D.H Lawrence’s epic Australian adventure to unravel our mysteries

It’s a hundred years since the author’s 100 days in Australia but it resulted in the masterpiece novel Kangaroo.

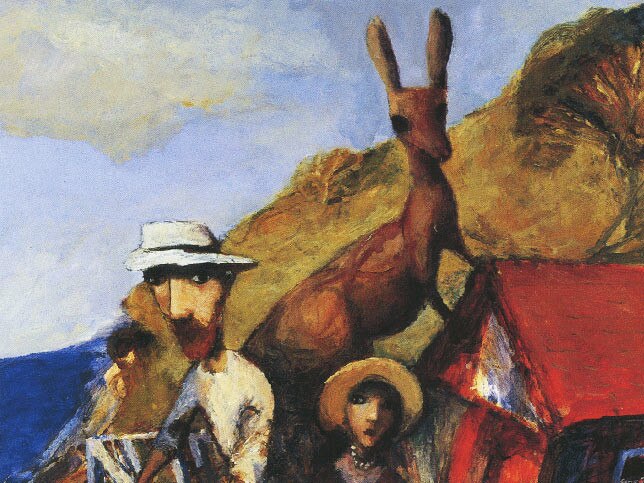

Sunday, July 30, 1922: well-dressed travellers stop for a pictorial memento of their picnic at a local beauty spot, Loddon Falls. The enthusiastic amateur photographer, Denis Forrester, a hosiery mechanic, has incorporated his wife Laura, work colleague William Marchbanks and his wife Constance. Still, the eye alights most readily on the central bearded figure.

D. H. Lawrence, often rather saturnine in photographs, looks almost relaxed, perhaps because he has just posted to his American agent a bundle of exercise books containing what had consumed him for the seven preceding weeks: the handwritten manuscript for Kangaroo, described (by Simon Leys) as “the most truthful and disturbing image one can find of Australia in literature”.

Wednesday marks a hundred years since Lawrence and his wife Freida arrived in Fremantle for a hundred-day Australian stopover, having departed Italy en route to their planned destination of New Mexico, with its glimmer of the long-sought utopia he dubbed Rananim.

Has any creative commuter filled their time so gainfully? During two weeks in the hills west of Perth, 36-year-old Lawrence inspired the proprietor of his guesthouse, Mollie Skinner, to write a baggy manuscript, which he would rework into a gritty coming of age novel, The Boy in the Bush (1924).

Skinner was fascinated by this frail, tubercular figure – “hardly a man, but a spirit, unfinished, like music”. To her he imparted some timeless writer’s advice: “Use the form of a diary … write in little sections, in just those little flashes of scenes and incidents following one another in haphazard event, brief, poignant, telling.”

It was in this vein Lawrence set about composing Kangaroo, an episodic modernist mood piece synthesising memoir, thriller, travelogue, and philosophy, scribbled at an average of 3500 words a day. He became, as Nicolas Rothwell says in the most recent edition, “the first modern writer of world stature to lay eyes on Australia and spend himself upon its mysteries”.

The novel was a revelation to Patrick White, inspired artworks by Sidney Nolan, Garry Shead and Brett Whiteley, was adapted for the screen by Tim Burtsall. Scattering citations from Kangaroo throughout the final volume of his History of Australia, Manning Clark declared himself “overwhelmed by the genius” of Lawrence and, like many other readers, wondered “how did he find out so much about us [Australians]”.

Lawrence initially had no such intentions. “I don’t know what we’ll do in Australia – don’t care,” he wrote on the way to Perth.

Yet the southern continent had loomed in his imagination even before his abandonment of England in November 1919, disillusioned with the creeping advance of industrial ugliness, excesses of wartime bellicosity and the rule, as he saw it, of the mob.

Lawrence disposed of a character in the Australian bush in his first novel, The White Peacock (1911); he paraded a doctor with an Indigenous tinge in The Lost Girl (1920) and a gay Australian aesthete in Aaron’s Rod (1922).

His curiosity was further pricked when, en route from Naples, the Lawrences encountered Anna Jenkins, a vivacious Perth widow reading Sons and Lovers.

Lawrence quizzed Jenkins about all aspects of Australian life. She in return prepared the author a warm, even effusive, welcome – so excited by an impending meeting with Lawrence was the novelist Katharine Susannah Prichard that she went into labour and bore her second child.

Lawrence was immediately captivated by Australia’s landscape: the sky “high and blue and new, as if nobody had taken a breath from it”; the bush “so phantom-like, so ghostly … biding its time with a terrible ageless watchfulness, waiting for a far-off end, watching the myriad intruding white men”.

How lightly white Australians lived, on the surface of this great ancientness, surrounded by “the invisible beauty of Australia which is undeniably there, but which seems to lurk just beyond the range of our white vision”.

How lightly Lawrence lived also. He made connections with disarming readiness: coming east aboard the P&O steamer Malwa, for example, he fell in cheerfully with the Forresters and the Marchbanks.

But, having docked at Circular Quay at dawn on May 27, Lawrence cleared out of “crude, raw and self-satisfied” Sydney after a couple of days.

These images are among a small cache in the Newcastle Public Library, now supplemented by a full set of the photographs held by Forrester’s granddaughter and lovingly gathered by retired academic Christopher Pollnitz, providing the only visual evidence of his stay.

The press ignored him, more excited by a simultaneous English literary visitor, Agatha Christie, a member of the British Empire Exhibition Mission.

Instead, the Lawrences gravitated to Thirroul, which better suited their finances: the couple had less than £50 between them while awaiting the arrival of a bank draft from his agent.

The Marchbanks helped fund their rental of a cosy bungalow, with sea views and an open fire, named “Wyewurk” – ironic given Lawrence’s furious industry at its jarrah table, which commenced two days after his arrival.

Scholars have tracked Kangaroo’s evolution closely, identifying Lawrence’s lurches of creativity by reference to his copious correspondence, in which he rehearsed parallel impressions and themes.

Lawrence and his fictional alter ego Richard Lovatt Somers feel at times interchangeable; passages in Kangaroo and Lawrence’s letters could be transposed without difficulty.

“This is the most democratic place I have ever been in,” Lawrence complained to his sister-in-law on June 13.

“And the more I see of democracy the more I dislike it. It just brings everything down to the mere vulgar love of wages and prices, electric light and water closets, and nothing else.”

“Oh how I detest this treacly democratic Australia,” Somers laments in Kangaroo. “Before one knows where one is, one is caught like a fly on a flypaper.”

Real places are only slightly veiled; real people have been mined for names and characteristics. Harriett Somers stands in for Freida Lawrence. The Somers’ first Australian neighbours are the Callcotts – the name of the estate agent who managed Wyewurk.

Jack Callcott is integral to such plot as Kangaroo contains. Enigmatic and conspiratorial, he draws Somers into conversation about politics, thinking to involve the Englishman in a proto-fascist movement of disillusioned ex-Diggers bulking darkly out of sight.

“Australian soil is waiting to be watered with blood,” claims Jack. “What we want in Australia isn’t a statesman, not yet. It’s a set of chaps with some guts in them, who’ll obey orders when they find a man who’ll give them orders.”

When Somers does not flinch, Callcott is excited: “I knew that we was mates … This is fate and we’ll follow it up.”

Callcott duly introduces Somers to the eponymous Kangaroo: Benjamin Cooley, a charismatic ex-soldier turned barrister. Cooley believes that man “needs to be relieved from this terrible responsibility of governing himself when he doesn’t know what he wants” by a “quiet, gentle father”.

Somers is captivated as further details emerge of their sprawling, cellular paramilitary organisation.

Then, via another character, the pragmatic Cornishman Jaz Trewhella, Somers meets trade union boss Willie Struthers, who presents his own vision: a land built by organised labour, a “grand, solid, working-class people”, united by a “love of mates”.

Struthers seeks to interest Somers in the editorship of “a true People’s paper”, which would “breathe the breath of life into us, through the printed word”.

Somers is stirred by Struthers too (“He’s a force, he’s something”); he, like Lawrence, feels a residual kinship with the working classes. But the tendency of politics, Somers cavils, is to “make money the only god”, which is a “treacherous conspiracy against the generous heart of the people”.

As he recoils from the tug of both alternatives to bourgeois democracy, Kangaroo’s hold over him weakens.

“You are not with me,” Kangaroo intuits when next they meet. They part coldly, with Kangaroo warning: “I could have you killed.”

Callcott leers: “You’ve found out all you wanted to know, I suppose? … Exactly like a spy in my opinion.”

Confrontation now feels as “inevitable as the coming of summer”. In the penultimate chapter, the rival mobs are incited to frenzy. Callcott kills, nonchalantly (“Nothing bucks you up sometimes like killing a man”). Kangaroo perishes, madly (“We’ve got to save the People, we’ve got to do it!”).

For decades after publication, readers looked askance at the novel, unable to reconcile Kangaroo with acknowledged currents of Australian history.

The Australian poet A.D. Hope denounced it as the “entirely factitious”; the English critic Richard Aldington sniffed that “at the time no such political violence occurred in Australia”. Lawrence was assumed to have been inspired by encounters with Italy’s incipient fascism, which culminated in Mussolini’s march on Rome in October 1922.

Around the mid-1960s, however, perspectives changed. Writing in Meanjin, Rev John Alexander argued for a rethink, that Lawrence was “closer to the facts than almost all critics have to date recognised”.

In Kangaroo’s mysterious movement, Alexander saw counterparts of the returned soldiers’ clubs and masonic lodges then flourishing in Australia, and antecedents of the New Guard; in Struthers he discerned A.C. Willis, influential president of the Miners’ Union.

Kangaroo, he observed, deserved to be considered “a serious study of some of the deepest questions vexing Australia’s political life both in 1922 and today”.

This reappraisal climaxed in D. H. Lawrence in Australia (1981), in which journalist Robert Darroch traversed conjectures that Kangaroo was essentially a transcription of events powered by actual encounters.

He identified Kangaroo as Maj-Gen Charles Rosenthal and Callcott as Major William James Rendal Scott, leading lights in a patriotic coalition, the King and Empire Alliance, concerned by Australia’s halving of its military spending in 1922-23.

Rosenthal, a decorated veteran wounded five times in World War I, was a sharp critic of the abandonment of compulsory military training. Lawrence, Darroch claimed, had become aware of Rosenthal’s sedition and been warned to move on.

The case is intriguing, if short on specific evidence. Still, theories have flourished since, ranging from that Kangaroo’s Victorian counterpart “Emu” (“a smart chap, a mining expert … [who] would be the Trotsky to the new Lenin”) is Rosenthal’s friend Sir John Monash, to that Somers’ sense of being watched was well-founded because of Scott’s association with intelligence services (“Perhaps the secret service was making investigations into them”).

Yet it is possible to read Lawrence’s book knowing nothing of 1922. The themes update easily, for secretive and paranoid caballing never goes out of fashion: these days Cooley and Callcott would share with Somers their findings about 5G and George Soros.

Somers/Lawrence demonstrates acute insight into Australian obedience (“No control and no opposition to control … Every man his own policeman”), austere work-centeredness (“Nothing but the absolute drive of the world’s work kept them going”) and egalitarian material-mindedness (“There was a difference of money and of ‘smartness’. But nobody felt better than anybody else, or higher; only better off”).

White settlement, still so recent, is depicted as discouragingly derivative and diffuse: “In the openness and the freedom this new chaos, this litter of bungalows and tin cans scattered for miles and miles, this Englishness all crumbled out into formlessness and chaos.”

“Even the heart of Sydney itself – an imitation London and New York, without any core or pith of meaning. Business going on full speed: but only because it is the other end of English and American business.”

These shallow roots leave it vulnerable: “Can a great continent breed a people of this magic harmlessness, without becoming a sacrifice of some other, external power?”

More lately, scholars have also looked at Kangaroo’s subtle evocations of Indigenous absence, addressed indirectly and obliquely, as in the chapter “Bits”, which rummages in the old Bulletin column “Aboriginalities”, of which Lawrence was an avid reader.

David Game of Australian National University has identified the tension in Kangaroo between the spirit of the landscape (“this land always gives me the feeling that it … doesn’t want men to get hold of it”) and the tenuousness of white settlement (“sprinkled on the surface of darkness into which it never penetrated”), with glances at the apparent erasure of the intermediating culture (“It seemed to Somers as if the people of Australia ought to be dusky”).

As Game observes in D. H. Lawrence’s Australia (2015): “The amorphous aboriginal spirit is unsettling, as if Aborigines have only recently or temporarily decamped the settler occupied land – as when one enters a room presumed to be empty and is surprised to find a teapot still warm on a table.”

There is, all the same, an underlying goodwill. Around the time of the picnic, Lawrence told a correspondent: “In truth I sit easier here than anywhere.” Freida recalled in her autobiography that she “would have liked to stay in Australia and lose myself”.

“I like it,” says Harriett Somers as the couple contemplate departure. “It doesn’t feel finished.”

Her husband laughs: “Not even begun.”

View Newcastle Libraries photographic collection of D.H Lawrence’s stay in Thirroul.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout