Cost of a healing touch

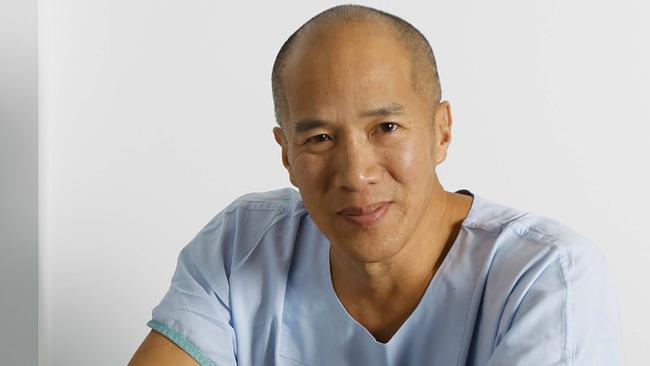

Charlie Teo is at the centre of a debate about the price of his skills.

Of all the technical, blunt and confusing words uttered by doctors, variations of the same short sentence prove the most devastating: “We did all we could.”

This is medicine having the final say, and, if accepted, leaves those most affected to utter only tender goodbyes.

That same short sentence underpins the motivation of everyone confronted with a diagnosis that might be terminal, none more so than parents of sick children. Do all you can to beat it. Find the best doctors, find the best treatments, do whatever it takes. Borrow money, mortgage the house, fundraise, quit your job, whatever.

If you can’t beat it, squeeze whatever life you can out of whatever time you have left. Make sure that when the end comes, you can say to yourself, and your loved ones, that you did all you could.

If it is a brain surgeon you need in such an awful time, the name most Australians think of is Charlie Teo. Google him and you’ll find his speeches, the book he wrote and the books written about him, his teaching, charitable foundations, television appearances and stories about how he did more than any other surgeon to help.

Teo looms large, heroic sometimes to God-like proportions.

In recent years, up to 113 GoFundMe campaigns have been launched to raise money for patients who, in a time of desperation, have faith in Teo to see them through (there do not appear to be any other neurosurgeons named). They include the family of Perth 12-year-old Amelia Lucas, who had a bleak outlook before she underwent surgery last week, and the family of Jed McDonald, 19, whom Teo unfortunately could not save and who died on Monday.

Jed’s mother, Louise, says: “Charlie gave it to us straight and he gave it a shot.

“There is a feeling — I’m sure among all sufferers — that if you don’t go to him you have not done everything possible, and that’s how we felt.”

Teo is confident, passionate and frank. Still something of an outsider in the profession, the 61-year-old has made that one of his selling points: he does things that no other brain surgeon would or could do.

A bio on one of his websites says: “Charlie Teo is not your typical neurosurgeon. In demand across all continents for his willingness to offer surgery to those who have been given no hope, he has appointments in Australia, the USA, India, Vietnam and Singapore.”

Another describes him as “truly a global neurosurgeon”. One bio describes his many achievements and concludes that “as a result of this and much more, Prof Teo has been named the Most Trusted Person in Australia for the last 6 consecutive years”.

Two years ago, this newspaper made Teo a candidate for its Australian of the Year awards.

Changing health sector

But in the years that Teo has been building this reputation, and a niche market unlike anything else in medicine, the health sector in which he operates has been changing. Patients are demanding more information, more transparency over outcomes and costs, greater clarity over ethics and accountability. They are also increasingly searching for the answers online: alongside Teo’s profiles and countless positive media reports, there are now also other doctors talking about best practice and what to expect from your surgeon. The GoFundMe campaigns for the first time put a price on Teo’s work: in some cases $120,000 out of pocket for uninsured patients, or about $60,000 with insurance — well above his peers, even if some report that follow-up operations were free.

When University of Sydney professor and urological surgeon Henry Woo recently tweeted about the “really disturbing” trend of people fundraising to afford Teo’s services, which if they had merit could and should be performed in the public sector, his medical followers agreed. There was no criticism of the patients, their families or donors, who were doing all they could to save a life. This trend seemed to be a symptom of a much bigger problem, or problems, in the system.

Teo felt he was being attacked. Despite years of media reporting of out-of-pocket costs, including in the recent federal election campaign, and efforts to rein in costs, Teo regarded the focus on him to be “scathing and vilifying”. Families in the process of seeing him were justifiably distressed and his supporters were quick to defend the neurosurgeon.

It came down to one question: Is Teo worth the money?

“Am I as good as people say I am? If you speak to any neurosurgeon in Australia they will say it’s all rubbish … so why is it that I am lauded and seduced overseas by the best hospitals?” Teo tells The Australian.

“Surely there is something to that.”

Power imbalance

At present, doctors can charge what they like, or whatever the market will allow. As one veteran doctor pointed out in a message supporting Teo: “What a doctor charges is between the patient & the doctor, full stop.”

But there is an obvious power imbalance there, not to mention the vulnerability, so how would a patient know? What price on saving a life? Medicare and insurers are known to have challenged Teo’s bills in the past.

In March, the federal government announced a new website to help patients and their referring GPs consider and compare the likely costs charged by specialists like Teo.

From next year, they will have access to de-identified historical data on the range of fees being charged for procedures locally. An education program will clarify that high fees do not automatically equate to high quality. The government will then negotiate for specialists to add their own, current, fees to the website.

This week, Chief Medical Officer Brendan Murphy raised the stakes, vowing to investigate whether there is a threshold at which billing becomes so unethical it should be considered malpractice.

Murphy, who conducted a review of out-of-pocket costs for the government, says he is concerned people are having to raise funds to pay for treatment that is available without charge in the public system.

He says pensioners taking out reverse mortgages and people raiding their superannuation, to cover of more than $10,000, are other indicators of a problem.

Without better data, however, GPs will be left to guide patients on considerations of quality. The government will run an education program to help.

Teo’s defence

It was Teo who first raised the idea that his standing came from taking on cases that other surgeons would not, and achieving better results.

He accepted, however, that without publicly available data on the outcomes of his surgery, he could not prove he was great, any more than his critics could prove he was terrible.

According to Teo, the private sector puts a heavy price on his work, which sometimes patients have to bear (he has yet to clarify how in several interviews he came to double the hospital component of a $120,000 bill).

He continues to argue that public hospitals, and his peers, are too proud to let him operate anywhere else and save patients the costs.

John Quinn from the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons says the procedures undertaken by Teo are available in the public sector at no charge, or for less at other private hospitals. He has seen no evidence that Teo does them better or worse.

Others say that without Teo, patients would be forced to go overseas for treatment. Some patients already do.

Indeed, in some cases, the federal government supports their decision and gives financial support, but not where the same procedures are already being done locally.

If Teo is worth whatever he makes from each patient, using procedures available elsewhere, the only way he can justify it is by revealing his superior results. Sharing clinical outcomes even privately with his peers could help lift standards across the board, but it is yet to happen.

Profession’s obligations

Neurosurgical Society of Australasia president Sarah Olson says the profession has an obligation to offer patients options “based on the best medical evidence available with the aim of providing the highest possibility of extended quality of life”.

“There is no medical evidence that those who undergo surgery for many tumours in place of other lower-risk treatment options have better quality of life or increased life expectancy, regardless of the amount of money they spend,” Olson says.

As it stands, Teo saying he has performed 11,000 surgeries isn’t evidence of a success rate, and it would be wrong to think that outcomes aren’t that important if his patients would have died anyway.

Peer review processes

Other neurosurgeons participate in peer review processes (the society compels members to engage in audits as part of their continuing professional development) but not involving Teo.

“Clinical audit by peers is an incredibly important part of being a surgeon,” Olson says.

“It is designed to ultimately improve patient care and outcomes.”

A common theme among Teo’s supporters is that he gives patients hope. His critics suggest it is false hope.

False hope, at significant cost, be it to family finances or remaining quality of life, would certainly require more transparency and accountability.

“We feel it is important that patients in a vulnerable position have the information they need to make informed choices about their treatment options,” Olson says. “Surgery is not always the best choice.”

In this complex, nuanced debate, another element may have been overlooked.

Many people die of brain tumours without having seen Teo, and the bereaved might wonder if things could have been different at the hands of the global neurosurgeon and most trusted person in Australia.

Teo shines so brightly, the mainstream health system seems to be under a cloud.

It is one thing for families to take some comfort in the belief they did all they could, it is another thing to be left with painful regret, whatever the circumstances.

The debate about costs, ethics, clinical decision-making and transparency of outcomes should lead to restoring confidence in the system.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout