COVID-19: The whole world catches on

As the developed world finally wakes up to the spread of COVID-19, the new weirdness of life in Beijing offers a hint of what may be in store for us.

It was a strange experience being in Beijing this week as much of the developed world finally woke up to the spread of coronavirus COVID-19.

Outbreaks in Italy — where more than 650 cases have been confirmed and 17 people have died — and the admission by US health officials that the spread of COVID-19 in the world’s biggest economy is inevitable, focused minds on the deadly virus first confirmed in China in December, nine weeks ago.

“Unless it’s close to home, people don’t think it’s real,” says former Health Department secretary Jane Halton, who helped co-ordinate Australia’s response to the SARS coronavirus and is now the chairwoman of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, a not-for-profit organisation leading the global effort to find a vaccine for COVID-19.

Many in the world’s equities markets were slow to appreciate the global impact of the virus. Only last week, Australian billionaire investor Hamish Douglass — whose Magellan investment company owns stakes in Chinese online platform Alibaba and the China-enmeshed US tech giant Apple — was downplaying the financial and economic implications of COVID-19. “The coronavirus is largely a short-term economic impact that won’t have longer-term ramifications,’’ Douglass told The Australian.

Markets a mess

Other were less insouciant this week. The world’s largest fund manager, Larry Fink — who sits quite a few rungs above Douglass in the masters of the universe pecking order — said the spread of COVID-19 was far more significant.

Fink, the chief executive of BlackRock, thinks it will reinforce the decoupling of the US economy from China, which the Trump administration has already begun.

“I was surprised that the markets were so stable in front of the whole uncertainty around the coronavirus,” Fink said this week during a trip to Australia.

You don’t need to be Alan Kohler to know that, right around the world, markets aren’t stable any more. Wall Street’s main indexes, the S&P 500 and Nasdaq, fell more than 10 per cent over the week. It was the same grisly story on equity markets across Asia and Europe. In Australia, the S&P/ASX200 closed the week down 9.8 per cent, with $211bn wiped from the bourse.

It is the biggest weekly fall since the height of the global financial crisis, in October 2008.

Disquiet crept into Canberra, too, as Josh Frydenberg admitted that the almost total economic shutdown of Australia’s biggest trading partner would reduce the federal budget bottom line.

“It will have an impact — the question is at what time will it have an impact,” says Martin Parkinson, a former Treasury secretary and, until last year, head of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet.

The tax loss could be spread over the 2019-20 and 2020-21 budget years, which might just save the government’s surplus promise, the centrepiece of its economic agenda.

“It’s not out of the question they scrape it in this year,” Parkinson tells Inquirer.

“It will depend on whether the short-term impact of higher iron ore prices offsets any volume falls and if together they offset the short-term profit, wage and GST loss.’’

Analysis by Deloitte Access Economics out this week estimates that COVID-19 could hit the Australian economy by as much as $5.5bn in the first half of 2020, significant but far from catastrophic in a $2 trillion economy.

“It’s the hit to confidence that we’re watching most closely of all,” writes the firm’s Pradeep Philip and Kristian Kolding.

Halton, previously also the Finance Department’s secretary, tells Inquirer the policy responses to the coronavirus, and the “fear factor” that it might stoke, could cause profound disruptions to the global economy.

“It changes the way people behave, it changes their consumer behaviour, it changes whether they go to cafes, it changes even whether they can go to their workplace,’’ says Halton, who sits on the boards of ANZ and Crown Resorts.

“That fundamentally changes the nature of how the economy is going to work. This has the capacity to tip the whole world economy into global recession. It will depend on how well governments respond.”

Semantics

Some of the week’s panic was linked to semantics — whether COVID-19 was an epidemic with international characteristics or a full-blown pandemic. A pandemic is when an illness spreads at significant scale across numerous countries.

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the World Health Organisation, certainly wasn’t closing the door on that reclassification: “Does this virus have pandemic potential? Absolutely it has. Are we there yet? From our assessment, not yet.”

A few days later, Scott Morrison was less equivocal. “We’re effectively operating now on the basis that there is one,” the Prime Minister said.

With more than 2300 confirmed cases in South Korea, an alarming spread throughout the Middle East and cases now confirmed in more than 50 countries — many with poor healthcare systems — there are plenty of reasons to put Australia on a pandemic footing ahead of a change in definition by the WHO. It is not for nothing that officials on the International Olympic Committee have said it may be necessary to cancel the Tokyo Olympic Games, due to start on July 24.

It would be the first time the Olympics have been cancelled since World World II.

“This is the new war and you have to face it,” said Dick Pound, a longtime IOC member, adding the situation should be reviewed at the end of May. “In and around that time, I’d say folks are going to have to ask: ‘Is this under sufficient control that we can be confident about going to Tokyo, or not?’ ”

Third World dread

Time will tell just how much worse COVID-19 ends up being, both for the health of the world’s population and the global economy.

Three key things will determine its effects, explains Halton, who has been speaking to the government and corporate sector on the fast-spreading coronavirus.

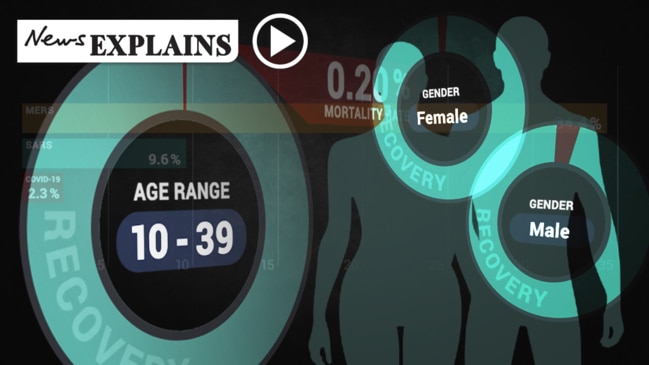

“It’s the attack rate: how many people get it. It’s the death rate and the related severe illness rate. And it’s how many intensive-care beds do you have?”

Ultimately, this means that for all the unease in the developed world this week, it will be poorer countries that are most at risk. It is possible that COVID-19’s death rate, which infectious diseases specialists believe to be about 1 per cent among confirmed cases outside Hubei, could be higher in less-well-equipped countries.

In Beijing, as across much of the world’s most populous countries, life remains abnormal. However, with restrictions in their second month, most are resigned to them — although there are still surprises. After entering with a surgical mask, having my temperature checked and my phone number and passport details recorded, I was allowed to meet my fellow diners at the sparsely populated Beijing restaurant One Thousand and One Nights on Thursday evening.

But staff at the Middle Eastern restaurant, a place with few frills beyond the overwrought gilded ceilings, made sure I didn’t sit with them.

“We’re only allowed two at a table,” one of my four fellow diners explained as I was ushered to a table about 10m from the other end of my group. The five of us were spread across three tables, each with a gap of about half a metre. It’s not a seating arrangement from which great communal dinners are made. No wonder most of the restaurants in China’s capital are still closed.

Tightened dining restrictions seem to be related to a cluster of new coronavirus outbreaks in China’s capital that President Xi Jinping hopes will soon host the National People’s Congress, the country’s signature political event that was officially postponed this week to a date to be determined.

Getting used to ‘weird’

Life in the CBD of this city of 20 million people remains similarly weird. “At my office, we’re only allowed four people in an elevator,” explains one of my dinner companions.

He shows me a photograph of a lift divided with masking tape into four sections. Only one person is allowed per square. And don’t try walking 15m from your desk to a shared office bathroom without a mask on. “Someone reported me for that yesterday,” he adds.

Things are significantly more grim outside the capital. More than 50 million people are still quarantined in the central province of Hubei. Almost half of China’s 770 million-odd workforce — including hundreds of millions of migrant workers — are still to return after the Lunar New Year break.

Many are terrified of becoming the latest confirmed Chinese case of COVID-19, which at more than 78,000 makes up more than 95 per cent of the world’s total reported cases and an even higher proportion of the world’s more than 2800 deaths.

The terror is not new. Life has been this way in China since Wuhan was turned into the world’s biggest-ever quarantine experiment on January 23.

But as of this week it seems that many people around the world have also realised COVID-19 could soon be upsetting more than just dinner plans.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout