Crunching the numbers on Australia’s STEM decline

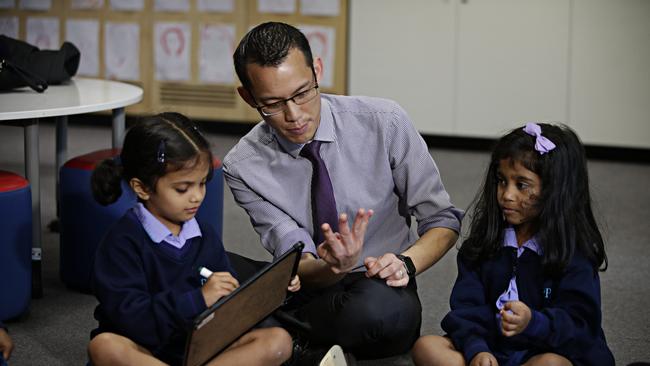

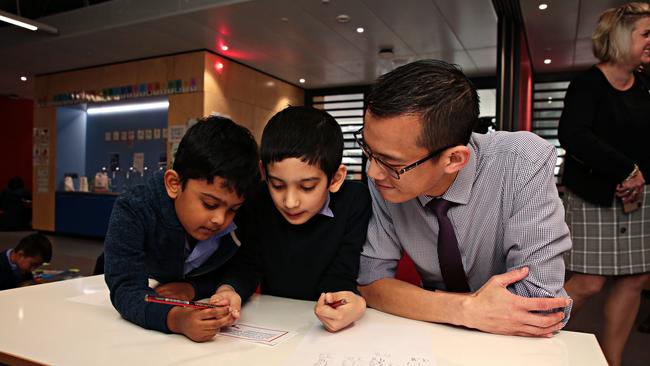

Eddie Woo, Australia’s most celebrated teacher of mathematics, has a solution for the teenage brain drain.

Eddie Woo, Australia’s most celebrated teacher of mathematics, has a solution for the teenage brain drain. With four in 10 maths teachers not qualified to teach the crucial subject, Woo is working to upskill classroom teachers who may specialise in art, rather than algebra, or physical education instead of physics.

“The task of a teacher is not just to know content but how to teach it, and to understand how students learn,” he tells Inquirer.

“I’ll go into a class and teach very differently if I know lots of students want to be engineers or architects, or if they’re interested in getting an apprenticeship as a pastry chef or a carpenter.”

Woo boasts nearly 1.5 million subscribers to his WooTube televised maths lessons on YouTube, which he started to help his own students catch up on lessons if they missed school. He worries that so many students are dropping out of maths in the senior years of high school when mathematics has never been so integral to everyday life. As more students in senior high school shun the STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering and maths), Australia is spiralling into a skills shortage that will hobble its hi-tech economy.

For the first time, the proportion of year 12 students studying the highest level of maths has dropped below 10 per cent. New data from the Australian Mathematical Sciences Institute reveals that year 12 enrolments in intermediate or advanced mathematics have crashed from 34.9 per cent in 2008 to 26.8 per cent in 2020.

AMSI director Tim Marchant describes the collapse in enrolments as an “alarming wake-up call” to reform the teaching of mathematics, which is not mandatory for senior students in the biggest states of Victoria and NSW. “These students are our future workforce,” Marchant says. “Mathematics skills are essential across so many industry sectors and the severity of this situation will impact Australia’s innovation capabilities.”

Engineers Australia chief engineer Jane MacMaster warns the drought of STEM-qualified students is a “ticking time bomb” for Australia’s economy, as industry pivots to hi-tech manufacturing, commerce and agriculture dependent on data and innovation.

“We need to ensure we don’t lose our baseline mathematical capability,” she tells Inquirer. “Clearly the system now is not delivering as good results as we were in the last 10 or 20 years.”

MacMaster points to Australia’s falling performance in global assessment of 15-year-old students’ maths results. The OECD measures the numeracy and science skills of 600,000 teenagers from 79 countries through its Program for International Student Assessment.

The latest exam, involving 14,000 Australian students in 2018, found they had fallen a year behind their achievement in 2013, and 3½ years behind the average Chinese student who sat the test.

“In 2003 we were in the top 10 countries for maths but we’re now 30th,” MacMaster says. “We’re a full year behind where we were 10 years ago.”

MacMaster is concerned that some form of maths study is still not mandatory beyond year 10 in NSW and Victoria, while most universities have scrapped the requirement for high-level maths as a prerequisite for enrolment in medicine, engineering and science subjects.

“I think all school students should study some sort of maths, perhaps with different levels of maths to deal with different abilities and interests,” she says.

“If we’re not making it compulsory for students to study maths at school, there are flow-on effects – students have to catch up in the first year of university.”

NSW has announced plans to make maths compulsory next year or in 2024, with a wider range of maths subjects to suit students’ ability and interests. NSW Education Minister Sarah Mitchell is planning a child-friendly campaign to study mathematics in the next month.

Federal, state and territory education ministers recently agreed to simplify the maths curriculum from primary school to year 10 to focus more on foundational maths knowledge, with less emphasis on theoretical problem-solving. The new syllabus has yet to be released publicly.

MacMaster finds it “really alarming” that up to 40 per cent of maths teachers are not qualified to teach in the field – despite spending four years at university studying to be a teacher.

“PE teachers are being pulled in to design and technology classrooms, and that’s not right,” she says. “Anyone who may teach maths or is appointed to a maths teaching role needs to be qualified in maths.”

Australian Association of Mathematics Teachers chief executive Allan Dougan wants more mid-career professionals in science to retrain as classroom teachers.

“Almost half of the lessons are delivered by someone who’s not qualified to do so,” he told Inquirer. “There are lots of teachers teaching maths who are not trained, and they need support, and to be upskilled.

“We struggle to attract the candidates we need who have undergraduate degrees in mathematics to come into the profession and train as secondary mathematics teachers.

“Many of those graduates are being offered significantly more money to work in science, engineering, accounting and finance than in teaching.”

First-year teachers earn about $73,000 a year – on par with doctors and engineers – but salaries hit a ceiling of about $115,000 for experienced classroom teachers, while tertiary qualified mathematicians can earn twice as much in industry.

One problem is that state and territory governments raised the threshold for mathematicians to retrain as teachers: previously they had to study education for just one year after completing an undergraduate degree in maths or science but now they have to study for two years before teaching in a classroom. Many university students skilled at maths would sooner work as doctors or engineers if they have to spend five years studying for a degree.

Financial incentives – be it through bonus pay rates or lower tertiary study fees for maths teachers – are being recommended as a way of attracting and retaining professionals who can inspire the next generation of engineers, data analysts and biomedical scientists.

Centre for Independent Studies education analyst Glenn Fahey says maths and teachers should be paid 5 per cent more than other teachers, to reflect demand for their skills.

“It makes no sense that maths teachers today are paid the same salary as teachers that come from other disciplines that don’t have the same competitive demands in the marketplace,” he tells Inquirer. “Workers that are in the highest demand get the highest salaries, and teaching should be no exception.”

MacMaster fears students lose interest in maths in primary school, and she wants to “ignite the curiosity and passion and excitement of maths at a young age”.

“Girls and boys want to do something that makes the world a better place,” she says. “Engineering is about delivering practical solutions to problems the world is facing. Young people see climate change as the highest priority challenge facing the world, and we need engineers to help solve that.”

Some primary schools are using a career counselling service to get students interested in the so-called careers of the future, which involve data analysis, artificial intelligence and robotics. Young kids can go online for “virtual work experience” in fields such as digital design, marine biology and commodities training.

Samantha Devlin, chief executive of The Careers Department program, says many young children “rule out technology because they don’t know the jobs that exist”.

“They don’t understand that technology is beyond just coding,” she says.

Woo, who was honoured as a Local Hero in the Australian of the Year Awards in 2018 for his services to teaching, now leads a team of NSW Education Department trainers who are embedded in schools to improve the skills of existing teachers. Yet he still teaches maths and computing at Cherrybrook Technology High School, a public high school in Sydney’s northwest, where he enjoys inspiring all students to see the magic in mathematics.

“Maths is not just about arithmetic and crunching numbers, just as spelling and grammar is not equal to writing,” he says. “It’s about understanding patterns and interpreting our world. Maths is empowering.”