Costly errors by ABC journalists spark staff policy changes

Not even senior management is prepared to endorse the product of some of the ABC’s biggest current affairs programs and journalists.

It’s a matter of conjecture about why, if the ABC is correct, Australians prefer to watch news bulletins less trustworthy than that provided by the public broadcaster. But what we now know is that senior ABC management is no longer prepared to endorse the product of some of the ABC’s most important news and current affairs programs and journalists.

Last Monday, ABC managing director and editor-in-chief David Anderson sent out a note to staff informing them of an update to the organisation’s guidelines on personal use of social media. He said the revision was necessary because “recently there have been a few high-profile defamation cases where public figures have chosen to sue over personal social media posts”.

Anderson said the ABC is “editorially and legally responsible for what it publishes on its broadcast and digital platforms”. But he added: “What is separately created and posted on personal social media accounts is editorially and legally the responsibility of the owner of the accounts.”

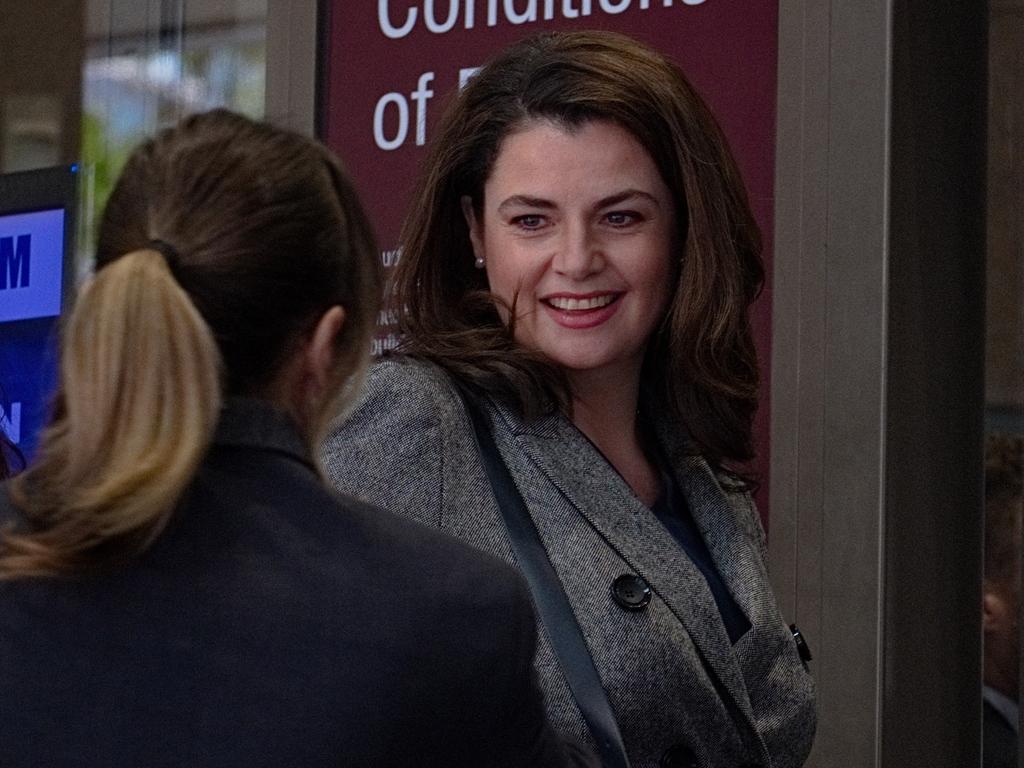

On the same day, ABC Communications released a statement advising that the defamation claim brought against high-profile ABC journalist Louise Milligan by Liberal Party politician Andrew Laming “has been settled”. The statement said this had resolved “a potentially protracted and costly legal action”.

In March, Milligan published several Twitter posts about Laming despite the fact this was not a story she was following for her employer. Milligan subsequently deleted the tweets and on June 17 put out a statement titled “some things that should be known about Dr Andrew Laming”. This did not include an apology for her original error.

Clearly Milligan’s tweets on this issue fell into a personal area which, according to Anderson, is editorially and legally the responsibility of the owner of an account. However, ABC Communications has stated “the ABC decided to pay Ms Milligan’s costs in this matter, a decision arising from particular and exceptional circumstances”.

The ABC, which is a member of the Right to Know Media Coalition, has not explained what the particular and exceptional circumstances are. Therefore, it is not clear as to what kind of precedent this decision amounts to. All we know is that the settlement is not cheap. Legal commentator Chris Merritt told Sky News’s The Bolt Report on Wednesday that the case could have been resolved for $2000 – by a positive response to Laming’s request on May 5 for an apology along with covering his legal costs. It was not forthcoming.

In the end, Laming received a cash payment of $79,000 plus about $50,000 to cover his legal costs. The ABC, despite having an in-house legal department that The Australian’s Sophie Elsworth has estimated has about 28 people, will also pay the external lawyer Bird & Bird for advice. According to Merritt, the total cost to taxpayers is likely to be in the vicinity of $180,000 to $200,000.

No wonder Anderson wants ABC journalists to desist from sounding off on Twitter. According to the ABC, Milligan in this instance made an “honest error”. In which case, she could have apologised immediately. Moreover, no such mistake would have been made if Milligan had checked what she believed were “facts” before embracing Twitter.

In recent times, the credibility of ABC news and current affairs and its journalists has been severely challenged. On May 31, the ABC announced that Coalition minister Christian Porter had decided to discontinue his defamation action against the ABC and Milligan concerning an article by Milligan which was published by ABC Online.

The statement said the ABC stood by its investigative and public-interest journalism. It added that “the ABC did not contend that the serious accusations (about Porter) could be substantiated to the applicable legal standard – criminal or civil”. It also “regretted” that “some readers misinterpreted the article as an accusation of guilt against Mr Porter”, and it paid Porter’s mediation costs, plus its own.

So there you have it. The ABC is willing to put out content that is capable of accusing a person of a serious crime – despite the fact the material does not meet the burden of proof in the criminal (beyond reasonable doubt) or civil (on the balance of probabilities) jurisdiction. It is as unprofessional as that.

This is the test that applies to the living (if they have the finances to take on the taxpayer-funded public broadcaster) and also the dead. Take the recent three-part series Exposed: The Ghost Train Fire documentary for example. It was reported by Caro Meldrum-Hanna and Patrick Begley.

Exposed has been criticised by Troy Bramston in The Australian and former Sydney Morning Herald editor Milton Cockburn in the April-June issue of The Southern Highlands Newsletter. Cockburn put in a complaint to the ABC’s audience and consumer affairs department. Like nearly all complaints lodged with the ABC about the ABC, it was dismissed by the ABC. However, the ABC has announced a review into the program.

Exposed implicated Neville Wran, a long-time serving Labor premier of NSW, in the 1979 ghost train fire at Luna Park in Sydney that killed one man (a parent) and six boys. A most serious charge against a deceased person without legal redress. This fire has been previously investigated, and Exposed produced no compelling evidence against Wran. This documentary was raised with Anderson by Labor senator Tony Sheldon in Senate estimates on May 26. Anderson said Exposed’s case against Wran “presented allegations, not proven facts”. According to Anderson, it is OK for the ABC to make allegations, in the absence of proven facts, in what is presented as a documentary.

In other words, “Australia’s most trusted news service” produces nonfiction material that has not been fact-checked, that satisfies no known legal standard of proof and that presents allegations rather than proven facts in historical documentaries.

No wonder Anderson fears more litigation.

Gerard Henderson is executive director of the Sydney Institute.

ABC management, along with many of its journalists, proclaims the ABC is Australia’s most trusted news source. This despite the fact, on the main evening TV news bulletins, the ABC regularly comes in third behind Channel 7 and Channel 9.