Corruption exposed at the heart of the Vatican goes unpunished

It has been described as the Vatican’s worst corruption scandal since the Italian banker Roberto Calvi was found hanged from Blackfriars Bridge in 1982. But seven months after the ‘trial of the century’, not one official has seen the inside of a Holy See prison cell.

It could not have been more dramatic if it had been written for Netflix: a special courtroom set up in the same building as the Sistine Chapel, a leading judge who spent a lifetime putting Mafia bosses behind bars and a Sardinian cardinal – once a papal contender himself – accused of embezzlement and bringing “merchants to the temple”.

And yet nearly seven months after the denouement of the Pope’s so-called Vatican trial of the century, not one of the 10 officials accused of an array of financial crimes – from abuse of office to money laundering – has seen the inside of a Holy See prison cell.

Chief Judge Giuseppe Pignatone and a panel of senior Italian judicial colleagues found nine of the accused guilty last December. Prison sentences totalling 38 years were handed down to six officials along with hundreds of thousands of euros in fines.

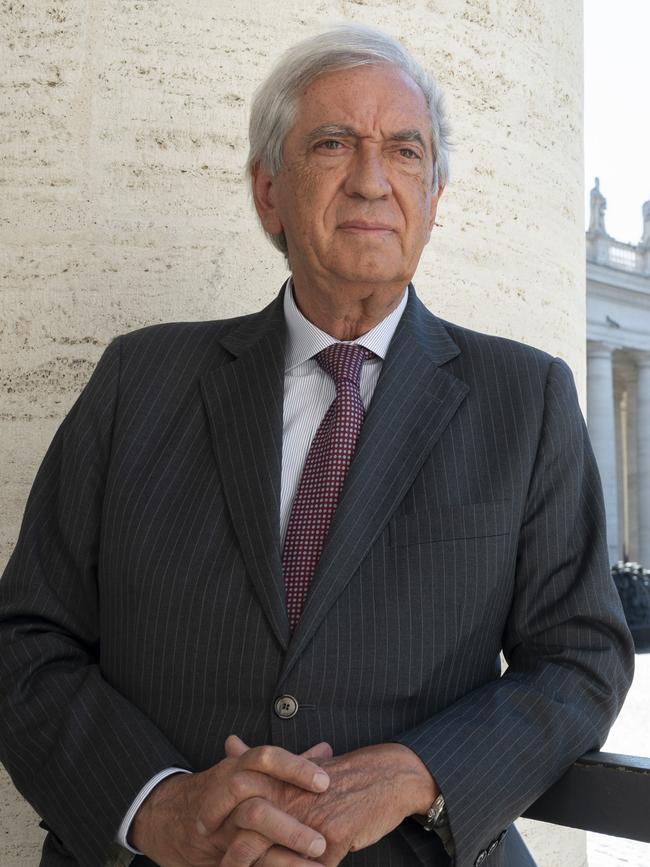

Cardinal Angelo Becciu, former deputy of the Secretariat of State – and arch nemesis of the late Cardinal George Pell – was sentenced to five and a half years on three counts of embezzlement, fined €8000 and given a lifetime ban from holding any form of public office.

Legal observers agree, however, that it is unlikely those facing prison sentences will end up behind bars any time soon, if at all. The Vatican is an independent, sovereign nation-state with its own legal system but its incarceration procedures mirror those of Italy and those awaiting appeal are allowed to remain free unless deemed violent or a flight risk. As the majority of those convicted have signalled they will seek legal redress, hearings could realistically not begin before the end of the year, taking at least another 12 months to conclude.

The initial investigation began in 2018 when the Vatican bought a former Harrod’s storeroom on London’s Sloane Avenue from an Italian financier, Raffaele Mincione. It piqued immediate interest in the Holy See Audit Office and a loan request was reported as “irregular” by Jean Baptiste De Franssu, president of the Vatican Bank himself.

From there, the prosecutor assigned to the case, Alessandro Diddi, found himself mired in a growing labyrinth of byzantine deals and middlemen, murky loans and foreign bank accounts. His case expanded rapidly, leading to allegations of abuse of office, embezzlement and conspiracy by multiple people – all of them connected to the Holy See in one way or another.

But six years later, the Vatican has once again shown itself to be a place as Kafkaesque and unpredictable as it is sacred, and while we may now know the names and roles played by the cast in the corruption saga, we do not yet know when, or how, the story will really end.

For Cardinal Becciu, the first cardinal to be convicted of a crime by a lay court in Holy See history, it appears that life has not changed one iota.

While his legal team plans an appeal strategy, Becciu, it is said, remains ensconced in his luxury, grace-and-favour apartment on the top floor of the Palazzo del Santo Uffizio, right next door to St Peter’s Square. The Pope appears to have allowed Becciu, the only Vatican citizen among the accused, to stay in his palatial digs despite sacking him abruptly in 2020 and banning him from entering the conclave that will choose the next Pope after Francis’s resignation or death.

The Becciu residence, believed to be the largest available in Vatican City, was renovated in 2019 not long after he was made cardinal. It includes quarters for the sisters who clean and cook for him and has a kitchen described as restaurant grade. It is the very same apartment, according to evidence presented at the trial, where Cecilia Marogna – a self-described “security consultant” – enjoyed overnight stays.

How do we know this? Because Diddi’s investigators found that Marogna, now 43 and born on the island of Sardinia like her friend the Cardinal, posted pictures of herself in his flat and unabashedly captioned them “my paradise” on her Facebook page.

Dubbed La Dama Bianca (The White Dame) by the Italian media, Marogna was charged with misappropriation of $US70,000 in Vatican funds, apparently used to stay in luxury hotels and buy high-end fashion including handbags. The money was diverted from a total pot of $US600,000 which had been set aside to pay ransom for a Colombian nun kidnapped by Islamic militants in Mali in 2017.

The tribunal sentenced Marogna to three years and nine months and placed her on a ban from public office. She too is believed be planning an appeal.

Becciu’s apartment is also the place he secretly taped a telephone conversation with Francis himself. It was July 24, 2021, just three days before the Vatican trial began and Becciu, clearly under pressure, wanted Francis to confirm that he had personally authorised the ransom funds and their payment, by Marogna, to a British security firm hired to manage the logistics of the nun’s return from her captors.

Prosecutors asked journalists to leave the tribunal when the recording, made by Becciu’s niece, was played in court. However, a written transcript was leaked not long after, serving only to show that the Pope listened to Becciu, acknowledged a vague memory of the ransom issue and asked the Cardinal to put his request in writing.

Just this week, Becciu took the extraordinary step of protesting his innocence publicly: a disgraced Cardinal who offered himself for a sit-down “exclusive” interview with the Italian national newspaper Corriere Della Sera. The interviewer did not hold back. Asked about his secret bugging of the Pontiff, Becciu claimed it was an act born of his “dramatic desperation as an innocent accused”. He had been treated like a leper, he said, and could no longer “stay silent in the face of injustice”.

“It hurts me to be portrayed as a Cardinal profiteer/businessman … not a cent has gone into my pockets. They hoped I would retire to Sardinia without a fight, but I will not. I will shout my innocence to the world with the force of truth behind me.

“The Bible says one should not allow the sun to set without doing justice for the poor defrauded. It was considered a sin that cried out for vengeance before God. For almost four years I have been defrauded of my honour, my episcopal ministry and my serenity. It is much more than a sunset.”

Meanwhile, Raffaele Mincione, the Italian financier at the centre of the ill-fated €350m London property deal that sparked the trial, also remains free after lodging – and winning – an unprecedented request to have his case heard in the English High Court.

Mincione, like Becciu, was sentenced to five and half years’ jail but he filed his suit in 2020 when he was still under investigation and a good two years before his conviction. He argued then that both the Vatican inquiry and the trial itself are illegal under international law and breached his human rights.

Mincione had managed hundreds of millions of euros in Vatican funds from 2013 until 2018 when the relationship was severed over the London property deal. The Holy See had originally invested in a 45 per cent stake in the Sloane Avenue block in 2014, only buying it out entirely via the businessman four years later. According to the Vatican lawyers, Mincione claimed the building’s market value at point of sale to be £275m. In the end, the Holy See ended up forfeiting the balance of its investment with the financier to secure total ownership as well as paying millions in penalties for its early withdrawal from the deal.

The building was later sold by the Secretariat of State to the Boston-based private investment firm Bain Capital at a loss of more than €100m euros.

Last week, during the first London hearing before Justice Robin Knowles in the High Court, Mincione’s legal team denied their client conspired to inflate the value of the Sloane Avenue building, claiming he acted in “good faith” in all his dealings with the Holy See. The Vatican’s legal team begged to differ, describing the deal as “fraud” and that it had unfolded in a manner “manifestly contrary” to the interests of the Holy See.

And here, too, the story becomes even muddier. According to Mincione, the test of whether he acted in “good faith” requires going back even further to 2012, when he says he was approached by another of the now convicted co-conspirators, Enrico Crasso, who wanted help shepherding another Vatican investment, this time in an Angolan oil company proposed by – yes, you guessed it – Cardinal Becciu.

Mincione told the American Catholic news site The Pillar last year that his company had done due diligence on the Angolan deal but had eventually decided it was financially unworkable and so walked away from Becciu’s oil plan.

The Secretariat of State’s lawyers tell another story. They argue that when Crasso introduced Mincione to the Vatican, he championed the cause for the Angolan project, both personally and via his company. He even set up a fund through which he directed the Vatican investment of $US200m. It was only when the deposit was safely with his company that Mincione’s view changed and he presented the Angolan project as unworkable.

Developments make a little more sense when it was disclosed that the Vatican’s deposit was secured through credit lines from two banks, Credit Suisse and Banca Svizzera Italiana. With loans requiring servicing at high interest rates, the need to invest after the “collapse” of the Angolan project suddenly became rather more compelling.

It was at this point, say the Secretariat’s lawyers, that Mincione offered the Vatican the “opportunity” to invest in his London property. It is interesting to note here that when Ed Condon, a canon lawyer who was then the Catholic News Agency’s Washington DC correspondent, revealed that the London property deal had been financed via high-interest loans to the Vatican, his scoop article was ferociously denied as “shameful, false and misleading” by none other than Cardinal Angelo Becciu.

Legal observers suggest that Mincione’s lawsuit in the UK will be seen as a potential test case in which an external jurisdiction, in this case a British court, will have to respond to claims that the Holy See used unfair means to test claims of corruption. In other words, it will either give the Vatican trial an international vote of confidence – or not.

During the past few months, lawyers for the various accused have made much of the Pope’s decision to pass special decrees, known as “rescritti”, which authorised phone tapping, email interception and immediate arrests during the investigation process. Described widely as “changes to the law” which allegedly denied defendants’ rights to fair process, the claims have been repeated both by Mincione and Cardinal Becciu’s legal team, and a raft of Italian media sympathetic to their cause.

However, according to Condon, now editor and co-founder of The Pillar, a highly respected Catholic news agency, this is technically incorrect. The four rescritti issued by Francis, he says, are legal instruments, acts of executive not legislative power. Thus, they do not change the law but simply allow for flexibility in individual cases.

Arguments that they gave investigators carte blanche to operate without judicial oversight are not accurate because the papal executive orders simply allowed the inquiry to begin and then dispensed it from one procedural reporting law.

“Francis essentially told investigators they did not have to report on their progress to the people they were investigating” he said.

The “trial of the century” was supposed to be the triumphant culmination of Francis’s campaign to show that under his watch, there would be a new regime of official scrutiny of what George Pell described as the “murky” work of Holy See finances.

Its by-product would hopefully reinvigorate stymied financial reforms, at last pushing the Holy See into 21st century accounting rules and modern, global audit mechanisms and oversight.

It’s fair to say, however, that the proceedings have also served to uncover a litany of continuing embarrassments, highlighting an ingrained and continuing culture of self interest and institutional secrecy among some in the highest echelons of the Roman curia.

On Wednesday, Libero Milone, the first Vatican auditor-general appointed by the Pope himself and sacked for “spying” on the orders of Cardinal Becciu, was forced to lodge an appeal after his wrongful dismissal lawsuit brought with his deputy, the late Ferruccio Panicco, was rejected by a Vatican court.

Milone, a former Deloittes chairman, and Panicco, a forensic accountant, had worked side by side with Pell and had been the first to flag and seek – unsuccessfully – full documentation on the London property deal, signalling a litany of other questionable or inappropriate Vatican deals, including in pharmaceutical companies that manufacture the abortion pill.

The two men fought for years to uncover the reasons for their dismissal and reach an out-of-court settlement but were stonewalled at every turn, finally lodging a €9m compensation claim for reputational damage and lost earnings in 2022.

Milone has often said that he took the job in retirement to give something back to the church and wanted only to work towards – and help build – a financial system of oversight that would safeguard the millions in hard-earned donations made by the Catholic faithful all over the world.

And it is here, with Peter’s Pence – the annual collection that supports the charitable works of the Catholic Church and which historically makes up about a third of the Holy See’s income – that the greatest damage has been done.

Ongoing scandals, from child sexual abuse to financial maladministration, have eroded trust in the Catholic institution, understandably affecting the desire to donate. Last year, there was a slight increase in donations compared with 2022, but in the end, revenue nearly halved and millions of euros worth of real estate assets were sold to cover the costs of the Roman curia.

The scale of the financial crisis was hinted at by the Prefect of the Secretariat of the Economy, Maximino Caballero Ledo, last year when he estimated that the Holy See is facing a structural budget deficit of “between €50m and €60m a year”.

This despite nearly a decade of cost-cutting measures and a pay and curia-wide hiring freeze instituted early on by Francis as part of his financial reforms.

Ed Condon argues that while the slight uptick in Peter’s Pence donations gleaned headlines last year, the stark reality is that there is an ongoing budgetary black hole as the Vatican’s need for cash absorbs not just Peter’s Pence donations but triggers the sale of the fund’s assets as well.

Senior officials close to the Secretariat for the Economy told The Pillar that without a serious change of financial course, a curial cash crunch looks unavoidable, at least in the medium term and potentially within five years: “There is no magic money tree in the Vatican gardens.”

And yet it is understood that in the earliest years of his economic reforms, George Pell’s department had already drawn up proposals which would generate new, reliable, long-term income streams for the Holy See. Projects included a global audit and identification of unused land and buildings and plans to harness long-term external partnerships to redevelop them for industrial, residential, or mixed uses. Leaseholds would stretch out for decades ensuring asset maintenance, solid ongoing security and financial stability.

Pell and his team, sources said, had clearly identified that opportunities for new, long-term revenue generation were there for the picking.

But once again, institutional pushback and the will for change among the old guard and the curia was not.

Paola Totaro is a London-based freelance writer and author.