Deep dive to new resources

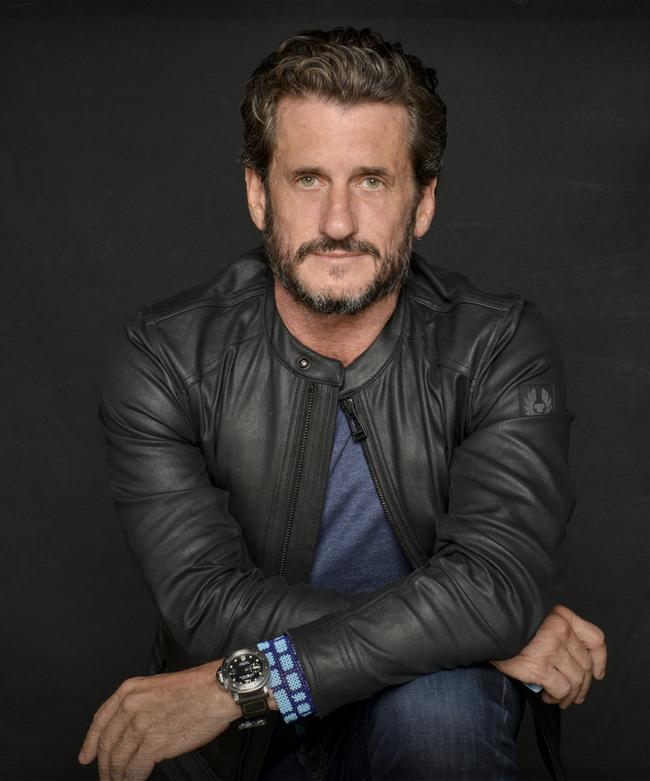

Gerard Barron wants to secure a battery-powered future — from the sea floor.

Where Musk is obsessed with electric cars and deep space, Barron is focused on the abyssal plains located 4500m below the surface of the Pacific Ocean.

Barron is leading a gathering push to exploit a base metals resource that has been known about a long time but has been too difficult to exploit for political, environmental and logistic reasons.

It is as if nature has assembled the ingredients needed to make batteries — manganese, nickel, cobalt and copper — rolled them into marbles and scattered them across the ocean floor.

Enough polymetallic nodules have been identified in the Pacific Ocean’s Clarion-Clipperton Zone, located between Hawaii and Mexico, to secure the world’s battery-powered future two times over. According to published data, if half of these nodules were collected, the total commercial value would be about $US5 trillion.

Barron says his company, DeepGreen Metals, is at the forefront of a global rush in international waters including sovereign programs from China, Britain, Singapore, South Korea, Japan, France and Germany.

He says the base metal nodules can be harvested from the ocean floor with minimal disturbance by robots, with vision from the mine site made available to regulators and the public in real time. Because of the high grades and combination of metals, production costs are estimated to be in the bottom quarter of land-based mines.

Deep-sea mining is being touted as the missing piece of a complex puzzle that answers a question too few people in the environment movement have been prepared to ask — where do the resources come from for the great green revolution without trashing the world?

Moving the world from its reliance on coal, gas and oil to renewable energy will require a massive increase in production of metals used in batteries, some of which are scarce or available only in a few countries. China has a near monopoly on rare earths needed for hi-tech manufacturing. Cobalt comes predominantly from child slave labour in the Congo in Africa.

If wind, solar and batteries are the future of the world, too few people are asking: where is all the nickel needed to make them going to come from? Nickel mining can be environmentally destructive, particularly as many new deposits are found in heavily forested areas of Asia and South America. Carmakers are desperate for nickel and the 20 other minerals needed to make batteries to feed the transition to electric vehicles.

Some are offering big contracts for environmentally friendly supplies to the world’s top nickel producers of Indonesia, The Philippines, Russia, New Caledonia, Australia, Canada and China. The experience is that if environmentally friendly nickel does exist it is not available at current world prices of $US15,807 a tonne. Even a small change in the price of nickel can have a big impact on the end price of an electric-powered car.

DeepGreen says it can produce the metals needed for the renewable power and transport revolution at prices equal to the lowest cost traditional land-based mines.

But first, Barron must overcome the environmental sceptics who say DeepGreen is just another greenwash venture in the post-fossil fuel industrial revolution.

In a Zoom conference from California, Barron comes across like a quintessential digital era entrepreneur: long hair, T-shirt and bangles, and an oft-repeated desire to leave a better world for his children.

But Barron has deep Australian roots. He grew up on a dairy farm at Biddeston near Oakey on the Darling Downs in Queensland and started his first company while at the University of Southern Queensland.

He has built several global companies in battery manufacturing, publishing, telecoms and software. The 54-year-old was the founder and former chief executive of advertising management and distribution network Adstream, which he started in Sydney in 2000.

Barron became involved in deep-sea resources in 2001 through a geologist friend, and after learning about sea-floor polymetallic nodules he backed a new venture in 2011. He stepped into the role of DeepGreen’s chairman and chief executive in 2017 to refocus the company on the environment.

Barron says he still has a family bolthole at Peregian Beach on the Sunshine Coast “to keep us sane when we are longing for Australia”.

His vision is to close the loop on metals with recycling to eventually end the need for new mines. But first enough new material must be put into the system without exhausting the world.

As the shift to renewable energy and batteries gathers pace, attitudes to the company have started to change.

“Until recently we had raised $US150m and it felt like we had raised them $1 at a time,” Barron says. “It has suddenly dawned on people we have an existential crisis raining down on us and we have to find a new supply of this stuff.”

DeepGreen’s thesis is borne out by the research.

A paper published last month in Nature Communications says increased mining activity needed to power the world’s transition to renewable energy may pose a bigger threat to biodiversity than the climate change it is trying to solve. It says there is an urgent need to understand the size of mining risks to biodiversity but “none of these potential trade-offs are seriously considered in international climate policies”.

A white paper analysis sponsored by DeepGreen found that producing metals for the green transition the way we have been producing them so far will shift the environmental and social burden from fossil fuels to metals. It says life cycle assessment shows the climate change benefits of transitioning to greener cars will be partially undermined by producing the metals needed for the transition.

“We hope our work helps frame the conversation and the difficult choices ahead for society to source metals for the green transition responsibly, ethically and with minimal extra emissions load on the planet,” the research says.

Research supported by DeepGreen and published in the Journal of Cleaner Production says if the green transition is to proceed, a large new injection of primary metals extracted from the planet seems unavoidable.

“Yet nickel and cobalt mined from land ores face great challenges in meeting this new demand, with too few projects in the development pipelines,” it says.

Despite its ethical pitch, deep-sea mining faces strong opposition from many within the environment movement.

Many are wary of sea mining following the disastrous experience of Nautilus Mining, which collapsed amid claims of environmental devastation. The target resource and methods being used by DeepGreen are vastly different to Nautilus, which Barron says “has done us no favours”.

But environment groups are unconvinced. “Reckless deep-sea mining companies are keen to start plundering the seabed for minerals and metals, risking irreversible wildlife loss and disturbing important carbon stores that could make climate change worse,” says Greenpeace senior political strategist Louisa Casson.

The Pew Foundation says nodules take more than one million years to form and cannot be replaced in any meaningful way.

“Scientists are just beginning to study some of the array of species that live at these depths, from sponges and sea anemones to shrimps and octopods,” Pew says.

“Little is known about how far they range, how populations are connected, and what damage may be caused by the spread of sediment plumes and other effects of mining.”

A literature review led by James Cook University academics Andrew Chin and Katelyn Hari found “the accumulated scientific evidence indicates that the impacts of nodule mining in the Pacific Ocean would be extensive, severe and last for generations, causing essentially “irreversible damage”.

In response, Saleem H. Ali from University of Delaware says ultimately the environmental impacts will need to be considered as a comparative life cycle assessment between terrestrial and oceanic minerals.

“Oceanic minerals development needs to be considered as part of a socio-ecological conversation about planetary sustainability at supply and demand nodes,” Ali says.

“The environmental movement should learn some of the lessons of its absolutist opposition to nuclear power, which led to industrial research stagnation and a lost opportunity for climate mitigation because of extreme risk aversion.”

Barron says he has been disappointed with the attitude of environment groups. “They just say we should not be supporting any more extractive industries and we should just find ways of consuming less and recycling,” he says.

The problem, says Barron, is the transition to electric vehicles alone will require volumes of metals that have not yet been produced to recycle. In addition, developing nations will rely on new materials to progress to First World standards of living.

As a result, Barron is investing heavily in research of the ocean resource and he wants the science to tell the story.

In November, a group of 50 scientists and crew left as part of a $US60m ($78.9m) ocean research program to begin baseline studies that will inform DeepGreen’s environmental impact assessment.

Located off the coast of Mexico, the sub-sea area is the resting place of nickel and copper deposits that over geological time have weathered from the Andes and Rocky Mountains of the Americas.

Much like a pearl grows, the base metals have formed into nodules around a grain of sand or broken shell or shark’s tooth. Manganese provides a bonding agent to trap the metals that have precipitated out of the ocean floor.

“This is like golf balls lying on a driving range,” Barron says.

“We are not talking about having to dig, tunnel and blast. From our perspective these nodules lie unattached. We can use fabulous innovation that allows us to lift the nodules while barely touching the surface.

“We can design to minimise the impact but of course there will be impacts. The question is what are they and how do they compare to the known impacts of what we do today.”

The size of the resource is enormous.

“We are talking about a confirmed area of one million square kilometres under licence, and we have about 225,000sq km of that, and on that one million square kilometres there is enough nickel and copper and cobalt to electrify the entire passenger transport fleet two times over,” Barron says.

Because the resource is located in international waters it is administered by the International Seabed Authority.

As part of the agreement to develop mining operations, the company has entered royalty agreements with Pacific Island nations Tonga, Nauru and Kiribati.

“We hold the contract with the International Seabed Authority and then have a sponsorship agreement with the developing nations,” Barron says.

DeepGreen aims to be in production by 2024. To get there it must work to build the social licence that will enable big consumer-facing brands to participate.

“From an environmental perspective you have to have thick skin,” Barron says.

In the global race to remake the world for a low emissions future, Gerard Barron just may be Australia’s Elon Musk.