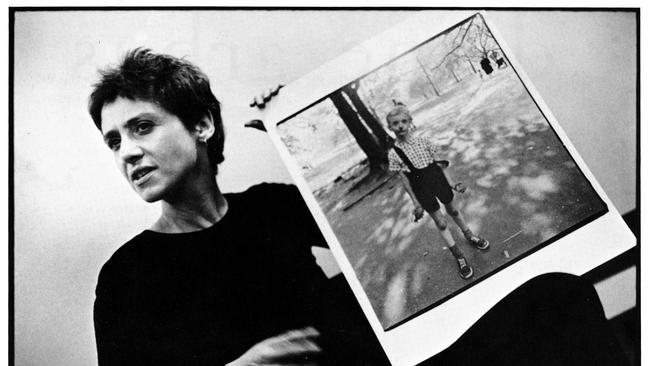

Diane Arbus photographed ignored people leading unnoticed lives — was she wrong?

Ever since photographer Diane Arbus pointed her camera towards society’s misfits, it has been debated whether she should have. Either way, her pictures cannot be unseen | WARNING: Graphic

Predatory or penetrating? The indelible images Diane Arbus took in the closing years of her life have divided students of photography ever since.

When Arbus abandoned her marriage and fashion photography to set up sometimes unnerving portraits of New York City’s most unfashionable, and often odd, people, she shared the same darkroom with her soon-to-be-ex-husband. But the soggy images emerging beneath the orangey safelight on her shifts could be dangerous – and most assuredly could never been unseen.

It is the centenary of her birth next month and so much has happened to photography in the half century since she wrote the words “Last Supper” in her diary before taking an overdose to end her life.

Writing in Time magazine a year later, the Australian critic Robert Hughes – under the headline To Hades with a Lens – spoke of Arbus’s “uniquely truthful scrutiny”. Arbus never avoided the facts of a face. As she pointed out, it was human nature to observe a person’s facial flaws – how different they looked from you. Hughes wrote in November 1972 that her images “had such an influence on other photographers that it is already hard to remember how original it was”.

Nobody denied that influence, but she had vehement critics, including the noted philosopher and activist Susan Sontag who in 1977 published the still acclaimed book On Photography, in which she criticised Arbus and described photographs as “tools of power”.

Sontag controversially insisted that photographs did not convey knowledge; she saw them functioning as “tools of capitalism and colonialism”. Sontag judged them to have the “capabilities of domination and submission analogous to weapons”. And, predictably, she saw Arbus’s work as violating her subjects.

But if it did, it was with their consent. At least for those able to make such a judgment. Arbus famously made friends with those she photographed, dropping by to see them and remembering their birthdays. It is doubtful many others did. These were the souls populating the underbelly of her big city – shunned nobodies who led unnoticed lives. Aliens in the alleys. And they were often unattractive. Some looked dangerous. More than a few were creepy. But to a man and woman, not one is able to be constrained by the simple black frames in which Arbus squared them away. That was the point.

These people lived on her streets. They were as much a part of life as the preferred, left-side portrait of this week’s Broadway star on the glossy covers of Vogue or Harpers Bazaar.

Arbus wanted them seen and heard. Yet surely today she would be cancelled. It is almost certain that delicate petals of today’s unthinking, reflexive left would assume not that Arbus was not turning adversity into art, but that she was exploiting the vulnerable.

Her early photographs created a debate that has never gone away. Are they art? Are they reportage? Should they have been taken? Can the photographer always claim to be just an observer?

Photographs that inflamed this debate include Eddie Adams’s Pulitzer Prize-winning image of South Vietnam police chief Nguyen Ngoc Loan executing a Vietcong prisoner on a Saigon street during the February 1968 Tet offensive. Sontag complained the execution would not have taken place but for Adams being there. Adams wished he never taken it and hoped that when he died the first sentence of his newspaper obituary would not mention that image (it did).

But not shown in that photograph are the victims of the executed man, a cold-hearted killer who murdered South Vietnamese police officers and their wives, children and even parents after kidnapping and binding them. One family had been close to Loan’s, who had cause to believe his family would be next.

Sparking even more intense debate was South African photojournalist Kevin Carter’s 1993 photograph of a vulture stalking a starving Sudanese child trying to reach a United Nations food centre. Carter won a Pulitzer Prize for this the following year. The child (Carter thought it was a girl; it was a boy) survived. Carter did not. He had shooed the vulture away but needed to board a plane moments after chancing upon the image that was on front pages worldwide. Depressed by the furore over it, he took his life weeks after winning his Pulitzer, leaving a note that read in part: “I’m really, really sorry. The pain of life overrides the joy to the point that joy does not exist.” (The boy in that picture, Kong Nyong, died in 2007 of what his father described as “fever”.)

One of America’s most respected photojournalists and filmmakers, Ed Kashi, has travelled the world taking photographs for National Geographic, The New York Times, Newsweek and others. Kashi has taken plenty of difficult photographs of difficult people in difficult situations and believes Arbus would likely encounter hostility and be less appreciated were she working today.

“In hindsight, some of her work could be considered cruel by today’s much less forgiving standards,” he said of the woman he believes worked with “compassion and empathy for the more freakish and vulnerable in our society”.

“Today she could very well be pilloried by certain sectors of the digital lynch mob for ‘taking advantage of’ the less fortunate.” Kashi did not know Arbus, but looking at her work “you can sense she resonated with those outside of mainstream society”.

Bill McAuley, a legendary photographer and picture editor for this newspaper and Melbourne’s major mastheads, agrees. He believes that while all technically trained photographers know how to frame an image, it is the photographer’s heart that knows when to press the shutter.

McAuley has pressed the shutter on some of the most memorable pictures to appear in Australian newspapers, including two ageing virginal brothers who lived in an isolated cabin in the Dargo High Plains built from oil cans and stringybark by their father a century before. And unforgettably, McAuley photographed a distressed pensioner, Robert Swain, bashed in a park for his fortnightly income.

Arbus would have been drawn to both and McAuley concedes they were vulnerable.

“I think an artist, whether they are aware of it or not, is subconsciously making order from chaos,” he said. “They are addressing their own psychological needs with the pursuit of their art.”

Arbus, he says, was driven by her own experiences, her own needs, to make order from her chaos. “You might think she has a resonance with her subjects, or she wants to find out more about them, but to me it’s really just finding out about yourself. That goes for writers, artists, sculptors, painters, musicians …”

Notwithstanding that many of Arbus’s photographs are posed – the contact sheets of rejected images confirm that they were sometimes posed over and again – McAuley describes them as “realism” and believes she was fearless in taking them “and not backing down and not blinking – photographing them honestly”. Hers “is an important body of work because it reflects an era”.

She was born Diana Nemerov in New York City on March 14, 1923, to a hardworking Russian Jewish family that had prospered and ran a Fifth Avenue department store. It was a life vacant of loving parents whose proxies were nannies and maids. Detached from a need to find work she turned to art, as did her sister, who became a sculptor. Their older brother, Howard, became US Poet Laureate.

Since an early age her boyfriend had been Allan Arbus, who worked at her parents’ store and became a photographer whom she married at 18 and bore two daughters. One became a novelist, the other followed in her parents’ footsteps and her many portraits for Rolling Stone, Vanity Fair and The New Yorker are highly acclaimed.

The Arbuses built a studio and a commercial photographic business and remained friends after separating in 1959. Allan always wanted to go to Hollywood to act and did so in 1969, appearing in a few films, and starring as the psychologist Major Sidney Freedman in the long running M.A.S.H. television series.

Always supportive of his former wife, Allan once told a reporter: “She got herself to go up to people on the street and ask if she could photograph them. One thing she often said was, ‘I’m just practising’.”

In 1967, she spotted New Jersey twin girls dressed similarly, but not identically (although this would take the viewer a time to notice) and her black and white image of the seven-year-olds is one of the most famous of the century. Arbus called it “differentness in identicalness”, and she was right about us all seeking differences in faces; it hard to stop looking at them and slowly noting their ever-so-slight apartness.

Perhaps her second most famous images were of the blighted young Israeli man, Eddie Carmel, whose growth hormone disorder caused gigantism. When Arbus met him in 1970 – a year short of her own death and just two from his – he was reportedly 2.74m tall and in her photographs he bends over to fit in his parents’ Bronx apartment. He was known as The Jewish Giant and spent most his life involved in circuses and gimmicks. A print from this series sold five years ago for almost $1m.

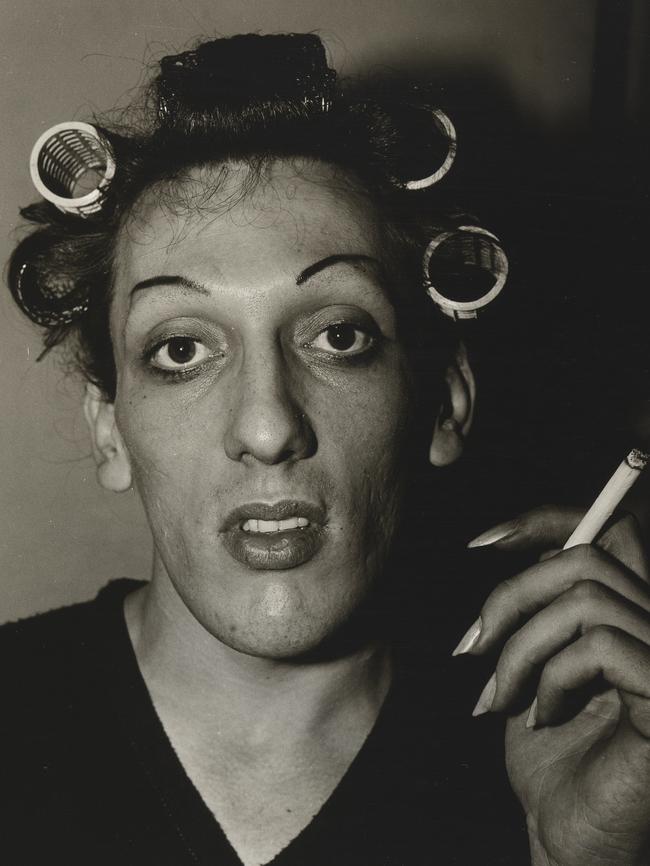

Another series was of a day in the life of a transvestite, from doing his hair, to dressing up as a woman at home, walking through the city and returning to his flat.

Days before Arbus died she photographed Germaine Greer at the infamous Chelsea Hotel following the publication of Greer’s The Female Eunuch. Greer disliked the encounter and felt manipulated: “Pinned on the bed by her small body with the big camera in my face, I felt my claustrophobia kick in; my heart-rate accelerated and I began to wheeze. I understood that as soon as I exhibited any signs of distress, she would have her picture.”

The Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Norman Mailer said of the photographer that “Giving a camera to Diane Arbus is like giving a hand grenade to a baby’’.

Arbus said of her photographs: “They are proof that something was there and no longer is. Like a stain. And the stillness of them is boggling. You can turn away, but when you come back they’ll still be there looking at you.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout