Divisive racial debate could derail NZ government

Accusations of white supremacy are flying around as new New Zealand PM Christopher Luxon attempts to unwind some of Jacinda Ardern’s co-governance infrastructure.

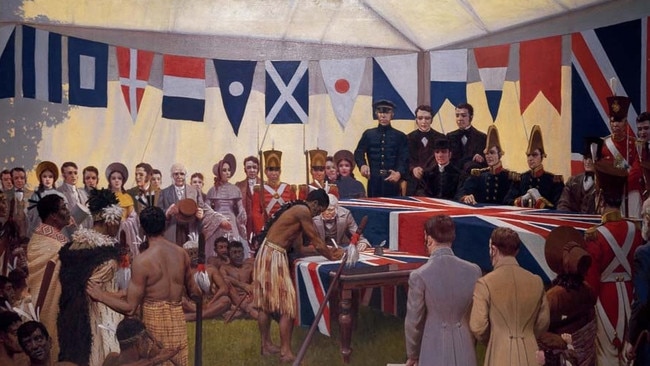

In April 1924, Tahupotiki Wiremu Ratana, founder and leader of New Zealand’s Ratana religio-political movement, travelled to England to present a petition to King George V protesting against Crown breaches of the Treaty of Waitangi. Ratana was prevented from presenting his petition or even meeting the king, but he did succeed in pushing the treaty – NZ’s founding document – to the top of Wellington’s political agenda for years to follow.

A century later the treaty is back at the top of the agenda, creating an ever-deepening divide among New Zealanders amid accusations of white supremacy and wild threats of “war” against the country’s centre-right government.

Last week, at Ratana – the annual ceremony to commemorate Ratana’s birth, attended by politicians from all sides – the Maori King’s spokesman warned Prime Minister Christopher Luxon not to harm the sanctity of the treaty. Rahui Papa promised Luxon Maori would not “sit idly by without a fight” if the text or the meaning of the document were changed.

With the anniversary of the treaty signing just days away, that warning will be resounding among Maori and Pakeha alike.

Two months after becoming Prime Minister on a ticket of unity in a country already divided along race lines, Luxon finds himself teetering on the edge of a precipice.

The National Party was voted into power by a populace disillusioned with the former Labour government. Despite the charisma of former prime minister Jacinda Ardern, New Zealanders had wised up to the fact her government had achieved little for the country, while its pivot to all things Maori – including co-governance with powerful iwi (tribes) and the renaming of government departments in Maori – led to accusations of prejudice against the non-Maori population.

Maori were disillusioned too, arguing that for all Ardern’s promises, outcomes for their people in health, education and life expectancy had not improved under her leadership. Calling the NZ Health Department Te Whatu Ora may have given a nod to their culture but did nothing for their sick.

Almost immediately after Luxon was sworn in, he moved to undo Ardern’s pro-Maori agenda. He switched government department names back to English, with the Maori version secondary; he abolished the controversial Maori Health Authority and he limited use of the Maori language in public departments. While these moves caused upset, the move that has most enraged New Zealand’s indigenous people is Luxon’s decision to partially progress a referendum on the principles of the treaty, which declare a partnership between Crown and Maori.

The referendum was forced on Luxon by ACT leader David Seymour after the October election, as a condition of the libertarian party joining National in a coalition. Both Seymour and National’s other coalition partner, NZ First under leader Winston Peters, had campaigned on a “de-Maorification” platform, with Seymour making a treaty referendum – which was supported by 60 per cent of Kiwis in a pre-election poll – a bottom line of negotiations.

Seymour has no intention of rewriting the original articles of the treaty. It is around the principles – drawn up in the mid-1980s as part of treaty settlements – that he wishes to have a national debate. He argues the principles were never in the original treaty, and have led to discrimination against non-Maori members of the NZ population.

“The idea that the treaty is a partnership between races is wrong,” he tells The Australian. “The principles should be redefined to protect the rights of the non-Maori population. You can be asked to consult on something just because you’re Maori; it means special rights for Maori because they are indigenous. That’s created an enormous amount of division.”

Many on both sides of the divide agree with Seymour that a debate on the treaty would be helpful. The principles themselves were never put out for public discussion when they were first drawn up in 1985 by the Waitangi Tribunal, an organisation made up of academics and members of the judiciary. The tribunal set out the principles in a bid to resolve the differences between the Maori and English versions of the treaty, which had become the source of controversy for decades.

In the English version, Maori ceded “absolutely and without reservation” sovereignty to the Crown, while in the Maori translation, the indigenous people gave the British not sovereignty but “kawanatanga” – the right of governance, while they retained “tino rangatiratanga” – or self determination. The principles went some way towards resolving the disagreements over the issue. However, the principle of partnership between New Zealand’s peoples has led to a number of contentious decisions, including co-governance arrangements which give Maori and non-Maori equal seats around the table in local and national decisions, and which have been introduced with no input from the public.

Luxon agreed on the move towards a referendum only reluctantly – he describes it as “unhelpful and divisive” – and has committed to supporting a referendum only to the select committee stage, meaning it will probably never take place.

Regardless, the coalition agreement itself has become unhelpful and divisive. Maori see it as an attack on their hard-fought-for rights gained under the Waitangi Tribunal – which included millions of dollars in settlements for confiscated land – which they fear will be undone if Seymour has his way.

Opponents have leapt on those fears to accuse the government of white supremacy, with all the underlying connotations of violence this carries.

Shortly after the coalition agreements were announced, the Maori King Tuheitia Pōtatau Te Wherowhero VII called a “hui” – a national assembly – to unify Maori against the government’s agenda.

Maori royalty – like British royalty – stands resolutely outside the political sphere and Kingii Tuheitia’s call, the first in 12 years, was hugely significant.

More than 10,000 Maori, including rival iwi, joined the hui at the royal Turangawaewae Marae two weeks ago, amid fears the meeting could be the beginning of widespread civil unrest.

Some reached back in history to compare the government’s current treatment of Maori with the Land Wars of the mid-19th century, when government troops were sent in to put down Maori tribes resisting English settlers who were stealing their land. The underlying threat was that, as they did 120 years ago, the indigenous people would turn to war to resist government forces.

In the event, Kingii Tuheitia turned the hui into a unifying event after a private meeting with Luxon, and warnings of an uprising began to fade.

But the anger is still there and, as political commentator Chris Trotter says, “I’m not sure Luxon understands the magnitude of what he’s got himself involved in, or whether he has the requisite political skills to navigate himself through it”.

Political analyst Lianne Dalziel, a former Labour minister and mayor of Christchurch, says Luxon is “dancing on a head of a pin” when it comes to National’s intention with the Treaty Principles Bill. “That question will not go away,” she tells Inquirer. “The question I have is did the Prime Minister underestimate the response when he agreed to the ACT and NZ First commitments? And if so, where is he getting his advice?”

It’s likely that Luxon underestimated the deep anger that would meet the principles bill, despite the referendum probably never seeing the light of day. He acknowledges that his understanding of the Maori world is less than it should be and seems not to understand the reverence with which the treaty and its principles are held by Maori.

As commentator Mathew Hooton wrote recently: “Perhaps he looked at it as an outcomes-focused corporate chief executive: sure, the proposal wastes shareholders’ funds, but doesn’t affect the bottom line beyond that, so who cares? “The answer is Maori do, both because the gains since 1990 were so hard-fought and the sheer mana involved.”

Trotter believes the King’s hui did the country an enormous service, reminding all New Zealanders “that Maori are an inescapable part of life in these islands”.

“The Maori King made a very clever, very insightful comment when he said ‘You don’t have to protest, you just have to be Maori’,” he said.

Trotter recalls a story his father told him about troop ships returning to NZ, and Kiwi soldiers weeping when Maori music was played on board. “It was so quintessentially theirs and it said home to them more powerfully than anything else could have done.

“The hui is like that music. It reminds pakeha New Zealanders that Maori are the heart and soul of the country.”

Yet days after Kingii Tuheitia called for unity, Debbie Ngarewa Packer, co-leader of the radical Te Pati Maori, stirred anger up again, telling NZ media the government was showing “all the traits of typical white supremacists”.

Dalziel warns that regardless of what happens with the referendum, damage will have been done, perhaps irreparably.

“The ensuing polarisation will become the story instead of the government seizing the opportunity to resource Maori to deliver effective solutions that our existing systems and practices have not been capable of delivering for generations,” she says.

“It is this that lies at the heart of the challenges we face as a nation in terms of disparities between Maori and non-Maori. And until we recognise this, the promise of national unity will not be fulfilled.”

Ironically, perhaps, the opposite may happen and Luxon will unite the country – although not with him but against the government.

At Turangawaewae Marae, the 10,000 who gathered included bitter rivals among the iwi, some of whom are still fighting border disputes – albeit in the courts. For the first time in years they sat together, putting ancient and modern feuds aside, to voice their anger at the government.

And the anger goes further than the indigenous population. While Dalziel dismisses warnings of civil unrest aside from possibly widespread protests, she points out: “Maori will not be alone. There is a much better understanding across the country about the impacts of colonisation on indigenous peoples.”

Waitangi Day on Tuesday may well light the touch paper under Maori anger. The anniversary celebrations are held in the North Island town of Waitangi, the site of the original treaty signing and, importantly, the heart of Ngapuhi country – the land of NZ’s most radical iwi, who are unashamed of their reputation as hellraisers.

The day has traditionally been a flashpoint for radical elements but under Ardern returned to being a day of unified celebration.

All that may change on Tuesday but if protests go further than, as Trotter says, “giving the Crown a good biff or two” and turn violent, the iwi may well lose the public’s support.

Regardless, Luxon is facing a long battle before he can claim to have united the country in any positive way.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout