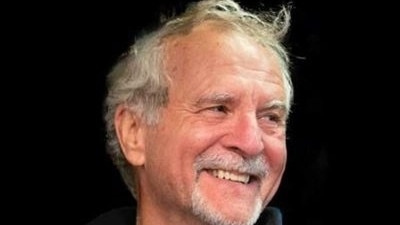

Deep-sea explorer Paul-Henri Nargeolet knew the dangers of diving on the Titanic

Deep-sea explorer Paul-Henri Nargeolet was a hero in France, but others were less impressed that he collected artefacts from the Titanic.

The 2240 passengers and crew who set sail from Southampton on April 10, 1912, aboard the 270m-long Titanic knew they had boarded the world’s largest moving man-made object, boasting unique safety features, including the electrically controlled watertight doors on the bulkhead compartments.

Theirs wasn’t just a show of faith in the White Star Line, whose managing director was on board, as was the builder, but in the modern technology adapted for the Titanic that notoriously led to a reporter on The Irish News and Belfast Morning News on June 1, 1911, to report it as “unsinkable”.

Of course, technology on the Titanic – including the bulkhead design – failed spectacularly and 1500 died.

Paul-Henri Nargeolet spent his life putting faith in technology. He lived in Morocco for a time as a child and first dived off its coast, becoming hooked on the underwater world. He joined the French navy, where he spent decades in a series of roles including diving to clear mines and search for lost aircraft and boats. Indeed, he was on such a clearing mission along the Suez when the call came from Ifremer, a French government-owned oceanographic research organisation. It scours the ocean floor seeking answers to questions such as whether life on Earth might have started in one of the oceans’ deep hydrothermal vents.

In 1956, at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, a private higher education and research college in Massachusetts, a group of scientists promoted the idea of manned deep-sea submersibles to study and better understand the oceans about us.

In the mid-1960s, they built an unmanned submersible called Alvin and dived off the Bahamas to various depths. In January 1966, a US B52 bomber collided with a refuelling tanker over Spain. Three of its hydrogen bombs hit land, but one was lost in the Mediterranean.

Alvin found it and the bomb was recovered, proving the submersible’s invaluable worth.

It was on a manned research trip aboard Alvin in 1977 – the French-American team included geologist diver Robert Ballard – that they found the first deep-sea vent 150km west of the Galapagos Islands. Eight years later, Ballard was aboard the Woods Hole craft RV Knorr on a secret US Navy mission using sonar scanning technology to photograph the remains of two lost nuclear-powered subs. In return, the navy allowed its former mariner to use the technology to search for the Titanic, which he found on September 1, 1985. The following year, Ballard returned on Alvin and after endless technical hitches and at a depth 200m above the seabed they spotted her 3800m deep: “Directly in front of us was an apparently endless slab of black steel rising out of the bottom – the massive hull of the Titanic.”

The following year, an Ifremer-sponsored dive aboard the submersible Nautile, with Nargeolet aboard, headed down to survey the Titanic in detail and to retrieve items scattered around, but not within, the shipwreck.

It is reported they recovered 1800 artefacts, and thousands more in subsequent dives. But as plates, binoculars, a child’s marbles and passengers’ boots were recovered, some survivors and relatives of those lost that night were less than happy.

Eva Hart was 82 when Nargeolet’s salvages began. She had been seven and on board when the Titanic hit the iceberg. Her father Benjamin wrapped a blanket around his little girl and propped her beside his wife Esther in a lifeboat. “Be a good girl and hold mummy’s hand,” she recalled being his final words. In 1987, she told London’s The Times newspaper that “to bring up those things from a mass sea grave … shows a dreadful insensitivity and greed”.

Overcoming her dreadful experience, Eva sailed to Australia 15 years later and reportedly was a semi-professional singer.

Among the varied accounts of Titanic’s final moments, Eva insisted the ship had broken in two, which Ballard confirmed in 1985.

Later research indicated that the stern rotated as it sank, which may account for the kilometres-wide debris field.

Nargeolet would complete 37 dives on the site and was on his 38th aboard the Titan submersible when it headed towards the seabed last week before imploding due to an unknown catastrophic failure.

Four years ago he told a reporter from the Irish Examiner: “If you are 11m or 11km down, if something bad happens, the results are the same.”

He’d been due to open another Titanic exhibition in Paris this month. Nargeolet’s daughter Sidonie said whatever the outcome of the investigation into Titan: “In any case, he is happy where he is. And that is reassuring.”

Paul-Henri Nargeolet Deep-sea explorer and Titanic expert.

Born Chamonix, France, March 2, 1946; died in the North Atlantic, June 18, aged 77.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout