanent visa has to have minimum taxable income of $86,606 — up from $45,185. Migrants saw this as sneaky and harsh. Labor promptly put out a statement headed “Tricky Turnbull’s stealth attack on migrant families”, warning of “a real impact on whether or not families are able to be reunited in Australia”. Neumann was one of three opposition spokesmen to put his name to this media release.

Dutton’s 2016 promise of a temporary visa gave migrants some reason to assume that the same $45,185 threshold would apply. April’s regulation was a blow, and this year the government set the income test for the temporary visa at a comparable $83,454.80. Labor has adopted that test without explaining why it’s a fair impost for a single-person household seeking a temporary visa but not for the same household seeking a permanent one.

On Monday night, as Labor showed off its candidates Sam Crosby and Jason Yat-Sen Li at a western Sydney seminar for Chinese-Australians, one woman asked whether an income test applied for the new visa. Crosby said he was “not sure” and Li declared he was “not aware”.

What are voters to conclude? “It’s very confusing for migrant families,” UNSW Social Policy Research Centre senior research fellow Myra Hamilton says. “There’s a lot for them to take in.” After years of stalemate, there has been a “sudden flurry” of policymaking.

She says migrants disappointed by the Coalition’s high fees, cap on numbers and the two-parent limit cannot point to “a firm announcement that these things would not be part of the visa” but other factors may be at play. One reason the government’s offer proved more risk-averse than generous may be that the Productivity Commission has been campaigning for abolition of the permanent parents’ visa altogether — or at least much higher fees. Each of these visas lumbers the taxpayer with a bill for between $335,000 and $410,000 after health, welfare and aged-care costs are counted, the commission warned in September 2016. That same month a government discussion paper on the new temporary visa flagged an income test as well as a bond and raised the issue of health costs.

Meanwhile the Greens want to go the full monty on family reunion, perhaps killing off the “balance of family rule” for permanent visas and spending $12.7bn over 10 years. They would reopen family reunion for asylum-seekers arriving by boat. Would Labor in power come under pressure to adopt the Greens’ policy? Neumann dismisses the minor party, saying they “will never form government” but the emotionally charged nature of the parents’ visa means it’s too soon to predict where politicking may take it.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout