Divided states of America: can Biden heal the rifts?

For all the hopes of radical reforms among the woke Democrat rank and file, it’s hard to see the Biden era leaving a lasting legacy.

“We know big government does not have all the answers … a program for every problem. We have worked to give the American people a smaller, less bureaucratic government,” he said in his state of the union address, delivered at the midpoint of an administration that paid down public debt, slashed welfare and toughened up policing.

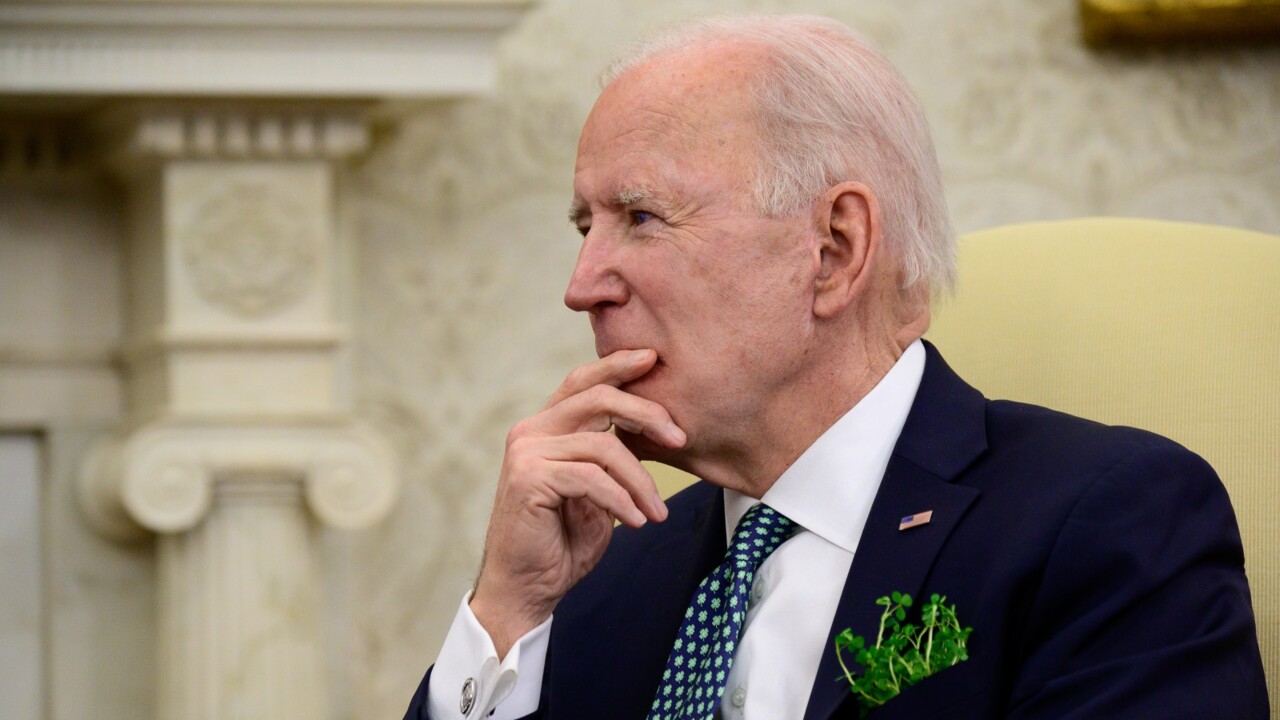

Big government is well and truly back, 25 years later, under his successor Joe Biden. “America is rising anew, choosing hope over fear, truth over lies, and light over darkness,” the new Democrat president said optimistically last month during his first big speech to both houses of congress.

But, for all the spin, it’s hard not to see the reality of a diminished nation: more unequal, more divided, less confident, as it is losing its relative economic and geopolitical clout to China. In foreign policy the new Democrat administration has proved conventional – multilateralist, sprinkled with Obama-era senior officials, and alert and accommodating to Australia’s interests.

But domestically, underpinned by a Democratic Party radically different from Clinton’s, it promises to be the most progressive administration the US has seen, sustained by an intellectual elite increasingly beholden to a “woke” ideology far removed from ordinary Americans’ hopes and aspirations.

Turning Martin Luther King’s desire for a colourblind society on its head, Chicago mayor Lori Lightfoot has announced, for instance, she will no longer give interviews to white journalists.

Fiscally, the new administration is unconstrained by a Republican Party that itself gave up on fiscal rectitude years ago, and is positively emboldened by a Federal Reserve that has been mopping up US government borrowing with new money to the tune of $US80 billion a month for a year.

The defining feature of the Biden presidency is unlikely to be the two mammoth infrastructure bills worth a combined $US4 trillion ($5.1 trillion) that are inching their way through the congress.

These aim to recast the US along more European social-democratic lines: universal childcare, four more years of “free” education, alongside more traditional investments to the nation’s roads, rail and ports.

The bills even include a new federally backed “green” bank charged with financing renewable energy projects that, according to New York University Stern Business School adjunct professor of finance Paul Tice, could end up with a balance sheet of $US1 trillion within a decade.

They inevitably will be watered down in negotiations with Republicans. And if they are passed by an obscure congressional rule, they will be unpicked by future Republican administrations.

Rather, it’s Biden’s climate change policies that will define his presidency. Once Covid-19 fades, attention will focus on the extraordinary costs and changes required to meet the administration’s new goal of slashing carbon dioxide emissions by between 50 and 52 per cent by 2030 (compared with 2005 levels).

In 2019 the US emitted 6.6 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide, about 15 per cent of the world’s emissions or equivalent to half of China’s share. These were 1.7 per cent lower than in 2018, largely as a result of a shift towards gas, solar and wind power instead of coal in electricity generation, and an overall decline in energy use.

The pace of reduction will need to accelerate dramatically. Even if the US could halve emissions from electricity generation, which makes up about a quarter of total US emissions (less than transportation, the biggest contributor), it would still fall substantially short of the President’s promise. Meeting the new target would require removing 2.9 billion tonnes a year of emissions by 2030, which is the equivalent of the combined emissions of all US households, farms and commercial businesses in 2019.

The hundreds of billions of dollars in subsidies to electric car manufacturers and users and to renewable energy projects that are sprinkled throughout the infrastructure bills are all the administration has in the way of a plan.

If it works, and the US looks to be in striking distance of achieving the emissions reduction target by 2024, Biden will be judged a success. If not, it will signal to the world the practical impossibility of meeting global emissions reductions targets.

In any case, the half or so of Americans who say they aren’t willing to spend more than $US10 a month of their own money combating climate change, according to a recent survey by Washington DC think tank the Competitive Enterprise Institute, are in for a shock when the practical effects of the transformation – higher power prices and taxes – become clearer.

The Covid-19 pandemic, which has killed almost 600,000 Americans, has been the defining event of our generation, perhaps the century. It has been a turning point in US history as much as a temporary setback, revealing a new political settlement that shifts the US further away from the 18th-century ideals that underpinned its creation.

Whatever else it achieves, the Biden administration will be remembered for overseeing among the fastest vaccination programs in the world, particularly impressive in a diverse, dispersed population of 330 million.

It’s a myth the US “let the virus rip”; most states and cities implemented strict lengthy lockdowns that wreaked havoc on small businesses and privately employed workers who couldn’t work from home. Most states made masks compulsory indoors and often outside, a practice most have maintained in New York and Washington DC even in the wake of loosened restrictions.

Debates about the effectiveness or justification for all these measures will endure for years in academic and policy circles. But what’s clear already, as Jane Fonda aptly remarked, the pandemic has been “God’s gift to the left”. It is sure to leave a legacy of bigger, nosier, intrusive government, alien to US traditions.

A US Federal court judge, William Stickman, struck down some of Pennsylvania’s lockdown orders in September last year, quaintly arguing “the solution to a national crisis can never be permitted to supersede the commitment to individual liberty that stands as the foundation of the American experiment”.

“In response to every prior pandemic (such as the Spanish flu … when nothing remotely approximating lockdowns were imposed …) states and local governments have been able to employ other tools that did not involve locking down their citizens,” he found.

But his judgment was overturned by a higher court, reflecting the prevailing political reality. Fearful people don’t care about constitutional niceties, they crave action. That action, however popular, may leave more people out of work for longer. Total employment is still eight million less than before the pandemic.

Along with $US1400 cheques for most Americans, in his first major piece of legislation Biden extended Donald Trump’s temporary increase in federal jobless benefits of $US300 a week until September, nearly doubling the average total benefit to about $US620 a week (a far cry from JobSeeker’s new $620 a fortnight payment).

As in Australia, jobs in the US came back quickly once restrictions were eased but, unlike in Australia, the rate of progress has stalled noticeably this year. The unemployment rate even rose to 6.1 per cent last month, a level more than two percentage points greater than the average rate under Trump — the equivalent of an extra 3.2 million people out of work.

Goldman Sachs chief economist Jan Hatzius says the supercharged benefits, which make it more profitable to stay home than work a $US15 an hour minimum wage job, are mainly to blame.

“The median wage is about $US1000 a week, you’d normally get $US500 in jobless benefits but now there’s an extra $US300 a week, so a person on median income gets 80 per cent of their previous wage,” he says. “For about half the unemployed the benefits are greater than what they were earning before.”

The White House says, rather, lingering fears of the virus have dissuaded the unemployed from returning to the workforce.

“But if you look where wages are growing most quickly it’s by far in the lower-paid sectors such as leisure and hospitality. Waiters and kitchen staff,” Hatzius says. The extra cash is due to expire in September, but almost half of the US states, which administer the scheme, have begun to refuse it.

The pandemic has changed the structure of the US economy, too, accelerating earlier trends towards growing concentration within sectors. Banking, airlines, technology and supermarkets are increasingly the preserve of a handful of enormous businesses whose chief executives have become political players themselves.

“We can have democracy in this country or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few but we can’t have both,” early 20th-century Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis famously wrote. If Brandeis was right, democracy in name only is where the US is heading. During the pandemic around 200,000 small businesses, which couldn’t afford to ride out the restrictions, collapsed, driving customers towards bigger established firms.

The US tech giants naturally did best, thriving as more people shopped and worked online, uploading more of their personal data. Facebook’s share price soared 50 per cent during the course of the pandemic. Half a million of Amazon’s 1.3 million global workers joined in the past 12 months. All together, the annual revenue of the big five Silicon Valley giants – Facebook, Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and Apple – raked in about $US1.2 trillion in the pandemic year, up 25 per cent higher than a year earlier.

And don’t let anyone tell you lockdowns were bad for the rich. Between March last year and last month the combined wealth of the US’s 719 billionaires jumped by $US1.6 trillion, or 55 per cent, to $US4.55 trillion, according to Inequality.org. “One-third of US billionaires’ wealth growth over the last 31 years came during the pandemic,” the organisation says.

Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, avowed enemies of oligopolies and inherited wealth, posed a problem for the billionaire class, but Biden, like Hillary Clinton before him, is more reluctant to rock the boat.

Joel Kotkin, California-based author of seven books on class and demographic dynamics and among the most astute observers of the US, foresees a “fresh springtime for oligarchs”. “A golden era of corporate collusion with government seems assured,” he said recently.

Early talk of breaking up the tech giants has fizzled. Earlier this month Biden administration revoked a Trump era executive order that urged the Federal Communications Commission to rethink regulations that shielded tech firms from liability over what they published and distributed – a potentially existential threat. Almost as if returning the favour, Facebook has begun censoring users, even politicians and respected scientists, whose posts question government health policies.

Wall Street banks and Silicon Valley tech giants overwhelmingly supported Biden over Trump, even though Biden had telegraphed plans to lift the corporate tax rate from 21 per cent to 28 per cent.

Similarly, a proposal to put the top federal rate of federal income tax back to Obama-era level of 39.6 per cent will do little to stymie the US trend towards corporatism.

In fact, high earners in high-taxing, typically Democrat states, such as New York and California, could do better under the Biden administration. Some Democrats are pushing to remove a $US10,000 cap on state and local income taxes that Trump introduced.

Biden’s victory has emboldened the social justice movement, whose once fringe ideas about race and gender, far removed from those of most Americans, nevertheless have come to dominate US elite institutions in the media, academy, government and business.

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation gave $US1m to a charity devoted to teaching children that science and maths were perpetuating “white privilege”.

The federal government’s relief program for restaurants affected by the pandemic explicitly discriminated against restaurants owned by white men in favour of minorities.

Coca-Cola and Delta Air Lines criticised Republican states for tightening voter registration rules. Defence giant Lockheed Martin sent its top executive on a course to “deconstruct white male privilege”, it emerged this week.

Nine US, mainly Republican, states, including Michigan and Ohio, have started to legislate explicitly against critical race theory, which teaches that relations between white and black people are permanently underpinned by racism.

Whatever the intellectual merits, the ideas have done little to heal America’s increasingly fractured society. Last year’s surge in violent crime and fatal shootings, at first attributed to fallout from the pandemic and Black Lives Matter protests, has accelerated.

This week, the anniversary of George Floyd’s murder a year ago, there was another shocking mass shooting in which nine people were killed in San Jose, California. So far this year more than 7800 Americans have been shot and killed (excluding 9700 suicides), up 20 per up on the corresponding period last year, and 40 per cent compared with 2019. Calls to de-fund the police are giving way to calls to re-fund them.

The perception the US has become less safe isn’t helped by a humanitarian crisis on the southern border with Mexico, where the well-meaning removal of Trump-era rules has prompted a growing army of arrivals from Central America seeking a better life.

Encounters with US border officials surged to 178,622 last month, up from 78,000 in January. The number of minors in US custody, which the Biden administration has been more reluctant to turn away, has risen steadily from 2400 at the end of November last year to 10,400 at the end of March, according to official figures.

For all the hopes of radical reforms among the woke Democrat rank and file, it’s hard to see the Biden era leaving a lasting legacy.

The Democrats are expected to lose their slender grip on the House of Representatives in the congressional election next year, leaving little time to achieve bipartisan agreement on the infrastructure bills. Their even slimmer one vote hold on the Senate means more radical elements of the Democrat agenda, such as packing the Supreme Court, making Washington DC a state and taking control of running elections off the states, are even more unlikely to succeed.

Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson, with their New Deal, and Great Society reforms, respectively, won office with huge majorities.

Biden is far more popular than Trump at this stage of his presidency, according to the best polls, but much less so than Barack Obama and virtually every other US president since World War II. No wonder; he’s only there because he’s not Trump, whose exasperating and polarising style not only helped radicalise the Democratic Party but caused the Republican Party itself to implode.

Trump has maintained an extraordinary grip on the Republican Party even without a social media presence, and he hasn’t ruled out another tilt for the White House in 2024.

Biden, perhaps even more unlikely given his age, explicitly has said he will run again.

In these circumstances, no candidate from either party can start openly preparing a campaign, making fundraising much more difficult.

Whoever emerges is likely to be someone younger. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and her deputy, Majority Leader Steny Hoyer, are both 81, edging out the President himself, an increasingly frail 78.

Republicans are hopeful a younger – and more appealing – version of Trump emerges, such as Florida Governor Ron DeSantis.

Bill Clinton’s America was younger, fresh from Cold War victory, riding a productivity boom. Biden has inherited a much more difficult set of circumstances: unifying a more polarised, relatively weaker nation at the early stages of a new cold war with China.

In 1996, US president Bill Clinton declared the era of big government was over.