Documentary brings MH370 back on the radar

A Sky News documentary on the 2014 disappearance of the Malaysia Airlines flight makes a strong case for a renewed search.

Six years since Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370 vanished in the biggest aviation mystery in history, new moves are afoot to find out what happened.

The Malaysian government is engaged in tacit negotiations with a British-owned, Houston-based sophisticated underwater search company on whether to launch a new search for the aircraft, and Australia and China also may be involved.

Highly experienced pilots have teamed up with a Brisbane legal expert in a bid to persuade Queensland Attorney-General Yvette D’Ath to launch a coronial inquest into the deaths of the four Queenslanders on board the flight, and D’Ath is prepared to consider the idea.

More evidence points to the Australian Transport Safety Bureau having relied on the wrong theory about MH370 in its $200m failed attempt to find the aircraft.

As the anniversary of the disappearance of MH370 approaches, a new two-part documentary, beginning on Sky News on Wednesday night, contains major revelations about what key players knew about MH370 at the time.

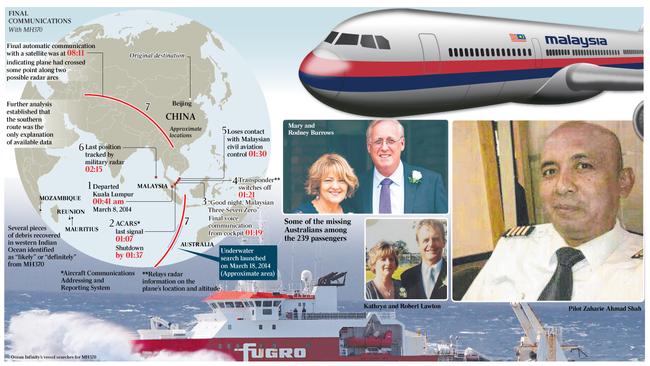

MH370 disappeared on a scheduled flight from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing on March 8, 2014, with 239 people on board.

Forty minutes into the flight and just after the captain, Zaharie Ahmad Shah, signed off from Kuala Lumpur air traffic controllers, saying “Good night, Malaysian Three Seven Zero”, the Boeing 777 vanished from radar screens as its secondary radar transponder was turned off, and radio contact ceased.

A playback of military primary radar showed the aircraft made a sharp turn to fly back over the Thai-Malaysia airspace border, and turned again around Penang to fly up the Strait of Malacca until it went out of radar range.

Analysis of automatic satellite “handshakes” from the aircraft sending performance data from the engines to Malaysia Airlines engineers later found MH370 had turned again on a long track south, and indicated a band on which it was thought to have ended up in the southern Indian Ocean.

A two-year underwater search for MH370 led by the ATSB, working on the theory that no one was flying the plane at the end of the flight and it crashed down unpiloted after running out of fuel on autopilot, failed to find any trace of the aircraft.

Push for new search

Undersea survey company Ocean Infinity, working on a “no cure, no fee” deal with the Malaysian government in which it would receive up to $US70m only if it found the aircraft, mounted its own search in 2018 but also had no luck.

There has been considerable speculation that Ocean Infinity and the Malaysian government might strike another “no cure, no fee” arrangement and launch a new hunt, and a private expert group recently proposed new areas to search.

Signs are that Ocean Infinity has yet to persuade the Malaysians it has enough new material to justify such a venture — but Kuala Lumpur remains open to being persuaded. Last week the Malaysian Transport Ministry said it would need to consult with Australia and China.

“The ministry has not made any decision to relaunch any new searches as there has not been any new credible evidence to initiate such a process,” the ministry said in a statement. “However, the ministry will review any information that it officially receives.”

Ocean Infinity chief executive Oliver Plunkett says “finding MH370 is a topic extremely close to our hearts”, but adds: “The Malaysian government, rightly in our view, set a high bar before they will engage in that discussion.”

Duty to solve mystery

That leaves France as the only country actively trying to find out what happened to MH370.

A secretive French judicial investigation into the loss of the aircraft has been under way for some time, and officials are known to have asked British satellite company Inmarsat to provide the satellite data for independent evaluation.

The French government’s approach is simple: it believes it has a duty to find out who or what killed four of its citizens. Some feel Australian authorities have a similar duty when it comes to the six Australian citizens on MH370.

Brisbane barrister Greg Williams has established that under the Queensland Coroners Act, the state Attorney-General has the power to direct the state Coroner to open an inquest into a death, even if that death occurs overseas.

Williams and two highly experienced former fighter pilots and airline captains, Mike Keane and Byron Bailey, have spent some months communicating with D’Ath’s office to persuade her to launch an inquest into the deaths of the four Queenslanders, married couples Rodney and Mary Burrows, and Robert and Catherine Lawton, who were travelling on a holiday together.

The other Australians on board, Gu Naijun and Li Yuan of Sydney, were on their way to Beijing to be reunited with their young daughters and are not believed to have had any family in Australia.

A recent letter to Bailey from D’Ath’s office says: “So that the Attorney-General can consider this matter, would you kindly provide in writing the new evidence to which you refer”.

Bailey replied to D’Ath: “There is a very strong view in the international aviation industry that the captain of Malaysia Airlines MH370, Zaharie Ahmad Shah, murdered four Queenslanders in a brutal and appalling manner.”

D’Ath would be far more likely to order an inquest if relatives of the Burrows and the Lawtons requested her to do so; The Australian knows some who are considering it. Bailey is correct: most aviation experts say the only credible theory as to what happened to MH370 is that Zaharie, after sending his co-pilot into the passenger cabin on an errand, locked the cockpit door, put on his oxygen mask, which has hours of supply, and depressurised the aircraft, killing all else on board.

The debate is whether after setting the final course south on autopilot Zaharie then took off his own oxygen mask to commit suicide, which is the implication of the ATSB’s “ghost flight” theory; or, as Keane, Bailey and many other aviation experts believe, Zaharie flew it to the end and ditched it.

Analysis by the French government and independent aviation experts of a flap and flaperon found washed up on the other side of the Indian Ocean, including veteran Canadian air crash investigator Larry Vance and more recently a Royal Aeronautical Society expert group, has concluded they were lowered for a controlled ditching.

ATSB spokesmen Paul Sadler and Daniel O’Malley refused to answer questions about MH370, including whether the bureau was sticking to its ghost flight theory. When contacted by telephone, each said: “We’re not engaging with you.”

ATSB Chief Commissioner Greg Hood and other senior ATSB officials have refused repeated Freedom of Information requests from The Australian seeking key material the bureau claims supports its theory, including international expert opinions on the satellite data, saying to do so might cause diplomatic problems.

Keane and Bailey argue that among other benefits of an inquest, it would require serving and former ATSB officers to give evidence in open court about what they know about MH370, and release documents.

-

Mystery flight’s fate inspires elaborate theories

Until MH370 is found and its black boxes recovered, what happened on board the aircraft will remain a mystery.

Ean Higgins’s book The Hunt for MH370 canvasses five dramatised theories that have precedents: a rogue pilot flying the aircraft to the end, a hijack gone wrong, a fire on board, rapid decompression, and the following, presented as an edited extract.

Zaharie Ahmad Shah had enjoyed several mistresses over the years, but none, he found, came close to Rina.

Rina came from a family of fishermen on the coast and she had come into a handsome inheritance.

With Zaharie married, the couple decided to elope.

On the evening of March 7, 2014, Zaharie packed his flight crew bag with some warm clothing, a bright waterproof torch, a referee’s whistle, and his paraglider parachute.

Forty minutes into the flight, having sent his co-pilot Fariq Abdul Hamid back to get him a cup of coffee and locked the cockpit door, Zaharie put on the warm clothing, turned off the secondary radar transponder, put his oxygen mask on which would support him for hours, depressurised the aircraft, and turned the aircraft around.

Zaharie flew the Boeing 777 back over the Malay Peninsula, and turned up the Straits of Malacca. With their 12 minutes of oxygen having run out, the passengers and crew had fallen comatose from hypoxia, or dead.

Zaharie took the plane down to 3000 feet and reduced speed. Seeing the lights of the fishing boat he was expecting, Zaharie made a pass over it, and lined up for a second pass heading south, setting the autopilot towards the southern Indian Ocean.

Zaharie put a deflated life jacket on along with his parachute. He entered the passenger cabin, and opened one of exit doors just behind the wings. He waited until he again saw the lights of the fishing boat approaching, and bailed out.

At the helm of one of her family’s fishing boats, Rina had watched the Boeing 777 pass overhead, kept an eye on the beam from Zaharie’s torch as he descended, and heard the whistle.

Within 15 minutes the love of her life was safely aboard and in her arms, ready to secretly elope to Australia for a new life with stolen passports and the cash from her inheritance safely stowed in the boat.

This scenario has a real-life precedent. In Portland, Oregon, on November 24, 1971, a man calling himself Dan Cooper bought a one-way ticket on Northwest Orient Airlines Flight 305, bound for Seattle, Washington.

Once airborne he showed a flight attendant what was in his briefcase: a collection of wires, switches, and red-coloured sticks. He threatened to blow up the aircraft if he did not get four parachutes and a $US200,000 ransom. When the plane landed in Seattle, the man let the passengers and two flight attendants off the plane, and officials handed over the money in $US20 bills plus the parachutes. Once the aircraft took off again, Cooper told the pilots to “fly to Mexico” — real slow and real low.

At some point thereafter, at night, Cooper lowered the rear stairway of the Boeing 727, and bailed out. He remains missing to this day, despite an extensive manhunt which the FBI only gave up in 2016.

Ean Higgins, a senior journalist on The Australian, is the author of The Hunt for MH370. He spent years investigating the mystery and worked with the Sky News team on the documentary MH370: The Untold Story.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout