Cost-of-living squeeze is prime time for Labor to make bold competition policy moves

This is Labor’s low-risk, consumer-friendly reform road – up to the point where it runs into the sharp elbows of the tech titans, supermarkets, banks, brewers and the Spirit of Australia.

The Greens, with support from the Nationals, want new divestiture powers allowing the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission to seek court orders to force companies in energy, banking and retail to sell assets if they abuse their market power to inflate prices, exploit supply chains or keep out competition.

“Consumers, farmers and workers are at breaking point, Greens senator Nick McKim said while introducing a divestiture bill this week. The Greens want to “smash the supermarket duopoly”.

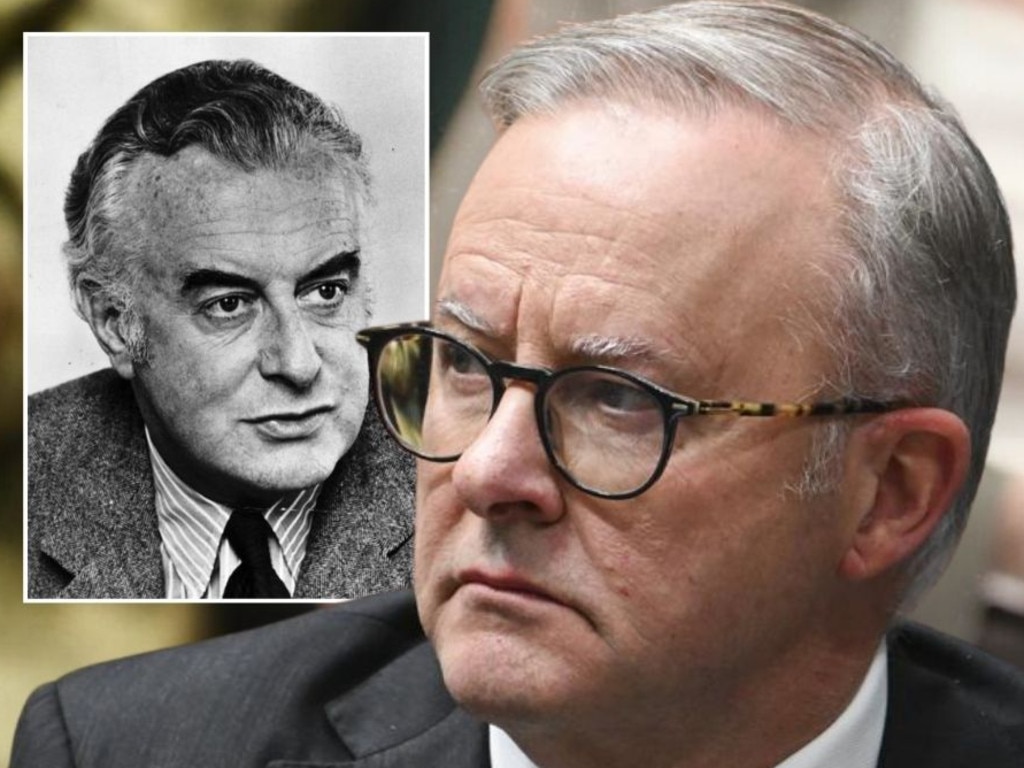

Labor opposes divestiture, which Anthony Albanese labelled an approach you might see in the old Soviet Union. Writing in our pages this week, Business Council chief executive Bran Black described the approach as “extremist” and argued it would cause a plunge in jobs and investment.

Former Labor minister Craig Emerson is reviewing the voluntary Food and Grocery Code of Conduct, which is meant to keep the big two, Aldi, and Metcash on the straight and narrow in dealings with suppliers; an interim report is expected in April. But it’s the year-long supermarkets inquiry by the ACCC that will, with the watchdog’s compulsory information gathering powers, break open the black box on pricing and profits.

Coles and Woolworths can defend themselves; their chiefs, prepped and pepped, will soon be fronting McKim’s supermarket inquiry. Profits here are chunky, but the giants’ after-tax margins are not way out of kilter with the retail industry, here or overseas.

Australians enjoy an amenity from these merchants. For 98 per cent of a population with a continent to itself, there’s vast choice, year-round supply and near ubiquity of product wherever you roam. It’s akin to horizontal retail equalisation. But, as the former Member for Cook (Scott Morrison) once said of the big banks when he slugged them with a new tax, “no one likes you”.

If you’re looking for dominance this Easter long weekend, go to the pub, fridge or Esky. Carlton & United Breweries and Lion, both Japanese owned, hold 85 per cent of the beer market. A parliamentary committee found margins of 40 per cent “may indicate excessive market power” and, no kidding, “would contribute to the high cost of beer for consumers”.

McKim’s assaults on capitalism sound like a tutor in first-year politics; he’s getting traction among young voters confronted with their first episode of “cozzie livs”, due to hikes in the cost of food, energy and housing. The failings of corporates such as Qantas and Optus also bring home the very limited choices in some markets.

The Tasmanian Green should broaden his attention. Gen Z and millennials probably have the most exposure to digital platforms; they are, of course, the product for these oligopolies that, pretty much, wield far more cultural and economic power and do as they please to businesses such as the one that produces this newspaper.

Amid a cost-of-living squeeze, the politics of blame are easy. But it’s a prime opportunity for the Albanese government to make bold policy moves where theory and timing are in accord: competition policy is the killer app to lower household costs, revive the nation’s dire productivity growth and raise material living standards.

Jim Chalmers caught the vibe early in his tenure; the Treasurer and his department are alive in this space, with a rolling review run by its Competition Taskforce and a modern approach to data to get a clearer picture of the play. It’s looking at mergers and developing a whole-of-economy approach to tracking deals, allowing officials and researchers to examine the impact of takeovers on wages, productivity and market share.

ACCC chair Gina Cass-Gottlieb is calling for a new merger regime, in line with other major economies, including mandatory notification of mergers above certain thresholds and a requirement to not complete the transaction until approval is granted. Of the 1000 to 1500 mergers each year (with half of those made by the largest 1 per cent of businesses), the watchdog says about 330 are notified to the ACCC under the existing voluntary merger regime.

Cass-Gottlieb says the big plays are in manufacturing, retail, professional services, and health and social services, which are markets that directly impact consumers as they go about their lives.

“Without effective merger control, we are all likely to face higher prices, lower quality, less innovation, less choice and lower productivity across the economy,” the ACCC chair said in February.

As well, Treasury’s taskforce is investigating non-compete clauses and looking at ways to increase competition in domestic aviation. In December, Labor signed up the states and territories to revitalise National Competition Policy and commit to developing an agenda for pro-competitive reforms.

Labor’s point man on all this toil is Assistant Minister for Competition, Charities and Treasury Andrew Leigh. He argues the research shows that in recent decades there are worrying signs the intensity of competition has weakened, with evidence of increased market concentration and mark-ups in several industries, as well as a lack of economic dynamism – a concept often difficult to grasp.

But Treasury official Jason McDonald put it well when he said dynamism is about the “elasticity of the economy”. “Whether it’s subject to shocks, how well it responds, how quickly it shifts resources to new opportunities, and how quickly wages rise because more productive workers move to more productive firms,” McDonald told parliament in September. “I think you don’t get that without competition, so the words are quite synonymous.”

Leigh tells Inquirer Australia is at a crossroads. “This really is the moment to pursue competition reform,” he says, given the improved data, tools and theory guiding the process. Leigh says competition is about fairness and squarely in Labor’s pro-productivity push; it is crucial if we are to make the most of the big shifts around digitalisation, growth in the care economy and the net-zero transformation.

In January last year, Chalmers asked the House of Representatives standing committee on economics to inquire into promoting economic dynamism, competition and business formation. On Wednesday, the committee, chaired by Victorian Labor MP Daniel Mulino, tabled its hefty report, Better Competition, Better Prices.

Among 44 proposals, the report supports the ACCC’s merger notification position for deals above a threshold, as well as the direction Labor is taking on non-compete clauses for workers. It says banks should offer customers mortgages that track the Reserve Bank’s cash rate, while also notifying depositors they are about to miss out on their “bonus” interest rate. As well, it calls for better use of government procurement to help small businesses win contracts.

“If we don’t improve the level of competition and dynamism within our economy, today’s consumers will get a raw deal, while future generations will be far poorer than they might have been,” Mulino declares in the foreword.

Nerdy as it invariably is and must be, this vital area of corporate and market regulation is Labor’s low-risk, consumer-friendly reform road – up to the point where it runs into the sharp elbows of the tech titans, supermarkets, banks, brewers and the Spirit of Australia.

Can Chalmers crash through?

Big business is up to its ears in pricing inquiries, some of which are populist political plays, while others are deep dives to find out why key product markets seem to be failing – delivering poor outcomes for consumers, workers and the country itself. Coles and Woolworths, with their two-thirds market share in groceries and immense buying power at the farm gate, are under scrutiny.